CONTACT LENS DROPOUTS

Preventing Contact Lens Dropouts

BY

JOANNA COSGROVE

March 2001

Contact lens practitioners offer solutions to circumvent this growing problem.

Never before has there been such an expansive breadth of contact lenses available to suit so many patient needs. But countering the product advancements is an alarming statistic that shows one-time contact lens wearers turning away from, or "dropping out" of, contact lens wear at a disappointing rate.

"Contact lens abandonment is a perplexing problem and one which the industry as a whole has been reluctant to tackle," says Desmond Fonn, professor and director, Centre for Contact Lens Research, School of Optometry at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. "The most recent market research survey (1999) that I have seen suggests that there are approximately 10.5 million dropouts in the United States. This represents a huge loss in income to the eyecare industry."

In distinguishing between permanent and temporary abandonment, Dr. Fonn places a realistic estimate of permanent abandonment at about 15 percent per annum and temporary at closer to 30 percent. "We found that in the latter category, half of the estimated 30 percent would discontinue lens wear for two years or longer. Many of the 30 percent would discontinue lens wear more than once, resulting ultimately in permanent abandonment," he says. "This is why discontinuation is such an enormous financial loss to the eye care industry."

Mark André, FAAO, Director of Contact Lens Services, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, Ore., agrees, citing a more startling set of figures. "Between two and 2.2 million people drop out of contact lens wear annually, which equals almost 10 percent of the contact lens wearing population. That's a big annual failure rate," he says. "The reason the industry is not growing is because for every person coming in, there's one person leaving."

Understanding Why

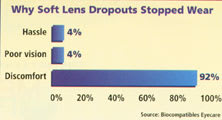

In a nutshell, contact lens abandonment can be chalked up to two general causes: discomfort and inconvenience.

Chiefly, irritation and dryness must be eliminated, but the question is how. "There are currently a variety of strategies that practitioners employ, and unfortunately these are numerous and point to our lack of fundamental understanding of what produces ocular irritation with lens wear," says Dr. Fonn. "The other problem of inconvenience is easier. Inconvenience can be overcome by daily disposables which eliminate care and maintenance, or extended wear of high Dk silicone hydrogels which offer a form of permanent correction and partial elimination of handling and care. Our five years of research with high Dk silicone hydrogels suggests that these are safe to use for wear, and the vast majority of our research subjects are very happy with these lenses."

For many contact lens wearers, the hassle associated with wear and care also leads to discontinued use. A number of patients still have difficulty with lens handling, especially insertion, with disposable lenses. "One of the more challenging patients is the one who says he tried disposable lenses and did not like them," says Peter Bergenske, OD, faculty member at Pacific University in Forest Grove, Ore. "This is almost always a patient who has trouble handling a thin lens. Our choices in conventional lenses have dwindled, but it is still possible to fit with a low to moderate water content lens that handles easily."

While discomfort and inconvenience rank as the most common reasons why patients discontinue wearing contact lenses, prescribing the right lens is often the most overlooked best place to begin, especially when it comes to fitting the presbyopic and astigmatic patient. "Patients often perceive that their discomfort, poor vision or hassle are unsolvable problems, meaning they'll be fit with a pair of lenses and if that particular pair doesn't work, they think that there are no other alternatives," says Gary Gerber, OD, Hawthorne, New Jersey. "I continually counsel my clients that the first time they fit a patient, they should always let the patient know, 'If by chance these lenses don't work, if you don't see well, if they don't feel quite right, it doesn't mean you can't wear contact lenses, it means you can't wear these contact lenses.'"

Presbyopia claims a certain number of contact lens wearers, and while developments in bifocal lenses have helped tremendously, they still don't meet the needs of many presbyopes, says Dr. Gerber. "Contact lens fitters must be adept at applying the many variations on bifocal, monovision and spectacle-supplemented solutions to presbyopia," he says.

It's important to fit patients with lenses that give them the vision they're used to seeing with glasses. "About 45 percent of patients have at least 0.75D of astigmatism," comments André. "When you look at the number of patients that are wearing toric soft lenses, about 15 percent of the soft lens wearing population, a significant part of patients are wearing spherical lenses when they should be wearing a lens that corrects astigmatism. Fatigue comes from poor vision. With all the lens options we have now, toric soft lenses, disposable torics, RGPs, there's no excuse for putting a spherical lens on an astigmatic eye."

|

What Would Influence Soft Lens Dropouts to Try Again? |

|

| ATTRIBUTE | RANK |

Increased comfort |

1.47 1.89 2.00 2.12 2.32 2.41 2.63 IS* IS* |

| *insufficient sample, too few responses | |

| Source: Biocompatibles Eyecare | |

Counteracting the Problem

Now that the dropout problem has been brought into focus, what can practitioners do to circumvent this phenomenon? Dr. Gerber suggests that dropout rates would be favorably impacted with the increased use of single-use lenses. "I don't track dropout statistics, but I'd bet that you would definitely see a trend showing that the sooner the lenses are disposed of, the fewer dropouts there are," he says. "It makes perfect sense: if you fit daily disposables, you eliminate all of the reasons patients drop out in the first place: hassle (there's no solution), comfort (cleaner lenses equal more comfort), and improved vision (cleaner lenses equal better vision)."

While that may be true, André proposes the problem goes beyond prescribing the right lens, a lesson he inadvertently learned personally. "In addition to our specialty contact lens practice, my partner and I also work with a laser vision center, and we see a fair amount of patients go through there that aren't candidates, or who are candidates and proclaim themselves as contact lens failures," he says. "Our first enlightening experience was about five years ago when a study was being conducted on one of the newer lasers. They had to do 100 patients, one eye only, and the patient had to wait six months to do the second eye. The patient couldn't wear glasses because the other eye was already corrected, so we had to fit all of them in contact lenses. All of them said they'd worn contact lenses or tried contact lenses and couldn't do it, so none of them expected to be fit successfully. However, we had 97 of the 100 wear the lenses all day without any discomfort."

But André stresses the success wasn't entirely attributed to great fits. "Actually, it was a testament to our inability to pick up problems," he says. "We put all of those patients in single use lenses. The problem was they were reacting to the care products they were using, or they weren't cleaning their lenses properly."

André contends that not identifying solution problems or patients who are inadequately cleaning their lenses ranks as one of the biggest reason patients drop out of lenses. "Solution problems can be so subtle," he says. "They can create a mild inflammation of the tissue that isn't serious enough to make the eyes red and painful, but does make them slightly uncomfortable, somewhat dry and scratchy. Pretty soon patients cut back on their wear time and eventually they are in glasses more than they are in contact lenses and perhaps they even check into refractive surgery.

"Typically we write off lens discomfort as the patient getting older and the eyes drying as a result. But a lot of it is a dirty lens or a lens that's been soaked in an irritating solution," he continues. "It's a significant problem. Sometimes changing a care system without changing the lens makes a huge difference."

Dr. Bergenske concurs, adding that "going preservative free still is best for many patients who are vaguely symptomatic, while single-use disposables are great for getting the former contact lens wearer back into contact lenses even if only on a part time basis, and these really avoid the solution problems."

When counseling a prospective contact lens patient, it's in a practitioner's, and patient's, best interest to take each aspect of the lens experience into consideration in order to provide the best service and create a satisfied repeat patient.

Joanna Cosgrove is a freelance writer based in Media, PA.