ALLERGY AND CONTACT LENSES

Allergies and Lens Wear: How to Get the Itch Out

Follow these tips to prevent allergies from sabotaging contact lens wear.

By David W. Hansen, OD, FAAO

Estimates indicate that 20 percent of the general population, or more than 50 million people, suffer from allergic conjunctivitis. This is the primary allergic reaction among other conditions such as seasonal and perennial allergies, vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC), also known as contact lens papillary conjunctivitis (CLPC). The hallmark symptom for all four conditions is itching. Other systemic characteristics of the immunological response include hay fever, sinusitis, asthma, headache, skin rash or even gastrointestinal disorders.

An allergen, which could include many hundreds of substances, often presents as an innocuous agent that does not cause a response in the nonallergic patient. However, a patient may become susceptible with allergen exposure and produce an immunoglobulin (Ig) E antibody. IgE antibodies attach to allergens, and the allergen complex binds to cells and starts escalating events that eventually may present in the eye as itching.

Acquired immunity begins with B and T lymphocyte production in the bone marrow. B cells mature in the bone marrow and are responsible for humoral immunity. When B cells encounter specific antigens in the blood or lymphatic vessels, they produce plasma cells that make millions of antigen-specific soluble antibodies.

T cells mature in the thymus and contribute to cellular immunity by directly killing the infected blood cells and producing lymphokines, which damage tissue and attract other immune cells. T cells also help regulate the immune response. Allergen exposure may initiate the allergic reaction, which produces allergen-specific IgE antibodies that attach to circulating mast cells or basophils. The outer cell membrane of each mast cell contains tens of thousands of IgE antibodies, and there are approximately 50 million mast cells in the human eye. When two adjacent IgE antibodies bind to a specific allergen, cell membrane permeability changes and the cell releases preformed mediators, initiating the allergic reaction within seconds. Mediators found in ocular allergy disease are histamine, platelet-activating factors and eosinophil chemotactic factors. Histamine is what produces the itching, vasodilatation and edema. Eosinophils release a major basic protein whose elevated levels cause the degranulation of the mast cells.

|

|

|

|

|

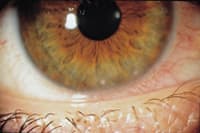

Figure 1. This retention cyst is an example of a Type I allergic reaction. |

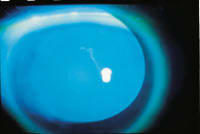

Figure 2. Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis is a Type IV reaction. |

|

Allergic Mechanisms

Coombs and Gell classified and described foreign mechanisms for the allergic reaction and designated them as Types I through IV.

Type I is an immediate and anaphylactic, or an IgE-mediated, reaction. This hypersensitivity occurs when a patient is re-exposed to an antigen, such as a drug, pollen or other airborne stimuli. Mast cell degranulation releases vasoactive substance (histamine), which may trigger an immediate allergic response. Hay fever, allergic conjunctivitis, vernal conjunctivitis, asthma and severe reactions to bee stings and certain drugs, especially antibiotics, can result in this response (Figure 1).

Type II, referred to as cytotoxic, cytolytic or cell-stimulating reactions, result when an exogenous antigen combines with an IgG or IgM antibody. The antibody and antigen attach to a cell, causing cell destruction by different mechanisms. Examples include organ transplant graft rejection, drug-induced hemolytic anemia and mismatched blood transfusions.

Type III reactions, known as immune-complex reactions, result when circulating antigen-antibody complexes produce an inflammatory response. Examples may include the Arthus reaction, serum sickness and symptoms associated with systemic lupus erythemathosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis.

Type IV reactions are also called cell-mediated or delayed reactions. These occur when the antigen interacts with T-lymphocytes rather than the antibody, which is the case in the three other reactions. Allograft rejection and contact dermatitis are two examples of a Type IV hypersensitivity. Ocular conditions include atopic keratoconjunctivitis, vernal conjunctivitis and blepharokeratoconjunctivitis induced by preservatives in drugs and contact lens solutions (Figure 2).

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Four essential factors contribute to an ocular allergy: environmental, genetic, medication and cosmetic and device.

- Environmental Air pollution and the environment can affect geographic climate conditions and produce allergies, especially vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Industrial pollutants, auto emissions and other environmental agents may act as allergens.

- Genetic Family history is important in allergy. A 50 percent likelihood exists that an allergic patient has a family history of the condition, usually in a parent. Atopy is an allergy that has a heredity predisposition. A child who has one atopic parent is four times more likely to develop an allergy. The chance increases to 10 times if both parents are atopic.

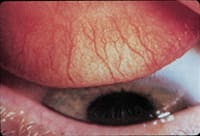

- Medication and cosmetic Medications, cosmetics, perfumes, house dust, animal dander, nail polish, certain metals, fabric softeners and products such as dryer sheets are commonly responsible for the allergy response (Figure 3). Bacterial toxins, viruses, molds, pollens and yeast can also initiate sensitivity to susceptible individuals.

- Device GPC can result from sensitivity to contact lenses, prosthetics, sutures, cyanoacrylate glues and extruding scleral buckles.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Patient symptoms are the most critical factor in diagnosing an allergic response and determining the underlying etiology. You should also determine whether the allergy is seasonal or perennial. Allergens present throughout the year include feathers, cosmetics, animal dander, house dust, foods and molds. Some allergies increase in severity during the winter months. For example, house dust allergies may worsen when forced heat is used. Pollen allergies such as ragweed are more common during the fall months and continue until the first frost. Knowing when pollination occurs for offending indigenous plants is key when evaluating seasonal allergies. Common ocular allergy signs include the cardinal trademark of itching, as well as tearing, burning, photophobia, pressure and increased mucus secretion.

Careful assessment of the external eyelids as well as the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva usually shows swelling, erythema, induration and eczema. Carefully analyze mucus discharge for its color (clear or yellow), and its consistency (ropy or stringy). These two areas can serve as diagnostic tools for isolating the problem and helping manage the condition. Typical conjunctival signs in the allergic patient include hyperemia, edema, dilated vessels, papillary changes and erythema of the tarsal conjunctiva. Corneal abnormalities, such as superficial punctate keratitis, may help you differentiate between a staph infection and an allergic response.

Observe the eye and surrounding tissues, and I advise that you perform additional allergy testing when you have identified more than one system. You can order additional tests though a workup of a systemic allergist, or an otolaryngologist (ENT) who deals with allergies can perform an external examination of the eye and adnexa. Careful assessment with a biomicroscope can usually show whether most conditions are bacterial, viral or allergic in etiology.

An excellent test for diagnosing allergies, especially allergic conjunctivitis is the Mag test or Mag sign. Nicholas Maganias first reported this test in 1981. A clinician performs the test by pulling down the lower eyelid while the patient looks upward. The test is positive if the examiner notices a half moon or crescent bulging out, demonstrating proptosis of the lower eyelid. The Mag sign is pathognomonic of significant allergic conjunctivitis (Figure 4).

|

|

||

|

Figure 3. Medication-induced dryness, dellen and vascular limbal hyperemia. |

Figure 4. The Mag sign indicates significant allergic conjunctivitis. | |

Types of Allergic Conjunctivitis

Seasonal Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC) Patients suffer annually from seasonal environmental allergies, usually comprised of hypersensitivity to pollens, grasses, trees, animal dander or molds. Ocular symptoms usually involve chemotic conjunctiva and swollen lids. Your duty is to try to identify the offending allergen and prescribe its avoidance if at all possible. Managing these patient requires elimination of the allergen and/or proper use of anti-allergy drugs. Practitioners should focus specifically on the personal and family history of other atopic conditions and circumstances present in the family. Seasonal allergies typically produce a thin, watery discharge and do not involve the cornea. If the patient exhibits thick, ropy discharge with severe itching and corneal involvement, he most likely has vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) rather than a seasonal allergy.

Acute allergic conjunctivitis (AAC) is also known as hay fever or seasonal conjunctivitis. Itching is the most predominant sign and patient complaint. Most presentations are bilateral due to the airborne antigens affecting the eye, but a unilateral response can occur when hand contact introduces antigens such as animal dander to the eye. These patients also usually have a history of allergic problems such as rhinoconjunctivitis or food allergies. Other clinical findings may include superficial conjunctival vasodilatation, chemosis, mild eyelid edema, a white stringy mucus discharge or occasionally no signs at all (Figure 5).

Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis (PAC), also called chronic allergic conjunctivitis (CAC), is similar to acute allergic conjunctivitis but occurs with seasonal exacerbations and is attributed to conjunctival exposure to dust mites and animal dander. It usually occurs in adults between the ages of 20 and 50. The classic systems include itching, hyperemia (Figure 6), chemosis, upper eyelid edema, lacrimation, chronic irritation, mucus discharge and photophobia. Rare findings include corneal involvement, papillary reaction and the presence of eosinophils and conjunctival scraping.

Environmental protection from exacerbating allergens may be extremely difficult, so you must individualize treatment. Start with cold compresses to relieve the symptoms and avoidance of the offending antigen. Topical antihistamines such as Livostin (levocabastine, Novartis), and Emadine (emedastine, Alcon) relieve moderate to severe allergic conjunctivitis symptoms. Mast cell stabilizers such as Alomide (lodoxamide, Alcon), Crolom (Elan Pharmaceuticals) and Opticrom (cromolyn, Allergan) provide minimal relief from acute allergic conjunctivitis symptoms because they lack antihistaminic activity. They can be very effective, however, for prophylaxis for seasonal and perennial conjunctivitis because they prevent mast cell degranulation. Patanol (olopatadine, Alcon) and Zatidor (ketotifen fumarate, Novartis) are combination antihistamine/mast cell stabilizers that are approved to relieve itching due to seasonal and perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Twice-a-day dosage at six- to eight-hour intervals is recommended. The FDA has approved Patanol for children as young as 3 years of age. It is excellent for contact lens wearers because they can instill one drop before and after lens wear to relieve symptoms associated with ocular seasonal allergies.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as Acular (ketorolac, Allergan), also effectively relieve itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis, but they reportedly cause significant stinging upon instillation.

In severe cases of a seasonal allergic conjunctivitis, corticosteroids remain the most effective treatment. These medications stabilize mast cells and prevent activation of the arachidonic acid cascade. Try to use traditional corticosteroid medications for only a limited basis due to the risk of side effects, including ocular hypertension and cataract formation. The new "site-specific" corticosteroids such as Alrex (loteprednol 0.2%, Bausch & Lomb) provide effective treatment of allergic conjunctivitis with less side effects than other corticosteroids. This drug becomes inactive shortly after the target tissue absorbs it. Prescribe Alrex at four times a day dosing for seasonal allergy relief. Practitioners should consider Lotemax (loteprednol 0.5%, B&L) or Vexol (rimexolone, Alcon) for hyperacute allergic conjunctivitis conditions. These medications have reduced side effects and the advantage of higher potency for treating seasonal allergies.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5. Seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. |

Figure 6. Superior lid hyperemia from chronic allergic conjunctivitis. |

|

Oral antihistamines are effective for patients demonstrating allergic conjunctivitis and allergic rhinitis or sinusitis. Over-the-counter (OTC) antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine and Claritin (loratadine) are effective but may cause drowsiness. Prescription antihistamines such as Allegra (fexofenadine), Clarinex (desloratadine) and Zrytec (cetirizine) have minimal sedating effects and assist with long terms allergic symptom management. Similisan #2 (a homeopathic preparation) has clinically improved hyperemia and itching associated with allergic conjunctivitis. It is a preservative-free solution containing extracts of honey bee, eyebright and cevadillas. Additional studies are necessary to determine its efficacy and safety.

Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) is a Type I hyperinflammatory reaction that has a strong correlation with atopic dermatitis. AKC accompanies atopic dermatitis in roughly 25 percent to 50 percent of atopic dermatotic patients. This perennial condition often worsens during the winter due to the dryness associated with home heating. Major symptoms include ocular itching, burning and photophobia. It is more prevalent in the second decade of life and lacks the strong seasonality seen in other ocular disorders. Other clinical findings may include watery discharge, photophobia, lid edema, conjunctival vasodilatation, chemosis, tarsal papillae and atopic cataracts. Corneal involvement, which may be sight-threatening, includes superficial peripheral keratitis with or without infiltrates, ulcers, keratoconus, increased incidence of herpes simplex keratitis and peripheral neovascularization. Atopic cataracts are anterior subcapsular cataracts with a "stretched bear rug" appearance. They occur in 10 percent to 15 percent of AKC patients and rarely interfere with vision.

Eyelids with AKC are usually swollen and eczematous, which may be a differentiating sign. Conjunctivitis may be cicatrizing (scarring, hypertrophia) (Figure 7).

Advise AKC patients to avoid eye rubbing and antigens. Cold compresses and preservative-free artificial tears, along with topical antihistamine-vasoconstrictors, may relieve minor AKC symptoms. NSAIDs and antihistimanes relieve moderate symptoms, but mast cell stabilizers and mast cell-antihistamine combinations are currently the best choice for long-term management. Topical corticosteroids are effective only for short-term management with AKC flare-ups.

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis (GPC) Some believe GPC is a chronic inflammatory disorder, while others believe it results from mechanical trauma whose concomitant allergy contributes to its severity. GPC is associated with contact lens wear, ocular prosthesis and postoperative keratoplasty sutures. It occurs more with soft lens materials than gas permeable materials. You will find clinical GPC signs in most patients who have decreased contact lens tolerance, foreign body sensation and discomfort upon removal of their contact lenses. Initial theories assume that GPC is a Type I hypersensitivity reaction between the deposits on the contact lens or prosthesis and the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Other theories suggest that GPC results from a contact lens edge inducing chronic trauma to the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Patients report early eyelid discomfort, blurring due to coating build-up on the contact lenses and mild mucus discharge in the eye. Advanced GPC symptoms may include excessive mucus production, lacrimation, burning, foreign body sensation during lens wear and conjunctival vasodilatation (Figure 8).

The classic finding involves small uniform follicles in the upper palpebral conjunctiva, where the lid passes over the contact lens edge approximately 20,000 times per day. As these papillae grow in size they are usually smaller, flatter and more uniform than the giant papillae associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC). Scraping of GPC patient conjunctiva reveals elevated levels of mast cells and eosinophils in the conjunctival epithelium, but significantly less than in VKC. In advanced cases, corneal involvement will include punctate epithelial keratitis or corneal erosions, which can progress from mild to severe and cause significant photophobia. Cellular infiltrate does not elevate histamine levels and is not characteristic of allergy.

As with other allergies, remove the affected antigen. This means replacing the lens modality or refitting with a new material. If the patient wears a soft lens, try replacing it with a daily disposable soft lens or a GP lens. Proper lens hygiene and artificial tear use may improve symptoms. Cleaning and/or polishing a coated prosthesis or removing an offending PKP suture may also help relieve symptoms.

Treating GPC is as controversial as its etiology. Cold compresses, preservative-free artificial tears and topical antihistamine/vasoconstrictor combinations may provide relief for mild GPC. Topical antihistamines such as Livostin, mast cell stabilizers such as Crolom and Opticrom and NSAIDs such as Acular have effectively treated GPC, but require many weeks and months to resolve the symptoms.

Mild to moderate GPC may require Patanol. In severe cases, topical steroids such as Flarex (fluorometholone acetate 0.1%, Alcon) and eFlone (Novartis) may help reduce papillary hypertrophy and injection.

Many patients may benefit from short-term use of cromolyn sodium and lodoxamide tromethamine concurrently with contact lenses. Cromolyn sodium does not accumulate in soft lenses. Neither is currently FDA-approved for use with contact lens wear, so advise patients that their use is off-label.

The FDA approved Lotemax for treating postoperative inflammation as well as steroid-responsive inflammatory condition of the bulbar and palpebral conjunctiva, the cornea and other anterior segment structures. This drug is site-specific and may become the treatment of choice for long-term GPC problems. I don't usually recommend oral antihistamines for treating GPC.

Viva-Drops (Corneal Sciences Corporation), Bion Tears (Alcon), Tear Naturale Free (Alcon), Refresh Plus (Allergan), Refresh Endura (Allergan), Ocucoat PF (B&L), TheraTears Liquigel (Advanced Vision Research), Systane (Alcon), the soon to be released Restasis (Allergan) and dry eye therapy may be useful lubricants for GPC. Mast cell stabilizers deliver significant therapeutic benefit with GPC, but eradicating the antigen remains the most effective method.

Patients with allergic symptoms often have dry eyes as their primary problem, so rule out any tear deficiency in chronic GPC conditions. Meibomianitis and blepharoconjunctivitis conditions may reduce meibomian function and could produce mechanical irritation. Use disposable soft lenses or GP lenses in combination with medical therapy for patients who absolutely cannot discontinue contact lens wear.

Contact Allergic Conjunctivitis Ophthalmic practices frequently encounter this Type IV hypersensitivity reaction, which commonly results from eye medications, cosmetics and soaps (Figure 9). Patch testing may help identify the antigen, which causes dermatitis and inflamed eyelid margins. Classic signs include inflammation presented as hyperemia, swelling and warmth.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 7. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis. |

Figure 8. Giant papillary conjunctivitis. |

Manage these patients by removing the causative agent and supportive treatment with lubricants. When acute, use topical antibiotic steroids in and around the eye to reduce inflammation and return the tissue to a healthy condition. Topical corticosteroids most effectively treat all types of ocular inflammation and allergy.

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a recurring seasonal condition, which worsens in the warmer months and is most common in warm dry climates. It affects males more than females and is also more prevalent between the ages of 3 and 25. Make sure you differentiate this Type I hyperinflammatory reaction from other allergy tendencies. Conjunctival scrapings reveal that VKC patients have elevated levels of mast cells and eosinophils in their conjunctival epithelium. The most important clinical signs include large non-uniform cobblestone conjunctival papillae on the back of the superior tarsus, Horner-Tranta's points or dots (gelantinous, white clumps of degenerated eosinophils at the superior limbus), areas of superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) and, in severe cases, well demarcated, sterile, superiorly located corneal shield ulcers. The excessive mast cells and chemical mediators on the conjunctival surface cause the exaggerated allergy symptoms.

VKC is typically bilateral, and symptoms include itching, burning, lacrimation, photophobia, foreign body-sensation and mucus discharge with cord-like yellowish elastic properties.

Advise VKC patients to avoid hot dry climates and excessive eye rubbing. Cold compresses, preservative-free artificial tears and topical antihis-tamine/vasoconstrictor combinations may relieve mild symptoms. Antihistamines and NSAIDs provide relief from moderate symptoms. I recommend mast cell stabilizers like Alomide and mast cell antihistamine combinations like Patanol. Topical corticosteroids are effective for short-term treatment, but don't use them for long term or chronic resolution of the problem. Studies indicate that aspirin 600mg. qid may be effective, but always exercise caution with possible side effects of gastritis, decreased coagulation and Reye's syndrome, especially in children.

VKC patients who present with shield ulcers also need aggressive cycloplegia (atropine 1%, homatropine 5%, or scopolamine 0.25%, bid) and topical antibiotic (Tobrex [Alcon], Ciloxan [Alcon], Ocuflox [Allergan] or Polytrim [Allergan]) q4-6h. Bandage contact lenses also provide protection between the eyelid and the cornea, and I recommend silicone hydrogel lenses. Begin topical steroid treatment once the corneal lesions have re-epithelialized.

Follow-up these patients on non-steroidal medications one to two weeks after you initiate therapy. Monitor patients who are on other medications very closely for the weeks following the initial diagnosis.

|

|

|

|

Figure 9. Pseudodendrite resulting

from a lens solution

allergy. |

|

Eyelid Interaction

As I mentioned earlier, allergic response and hypersensitivity conditions are not unique to one ocular tissue. Therefore, review the eyelids and the meibomian gland apparatus as they relate to interaction with the aqueous of the lacrimal gland. Tear and meibomian gland assessment is extremely important. Treat the eyelids immediately if there is significant stasis of the meibomian glands, which are usually the inferior glands due to the anti-gravity nature. Manage meibomianitis with microwaved hot packs and lid massages bid to qid for 15 to 20 seconds. Heat is extremely helpful. Topical combination antibiotic/steroid drops following the lid massage for one to two weeks may help resolve acute meibomianitis. Make sure you taper all ocular corticosteroids to prevent a rebound infection. Also differentiate between allergies and other conjunctival abnormalities. You may need to use oral medications to combat chronic meibomianitis. I advise oral tetracycline with a loading dose of 500mg followed by 250mg four times a day for 10 to 30 days. Discontinuing this medication early commonly exacerbates the problem. For doxycycline, use 100mg bid for 10 to 20 days. Other chronic lid abnormalities may require a subtle dosage of 50mg once a day for three to six months for patients who develop internal hordeolums or chalazions associated with meibomianitis and lacrimal gland dysfunction.

Summary

Carefully evaluate an allergy patient's family history, environment and habits. You must then diagnose the allergy while excluding other inflammatory or infectious conditions. Once you make the diagnosis, quickly identify and remove the causative agents to shorten the length of treatment time.

Ocular and systemic medications now help treat this significant condition. Practitioners must warn patients of continual problems and consequences involved with multiple allergy problems. Continuous appropriate follow-up along with preventative and prophylactic hygiene will improve patient comfort. The challenge is there, so get the itch out!

To receive references via fax, call (800) 239-4684 and request document #92. (Have a fax number ready.)