Investigating Contact Lens Interchangeability

BY ARTHUR B. EPSTEIN, OD, FAAO & JOSEPH M. FREEDMAN, OD

JANUARY 1998

To examine the impact of mail-order contact lens substitution, these practitioners replaced the habitual lenses of successful patients with a comparable design from a different manufacturer.

Disposable contact lenses, introduced in 1988, were designed to address some of the issues raised by the extended wear scares of the middle and late 1980s. In some ways, however, disposable lenses have actually created more problems than they have solved.

Despite fewer complications, greater ease of wear and many other benefits of disposable lenses, they have fostered a profound and irreversible change in the way contact lenses and contact lens practitioners are perceived. For example, our patients are no longer just patients -- they have become consumers. Contact lenses are no longer a medical device -- they are now a consumer item with bar coding and an SKU. Even as doctors we haven't been spared by this perceptual reinvention, as many of our patients treat us more as a means to obtain a prescription for contact lenses than as the guardians of their ocular health they once believed we were.

For better or worse, disposable lenses are now king, and their increased popularity has helped spur the growth of mail-order and alternative contact lens dispensing. It should come as no surprise that disposable contact lens wearers are nearly twice as likely as conventional lens wearers to purchase lenses through these alternative routes. Both state and federal laws protect the contact lens consumer by requiring a prescription before a contact lens can be dispensed, but enforcement of these laws has been limited. This laxity has encouraged some mail order vendors to become more aggressive, and some patients have even been known to call in their own prescription read directly from the contact lens packaging. Underlying the consumerization of contact lenses is the concept that all contact lenses are essentially the same and that one can be substituted for another -- without professional involvement.

Our Incentive to Take Action

Although we were generally aware of these types of activities, we were still shocked to discover that a mail-order firm had substituted one contact lens brand for another for one of our patients without consulting us. The company had replaced the Biomedics55 lenses (Ocular Sciences/American Hydron) that we had prescribed for our patient with SofLens66 lenses (Bausch & Lomb). Fortunately, our patient returned for evaluation when he encountered problems with the substituted lenses.

Following this incident, we conducted an informal survey using the Internet-based Optcomlist and found that lens substitution is becoming increasingly common. One colleague described how a patient's rigid lenses were replaced with soft lenses, and another told of how plus was added to a patient's monovision prescription when the patient complained about not seeing well up-close. In both cases, the doctor was not involved in the decision.

Eye care professionals understand that contact lens fitting is as much an art as a science because every contact lens has unique qualities and fitting characteristics. Some of these differences may be subtle, but as every contact lens clinician eventually discovers, even lenses with similar specifications do not always perform alike. Our experience has been that these performance differences can sometimes be immense, so it seemed unlikely to us that unsupervised lens substitution would result in a properly fitted contact lens. To examine in a controlled clinical setting the result of a substitution like our patient experienced, we substituted SofLens66 for Biomedics55 lenses in 12 randomly selected, successful Biomedics55 wearers.

Procedure

Prescriptions of the 12 patients who had worn Biomedics55 lenses on a two-week daily wear basis for at least one year ranged from -1.00D to -6.00D, and average K readings ranged from 42.00D to 46.00D. As a participation incentive, we told patients they could have two boxes of the lenses of their choice (provided they fitted properly) at the conclusion of the study. We examined all patients with their habitual Biomedics55 lenses and performed the following procedures: corrected visual acuity (with lenses); overrefraction and visual acuity; evaluation of lens fit; refraction and visual acuity without the lenses; corneal topography; and slit lamp examination.

Patients rated the Biomedics55 lenses on a scale of 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) for comfort, vision, handling and overall performance. They also listed typical average daily wearing time and the average length of time that their lenses remained comfortable.

We then refitted all patients with SofLens66 according to the manufacturer's published fitting guide. Two fitting parameters are available for SofLens66, flat-medium (FM) and steep-medium (SM). To ensure the most appropriate lens selection, we tried both parameters when the initial lens selection fitted poorly or was uncomfortable. We evaluated all patients at dispensing to confirm acceptable lens fit and vision.

Patients wore the SofLens66 lenses for a two-week period, making no changes to their habitual lens care or wearing habits during the test period. We conducted follow-up examinations exactly two weeks after dispensing the test lenses. We evaluated for fit and vision with and without overrefraction, and again questioned the patients about average wearing time and the length of time the lenses remained comfortable. We also repeated corneal topography and slit lamp examination. At the conclusion of the study, patients revealed their subjective response to both lenses as well as their final lens preference.

Results

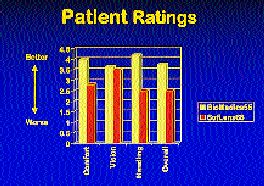

Of the initial 12 patients, nine completed the study. Two patients dropped out during the first two days and one dropped out in the second week, citing discomfort with the SofLens66. Table 1 and Figure 1 illustrate average subjective patient ratings. The scale ranges from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). All findings were clearly significant except for vision ratings which were essentially the same for both lenses.

|

FIG. 1

|

FIG. 2

Patient comments were also telling. Six patients reported discomfort with the SofLens66, five reported excessive movement and three complained of poor vision. Five patients felt that SofLens66 handled poorly compared to the Biomedics55, and four reported that the SofLens66 was less comfortable or performed differently in one eye compared to the other. Table 2 and Figure 2 illustrate average wearing time and length of comfortable wear.

Objective findings were mostly unremarkable, but we observed fluorescein staining of the cornea in five patients wearing the SofLens66. Staining occurred predominantly in patients reporting awareness of lens movement. Although any corneal disturbance is worrisome because it may lead to more serious complications, a larger and more comprehensive study will be necessary before any conclusions can be drawn about such a relationship.

At the conclusion of the study, one patient strongly preferred SofLens66, one reported no difference between the two lenses and seven strongly preferred the Biomedics55.

Conclusion

Despite apparent similarities in lens design and manufacturing mode, this study shows that there are substantial fitting and performance differences between the SofLens66 and the Biomedics55 lenses. This study was not intended to be an exploration of comparative lens performance but rather an investigation of contact lens interchangeability. It proved that an overwhelming majority of successful Biomedics55 wearers preferred a lens that had been carefully and purposely prescribed by their doctor. The results also strongly suggest that SofLens66 was not directly substitutable for Biomedics55. However, our clinical experience has revealed that some lenses are inherently more interchangeable than others based on their design.

We believe unauthorized and unsupervised lens substitution is a potentially dangerous practice that can have significant consequences. This is the primary reason why contact lens distribution is by prescription only. Controlling the contact lens supply is not a consumer rights issue or a practice management issue -- it's a public health issue.

The results of our study show that unsupervised lens substitution is clinically inadvisable and may induce complications in contact lens wear. These data also vindicate contact lens manufacturers who limit distribution of their products to sites where patients can be clinically monitored and where professional care is available.

Other Considerations

Motivation -- Why would a distributor of a federally regulated device risk breaking prescription laws? There are several possible explanations. First, there is strong financial motivation. Mail-order contact lens distribution is a big and profitable business.

For eye care professionals, contact lens dispensing is usually the culmination of extensive clinical activities; for mail-order distributors, it may be nothing more than a simple business transaction. Some contact lens manufacturers limit distribution of their products to health care professionals only. Rather than lose a potential sale, it appears that some mail-order firms will substitute one brand of contact lens for another. For example, Ocular Sciences' "no doctor -- no slit lamp -- no contact lenses" philosophy, instituted in 1993, has encouraged some alternative suppliers to attempt to substitute Ocular Sciences' brands with products from other companies. In addition, enforcement of medical device dispensing regulations has been so limited that it has not served as an effective deterrent. Attempts by the eyecare profession to limit contact lens distribution have met with failure, as alternative lens distributors have painted our justifiable concerns as self-serving and financially motivated.

We Can't Claim Innocence -- The contact lens community must accept part of the blame for this misconception. We have not effectively made the case that contact lenses are medical devices that require professional supervision and that their misuse can have deleterious effects on ocular health. We have failed to prove that contact lenses are unique and that substituting one lens for another requires professional supervision, just as when one medication is substituted for another. We have not consistently reported violations of federal and state laws to the appropriate authorities nor have we effectively educated the public that contact lens dispensing is just one small part of the overall fitting and wearing process. And finally, many of us do not consciously or consistently support the companies who support our profession and our patients by limiting contact lens distribution to professionals.

Uncontrolled Access? -- Although it is possible that unrestricted contact lens distribution could reduce the lens costs to consumers initially, what would be the risks associated with this type of deregulation? Consider the effects of excluding physicians from the decision-making process by allowing patients to prescribe their own medications. While the dangers of uncontrolled access are clearly recognized by the pharmaceutical and medical communities, the potential danger to the public appears less obvious when it comes to contact lenses.

In a more global sense, the elimination of the doctor in the fitting process is a step back to early days when patients selected their own glasses from a rack. It seems odd that in a time of technological enlightenment and financial prosperity the importance of professional care seems to be lost on so many.

This study was supported by a grant from Ocular Sciences/American Hydron.