Ocular Allergy and Contact Lens Wear:

Signs, Symptoms and Solutions

BY DR. JOSEPH P. SHOVLIN, OD, FAAO: MICHAEL BOLAND, BS AND DR.

MICHAEL D. DEPAOLIS, OD

APRIL 1998

There's more to ocular allergy than just itchy eyes. Allergy sufferers need your expertise to enjoy safe, comfortable contact lens wear.

It's inevitable. Most of your contact lens patients will encounter at least one of the many forms of ocular allergy at some point in time. Some reactions are directly related to lens wear; others present as a systemic disease concomitant with lens wear. In our continued quest for safe and comfortable lens wear, we must be equipped to manage these presentations through early recognition of signs and symptoms, a cessation of lens wear and the use of appropriate pharmaceutical agents. Lack of attention to detail and inappropriate treatment can result in significant ocular irritation and increased ocular morbidity.

Patient history is important in determining whether or not the presenting condition is related to contact lens wear. Allergic responses in contact lens wearers can be caused by the lenses (which is rare), by lens deposits, by solutions used or by a concomitant allergy such as hay fever. A history of allergic reaction in general will usually exonerate lenses and solutions as a causative agent. When evaluating an allergy sufferer, be sure to perform: a careful history -- pay special attention to a family history of allergy; patient evaluation -- examine hands, scalp and face; and slit lamp evaluation -- check lower lid (for follicular response, shrinkage of fornices and mucous strands to eliminate other causes for presenting symptoms), upper lid (look for cobblestone papillae of giant papillary conjunctivitis from lens wear and vernal conjunctivitis and "gray" follicles of inclusion conjunctivitis as a differential diagnosis), bulbar conjunctiva (follicles are highly suggestive of chemical sensitivity response and fine separation between the conjunctiva and episcleral areas containing a pink exudate suggests allergic response), and limbus (gelatinous elevations, Trantas' dots and white, powdery infiltrates are indicative of vernal keratoconjunctivitis).

Classifications

Allergic responses can be classified under the Coombs and Gell system (1963), which is somewhat dated and simplistic, yet useful in understanding many allergic conditions. The majority of reactions encountered in contact lens wear fall under Types I and IV, though a given hypersensitivity response may involve more than one type of reaction.

A Type I ocular reaction (anaphylaxis) is the most common, characterized by itching, a watery/mucoid discharge, lid hyperemia, lid edema, conjunctival hyperemia and conjunctival edema, with the response evolving into a papillary reaction and possibly eosinophils. Examples include asthma, hay fever conjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC), vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and drug hypersensitivity. Depending upon the size of the antigen, the reaction can include the secretion of potent vasoactive mediators like histamine, slow-reacting substances of anaphylaxis, eosinophil chemotactic factor and platelet activating factor. Sensitization to the antigen takes seven to 10 days, with the process starting within minutes of re-exposure and generally ending within an hour. Histology shows vasodilation, edema and infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils and mast cells. Fine fibrous strands pass between the lid epithelium and tarsus. As the reaction evolves, clinical papillae, which look like velvety, vascular elevations, develop in the area between the strands and may coalesce into giant papillae (>1.0mm).

A Type II (cytotoxic) reaction is produced by exogenous (microbes) or endogenous (drug) antigens. Examples are drug reactions and reactions that occur in response to transfusions, nephritis, organ transplants and autoimmune disease. IgG and IgM and complement bind to the antigen, which is then phagocytized by macrophages and natural killer cells.

In a Type III (immune complex) hypersensitivity, antigens combine with circulating antibodies to form an insoluble immune complex deposited within vessel walls or in avascular areas like the cornea. Examples are marginal infiltrates, ulcers, viral infections and contact lens related infiltrates.

Type IV responses cause many of the reactions we encounter as a result of contact lens wear. Delayed hypersensitivity is the hallmark of the reaction, and itching is the primary symptom. Other signs include minimal discharge (usually watery), an uncommon cutaneous or lid involvement and absence of an eosinophilic response. Examples of a Type IV reaction include contact allergy and phylctenulosis (a response to microbial antigen). Some contact antigens undergo mitosis, whereby they proliferate and produce lymphokines, which mediate an inflammatory response. Sensitization of the T-lymphocyte probably takes seven to 10 days, and the process starts within 24 hours and generally ends within 72 hours. Histology shows a mononuclear and lymphocytic infiltrate. A few neutrophils and eosinophils are present. Lymphocytes often aggregate into collections of follicles appearing which are most prominent in the lower lateral tarsal conjunctiva.

Other conditions must be distinguished from true allergic responses in contact lens wear. Irritative keratoconjunctivitis has no real antigen. An inciting agent, by its chemical and mechanical properties, irritates the cornea and conjunctiva immediately upon first application. The response is not greater or different between exposures. Symptoms include redness, watery discharge, burning and mild conjunctival edema. Itching is rare. There is no follicular response or lymphadenopathy, but a papillary response is possible with chronic exposure from vascular dilation. Treatment includes removing the offending agent and administering appropriate therapy to the ocular surface.

Solutions and Lens Material Reactions

True allergic responses in contact lens wearers without a history of allergic reactions may rarely be caused by the lens materials themselves or more frequently by solution preservatives, especially those still preserved with thimerosal and EDTA. The most common reaction associated with EDTA is a contact allergy. Lens material or solution reactions can be toxic in nature rather than a true allergic response, easily distinguished by an absence of itching and bulbar follicles and by the immediacy of reaction. Symptoms of an allergic reaction include tearing, burning, discomfort on lens insertion, photophobia, decreased wearing time and itching. Other occurrences include signs of conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis, corneal edema, microcysts, superficial staining, papules, infiltrates and follicles. Treatment entails immediate discontinuation of lens wear, as well as changing the solution and possibly refitting the patient into a different material. Keep in mind that a true allergy to a lens polymer is quite rare. Some patients achieve relief from symptoms of allergy with homeopathic medications, like Similasan #2.

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis

The pathogenesis of giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) can be linked with such antigens as hard, soft and rigid gas permeable lenses, sutures, prostheses and histoacryl glue in contact with the conjunctival epithelium. Evidence suggests that GPC in contact lens wearers is an immunologic response by the lymphoid tissue of the upper lid to allergens embedded within mucus-like deposits on the surface of the lens. The etiology appears likely to be both a basophilic hypersensitivity reaction (Type IV reaction) and a mechanical trauma arising from a lens surface roughened by deposit. Disposable and planned replacement hydrogel regimens have reduced incidence of GPC and other problems associated with a chronic buildup of lens deposits and biofilm.

Symptoms include mucus in the eyes upon awakening and slight itching immediately upon lens removal. Signs include a generalized thickening of the upper lid tarsal conjunctiva with elevation of small papillae and erythema of the tarsal area. A ptosis is possible. If undetected, GPC will cause blurring of vision after hours of lens wear, increased lens awareness and overall lens intolerance. Corneal involvement, though rare, may include punctate epithelial erosion, limbal hypertrophy, filaments and mucous plaque. Treatment varies with the degree of GPC or symptoms. In most cases, an important first step is lens wear discontinuation, which alone may relieve signs and symptoms. Minor cases can be managed by changing solutions and recleaning lenses or by switching to disposable lenses. In more advanced cases, you need to change the material, such as going from a soft lens to a rigid lens. If the patient is wearing a rigid lens, pay special attention to the lens edge design. In the rare case where symptomatology persists after lens removal, a topical steroid may be helpful. More suitable topical medications for GPC are mast cell stabilizers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs), decongestants, antihistamines and combination topical drugs. Pay careful attention to the patient's wearing schedule, lens material, fitting relationship and lens care solutions.

Contact lens wearers who suffer from seasonal allergy like vernal catarrh can pose a diagnostic challenge, although the management is somewhat similar. There are a few clinical features that will aid in a differential diagnosis of GPC whether it's primarily contact lens related or significantly driven by a vernal or atopic response. In vernal catarrh, the papillae tend to be flatter and more hexagonal in shape with distinct, sharp-edged borders (Fig. 1). There's greater itching with vernal responses because there are more mediators being released from mast cells and there's a greater eosinophilic response.

|

Contact lens induced GPC causes more erythema of the tarsal conjunctiva in part due to the mechanical features of the lens. Raised, whitish areas at the tips of the papillae may appear with contact lens induced GPC, but generally not with vernal catarrh. This probably represents fibrotic change or an infiltrative response to inflammation. The creation of new collagen is typically not a feature of mast cell degranulation (Fig. 2). Some differences exist between GPC occurring in rigid versus soft lens wearers. GPC is 10 times more common and usually occurs earlier in soft lens wearers than in rigid lens wearers. The responses are similar, but the etiologies are different (immune vs. mechanical). In soft lens GPC, the response is often more diffuse but tends to be more severe in the zones nearest the fold because these are the zones with the greatest immunologic response. The response is generally greater nasally than temporally (Fig. 3). In rigid lens GPC, the response is often more localized and is found to be greater closer to the lash margin (involves zones two and three) because of the lens diameter and mechanical etiology (Fig. 4). The papillae are smaller with more space found between each one. A crater-like excavation is sometimes present and the response can occasionally be greater on the lower tarsal conjunctiva. High myopic prescriptions may induce a greater and disparate response between eyes, depending upon the edge design and lens material (deposition potential) used.

|

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

Described by Arlt in 1846, VKC is often a severe bilateral disorder that affects children and adolescents, primarily males. Onset is usually around or before the age of 10 (80% of cases are under age 14), but it will generally dissipate by age 40. VKC is a Type I and Type II hypersensitivity reaction that presents as an interstitial inflammation of the conjunctiva. Allergens are not well defined, but tissue biopsy suggests that VKC is an IgE-mediated response with elevated tear histamine levels. VKC occurs more frequently in warmer climates, with symptomatology often beginning in the spring and declining in the fall. Sixty to 70 percent of patients with VKC have a familial history of atopic diseases, and 75 percent of the VKC cases occur in conjunction with asthma, allergic rhinitis or atopic eczema.

Signs and symptoms include itching, conjunctival hyperemia and edema, mucous discharge, (often found in the lower fornix), papillary hypertrophy and some corneal involvement. Two clinical forms of the disease exist: (1) palpebral, which includes giant papillary hypertrophy of the superior tarsal conjunctiva, mild edema and hyperemia of the lower tarsal conjunctiva, many eosinophils and greater corneal involvement; and (2) limbal, which is more common among black people and includes papillary hypertrophy at the superior limbus, and limbal papillae which may enlarge to produce hyperplastic, gelatinous tissue (chalky) in severe responses. Horner's points or Trantas' dots are terms that describe the clinical features of degenerated epithelial cells and eosinophils in deeper epithelial layers. This is a sign that is pathognomonic for the vernal process. VKC patients can have four times the number of mast cells in their tears, as well as increased tear histamine levels.

Corneal involvement in VKC presents in various ways. Punctate epithelial erosion, punctate epithelial keratitis, macro-ulceration, pannus formation, pseudo-gerontoxin and corneal scarring and opacification are all possible. A sterile ulcer is a troubling sign and one that carries a sight-threatening potential. It is generally a shallow, hard-bordered (transverse oval) lesion superior to the visual axis, but can be located anywhere in the cornea even inferiorly (Fig. 5).

|

Management of VKC in its acute form may include antihistamines (topical and oral), mast cell stabilizers, corticosteroids (topical and oral) and NSAIDs. Recommended for significant VKC are initial high doses of topical corticosteroids with a preference for solutions with a rapid taper, as well as low viscosity tear substitutes, cold compresses, acetylcysteine for mucous plaques and filaments and, if possible, removal from the environment that contains offending antigens. The long-term application of mast cell stabilizers may help and minimize or eliminate the need for corticosteroids. Skin testing and desensitization are of no relative value.

Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis

AKC is most likely a Type I and Type II hypersensitivity reaction. AKC differs from hay fever and vernal conjunctivitis in that it presents in individuals with adult atopic eczema, is much more severe and can produce significant corneal complications. Diagnosis is based on familial allergy history, such as hay fever, asthma, childhood eczema, food allergy, urticaria and allergic rhinitis, though AKC may present before the systemic signs of atopy. A chronic persistent dermatitis affecting the face, neck, shoulders, axillae, thorax, popliteal and antecubital areas with exacerbations and remissions over a period of years is characteristic. Performing a clinical examination is usually sufficient to identify AKC. However, a differential diagnosis is often necessary to distinguish AKC from contact blepharo-keratoconjunctivitis, marginal blepharitis and VKC.

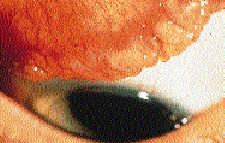

|

Symptoms intensify in the winter months and include itching, burning, mucoid discharge, redness and photophobia. The clinical signs are a milky conjunctiva, papillary hypertrophy, erythema of the lid margins (Fig. 6), scaly/infiltrated lids, crusting between and around the cilia, increased wrinkling of the skin around the eyes and corneal changes (pannus, ulceration, scarring, keratoconus, punctate epithelial keratitis). Cicatrization, giant papules and papillary hyperemia are representative of a chronic state. Cataracts, retinal detachment and perhaps keratoconus are some of the more serious adverse sequelae of long-term AKC. Cataracts are associated with the disease and the use of corticosteroids. Keratoconus and retinal detachment may be a result of vigorous eye rubbing.

Acute episodes are often managed with pulse topical steroids, artificial tears and antihistamines (topical and oral). Chronic AKC management includes the use of mast cell stabilizers and the judicious use of corticosteroids. Secondary bacterial infection may also occur, primarily staphylococcal blepharitis. In these cases, add topical antibiotic therapy to the specific anti-allergic treatment. Interestingly, in the early 1900s, treatment of this condition included injections of purified staph toxins.

Systemic cyclosporine A, which should be commercially available in the not-too-distant future, presents an interesting alternative to oral steroids in severe AKC. Cyclosporine acts by selectively inhibiting the T-lymphocytes. Topical cyclosporine A has been found to be effective in treating the signs and symptoms of corticosteroid dependent or resistant VKC and AKC. Despite these encouraging findings, recurrence of symptoms is generally the rule upon withdrawal of the medication.

Hay Fever Conjunctivitis

Hay fever conjunctivitis presents most often as an acute bilateral conjunctival reaction to airborne antigens in a patient with a history of allergies, and may be accompanied by hay fever symptoms of the nose and throat. This IgE-mediated reaction is generally triggered by tree, weed or grass pollens, molds, dust and animal dander.

Clinical signs are usually subtle or non-evident, but may include dilation of the ciliary vessels and occasionally mild dilation of the superficial or the deep conjunctival vessels. Corneal signs are usually absent (except for a mild staining), and a pale, boggy edema of the inferior tarsal conjunctiva may preclude a hyperemic, edematous presentation. Symptoms include significant itching, burning, photophobia and tearing. Ocular hay fever symptoms, such as nasal symptoms, may be acute. Avoidance of the offending allergens is almost impossible, so prompt therapy with topical vasoconstrictors, antihistamines and corticosteroids when needed often yields relief.

Contact Allergy

Contact allergy can either be an immediate or delayed hypersensitivity to substances that come in contact with the eye or surrounding tissue. Potential sensitizers include common items like cosmetics, hair sprays, nail polish, detergents, after-shave lotions, sunscreens and various household and industrial agents. Common outdoor sensitizers include poison ivy and poison oak. Most contact allergy reactions are iatrogenic, most likely a Type IV hypersensitivity, but the distinction between a Type I drug hypersensitivity and a contact allergy may not be clinically apparent. For example, certain drugs, like anesthetics, atropine-like pharmaceuticals and the antibiotics tobramycin, gentamicin and neomycin induce an immediate hypersensitivity reaction. The result is a watery, itchy, papillary response with prominent eosinophils. A delayed hypersensitivity is more apparent with drugs like thimerosal, epinephrine, dipivefrin, vidarabine and idoxuridine. This reaction is characterized by less itching, little discharge, few eosinophils and follicles. If untreated or exacerbated, contact allergy can exhibit an intensely red conjunctiva, moderate edema, macerated skin of the eyelids and margins, defects on the corneal surface (Fig. 7) and possible conjunctival scarring and corneal thinning (corneal melting in the case of topical drug abuse).

|

A thorough history and examination are crucial. Diagnosing the condition remains difficult since patients often present having used several medications before seeking professional help. If the condition is iatrogenic, eliminating and avoiding the substance is the most effective preventive and therapeutic approach. Complete resolution of the condition may take weeks, even months. Topical corticosteroids remain the mainstay of therapy. Recent difficulty in obtaining dexamethasone ointment has created a need to substitute with corticosteroids not specifically for ocular use. Corneal toxicity is possible, so remember to tell patients to use some caution in applying ointments or creams. Ophthalmic topicals like fluoromethalone (FML ointment) or tobramycin/dexamethasone (Tobradex ointment) are suitable alternatives.

Microbial Allergy

Microbial allergies may be classified as delayed reactions. The antigen can be a bacterial protein from the death or lysis of the organism syphilis or tuberculosis, or it can be a bacterial product (staph toxin). The most commonly found reactions are those associated with phylctenulosis, a specific response to a microbial antigen generally associated with a reaction to tuberculosis or Staphylococcus. If a phlyctenular reaction is associated with gastrointestinal upset, consider an infection from nematodes. Interstitial keratitis is another reaction to a microbial antigen.

Phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis (PKC) is characterized by a raised nodule of lymphocytes (phlyctenule) at the limbus. Incidence may increase slightly during the spring. Phlyctenular conjunctivitis is usually the first and only sign of this disease. It is characterized by a local area of hyperemia, usually near the limbus but may be entirely on the conjunctiva. Nodules can be single or multiple, found on the bulbar or the palpebral conjunctiva and on the lid margin. Phlyctenules, which appear within a day or two in the center of the hyperemic area and quickly elevate to a millimeter or more above the surrounding conjunctiva, are gray or yellow-white and avascular (Fig. 8). After several days, a small dimple may appear at the apex, which then gradually spreads to shrink the nodule. Symptoms in cases limited to the conjunctiva are relatively mild and include itching, tearing, photophobia and irritation. Phlyctenular keratitis has a tendency to break down and form a marginal ulcer, which should not be confused for an infectious process in contact lens wearers. Symptoms are usually more severe and can include blepharospasm. The healing response will leave a scar or fasicular ulcer. A pannus is possible and is the result of diffuse infiltration or recurrent phlyctenules that develop close to the blood vessels and progress centrally. Super-infection is always a concern, so appropriate antibiotic coverage is essential.

|

Differential diagnosis must include acne rosacea, VKC (limbal), nodular episcleritis, and inactive lesions from herpetic keratitis and syphilitic keratitis. Phlyctenules have occurred in Gonococcus infection, moraxella, tularemia, leishmaniasis, brusellosis and helminthiasis along with its two most common causes (tuberculosis and Staphylococcus). Staphylococcal PKC differs from tuberculin PKC in that it is sometimes much more resistant to topical steroids and is not accompanied by severe photophobia. Management includes eliminating the antigen and instilling a short dose of topical corticosteroid. It's a good idea to provide antibiotic coverage for the cornea if a keratitis is present. Avoid trigger mechanisms like blepharitis, acute bacterial conjunctivitis and vitamin deficiencies. If signs and symptoms warrant, a medical work-up should include a PPD and perhaps a chest film and culture.

Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic, acneform papular and pustular eruption which involves the skin of the midface, nose, cheeks and forehead. Hallmarks are cutaneous erythema and hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands, especially over the nose. The condition is most common in women ages 30 to 50, and accounts for many of the chronic red eyes that don't respond well to topical medications. Ocular manifestations include blepharitis, chalazion, catarrhal ulcers of the cornea and nodular conjunctivitis. Rosacea keratitis usually progresses as an asymptomatic corneal vascularization with central opacification in advanced cases. Standard therapy is lid hygiene and tetracycline, but recent suggestions include anti-ulcer therapy with an appropriate antibiotic. Topical metronidazole is used for the manifestations of rosacea on the skin, but an ophthalmic preparation is not currently available.

Treatment of Allergic Conjunctivitis

Early detection of and differentiation between different types of allergic conditions of the ocular surface are crucial to successful management of ocular allergy in contact lens wear. Once lens wear has been discontinued and the other antigens have been removed (if possible), choosing the proper therapeutic agent depends on the severity of signs and symptoms. A simple remedy includes cold compresses, which stabilize the mast cell and cause vasoconstriction. Artificial tears (unpreserved if using more than four times per day) may also be used as an effective adjunct to dilute the allergen.

In allergic and vernal keratoconjunctivitis, levels of histamine and other mediators are significantly elevated. Topical antihistamines can be the drug of choice when itching is the primary symptom, and concomitant use of oral antihistamines can relieve systemic allergic symptoms. Most of the topical antihistamines include a vasoconstrictor. The combination has been shown to be more effective in reducing the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis than either agent alone. There are generic options as well as five commercially available topical antihistamines: pheniramine maleate (Naphcon A), pyrilamine maleate (Prefrin A), antazoline phosphate (Vasocon A and Abalon A), emodastine (Emadine) and lovacabastine (Livostin). Livostin and Emadine are the only topical antihistamines that are not combined with a vasoconstrictor, but they still have some decongestant properties and are very potent drugs. The absence of the alpha-adrenergic vasoconstrictor makes them a more attractive choice for patients with cardiovascular disease or for patients taking MOA inhibitors. These topical antihistamines may block histamines and cytokine release, which is responsible for recruiting other inflamed cells, dilating blood vessels and swelling surrounding tissue. Oral medications are often a necessity since allergic conjunctivitis may be coupled with allergic rhinitis. Several new oral medications are available that do not carry the risk of previous options, namely drowsiness and life threatening tachyarrhythmia. Cetirazine (Zyrtec), terfenadine (Allegra) and loratadine (Claritin) are currently the most popular drugs employed for allergy related symptoms due to their minimally sedating effect.

When conjunctival inflammation is the main finding, topical NSAIDs are a safe and effective treatment. Although ketorolac (Acular) is the only NSAID approved for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis, diclofenac (Voltaren) seems to have similar efficacy and safety. Their mechanism of action includes blocking the cyclooxygenase pathway and formation of inflammatory mediators. While effective for allergy-associated pain relief, these drugs are often insufficient to manage severe cases of atopic disease and increased epithelial toxicity is likely with prolonged use, especially in the dry eye patient.

Topical steroids are reserved for severe atopic, allergic and vernal reactions of the external eye. Topical corticosteroids are the most effective anti-inflammatory drugs available for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis. They prevent the hydrolysis of arachidonic acid, thus blocking the formation of leukocytic migration. This stabilizes lysosomal membranes, inhibits neovascularization, inhibits histamine synthesis and decreases capillary permeability. Despite their ability to suppress allergic cascades, their use is fraught with potential ocular complications such as cataracts, glaucoma, delayed wound healing, enhanced susceptibility to infection and rebound anterior uveitis. Therefore, topical corticosteroids with poorer corneal penetration (i.e. rimexolone, loteprednol, fluorometholone and hydroxymesthrone) may be useful in treating allergic reaction while minimizing risk. Once the severity of symptoms diminish, other anti-allergy medications should be substituted.

Broader spectrum efficacy and relative safety makes topical mast cell stabilizers attractive, despite the fact that they require a loading time of a few days and continuous use. Lodoxamide (Alomide) is more potent than disodium cromoglycate and is better for minimizing eosinophil activation. Nedocromil sodium is still not commercially available in this country. With the recent addition of combination topical agents like olopatadine (Patanol), a mast cell stabilizer/antihistamine with greater efficacy is available. A twice-daily dosing aids the contact lens wearing routine. Patients should allow for at least a five-minute break before inserting their lenses after topical agent instillation.

Improvement of the delivery system of cyclosporine A (0.5%-2% solution) in the near future may offer a more efficacious and slightly less toxic alternative to our current drug regimen for the treatment and management of severe ocular allergy, especially when there's any corneal involvement. To those with systemic involvement, immunization is gaining acceptance whereby a whole new set of blocking antibodies are established.

Summary

A broad range of therapeutic approaches exist in managing the contact lens wearer with allergies. With a careful history, scrutinizing clinical examination and appropriate use of available drugs, most patients, including allergy sufferers, can enjoy safe contact lens wear. Give careful attention to lens wearers at an increased risk for ocular surface insult and additional corneal morbidity (especially patients with systemic allergic disease). For patients who pose too great a risk with contact lenses, spectacles and refractive surgery remain a viable option.

To receive references via fax, call (800) 239-4684 and request document #35.

|