OCULAR DISEASE TREATMENT

Treating Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases in Contact Lens Wearers

A look at using the newest anti-infective and anti-inflammatory medications for treating lens wearers.

By Vishakha Thakrar, OD

Technological advancements in contact lenses have improved the safety of their wear. Nevertheless, infectious and inflammatory events inevitably occur. Fortunately, we've recently added more tools to our armamentarium of medications for combating these conditions.

I'll review these newer medications and how you can use them to fight infectious and inflammatory disease in contact lens wearers.

|

|

|

|

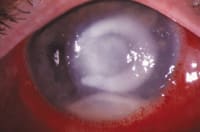

Figure 1. Pseudomonas corneal ulcer |

|

Fighting Infection

Could fourth-generation fluoroquinolones change the means with which we manage microbial infection in our contact lens patients? Traditionally, many of us reserved the "big guns" such as ciprofloxacin HCl (Ciloxan, Alcon) and ofloxacin (Ocuflox, Allergan) for treating infectious keratitis. The reasoning was and still is to use fluoroquinolones only for more severe infections to prevent resistant bacterial strains from emerging. The new generation of fluoroquinolones significantly reduces concerns of resistance propagation while treating a wider spectrum of bacteria than any other topical antibiotic in their class.

Manufacturers created fourth-generation fluoroquinolones -- moxifloxacin HCl ophthalmic solution 0.5% (Vigamox, Alcon) and gatifloxacin 0.3% (Zymar, Allergan) -- to combat fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-positive strains. The second-generation fluoroquinolones were becoming less effective against many Gram-positive bacteria, specifically Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, which cause the majority (approximately 60 percent to 70 percent) of microbial infections. On the other hand, Gram-negative organisms, primarily Pseudomonas, account for the majority of infections in contact lens wearers (Figure 1). Fourth-generation fluoroquinolones have demonstrated a similar effect on Gram-negative species as the second- and third-generation fluoroquinolones, but they're more effective against Gram-positive strains.

Fluoroquinolones act by inhibiting the two enzymes involved in DNA replication: DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. DNA gyrase tends to be the main target in Gram-negative bacteria, whereas topoisomerase IV is the target in Gram-positive organisms. Studies suggest that fourth-generation fluoroquinolones have dual-binding mechanisms, inhibiting both topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase. Therefore, resistance is possible only if a simultaneous double-mutation occurs in the bacterial genes.

This dual-mechanism action likely results from modifications in the fluoroquinolone structure. Clinicians also believe that these chemical modifications:

- Provide anaerobic activity to the fluoroquinolone

- Decrease efflux from the bacterial cell because of the bulky side chain

- Increase the potency of the medication

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) measure in-vitro potency. The antibiotic with the lowest MIC to a microbial group is the most potent. The most potent antibiotic has the least chance of becoming resistant because it kills the bacteria more quickly. Several studies have shown that fourth-generation fluoroquinolones are more potent than their predecessors.

How the New Generation Affects Lens Wear

Fourth-generation fluoroquinolones are currently indicated to treat bacterial conjunctivitis in patients as young as one year of age. Because of their broad spectrum of bactericidal activity, these agents effectively treat more than 80 percent of conjunctivitis. What does this mean for contact lens wearers? The increased potency deters the emergence of resistant strains and enables infections to resolve more quickly. The broad spectrum of coverage ensures a higher probability of completely eliminating microbes. These advantages enable patients to return to lens wear more rapidly.

When choosing between the available fourth-generation fluoroquinolones, you should know the differences between the two. Table 1 summarizes the variations between moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin according to recent studies. In general, topical moxifloxacin will quickly kill the majority of microbial agents associated with contact lens-related bacterial conjunctivitis. In addition, patients will likely comply more because it requires less frequent dosing and has close to neutral pH and lower toxicity.

On the other hand, recall that Gram-negative bacteria cause the majority of contact lens-related infections. One study (Kowalski et al, 2003) demonstrated that ciprofloxacin and gatifloxacin showed more lethal activity toward Gram-negative bacteria than did moxifloxacin. Other studies have demonstrated that statistically, no variation exists in Gram-negative antibacterial activity between second-, third- and fourth-generation fluoroquinolones.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not yet approved fourth-generation fluoroquinolones in treating infectious keratitis (Figure 2) and corneal ulcers. Nevertheless, for some physicians these medications have become the drugs of choice. Studies show that fourth-generation fluoroquinolones demonstrate increased susceptibility to keratitis isolates, both Gram-positive and Gram-negative. Essentially, you must decide if you want to use these agents off-label. Ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin are still effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Because most infections are Pseudomonas-related, we must exercise caution while treating a moderate to severe keratitis in contact lens wearers.

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. Infectious

keratitis |

When choosing whether to use the new fluoroquinolones to treat infectious keratitis, we must evaluate the facts. How does the keratitis present? Where's the location of the epithelial breakdown? Does a history of corneal insult exist? Does this patient wear contact lenses? If so, then does he wear them for daily wear or extended wear? If an ulcer occurs, what is its size and location? Is there an anterior chamber reaction?

If the keratitis is mild to moderate and not sight-threatening, then I would treat the patient with moxifloxacin q.i.d. for one week and schedule a follow-up exam the day after initiating treatment. If I were using gatifloxacin, then I would treat the patient every two hours for the first two days and schedule a follow-up exam after one day, then decrease the dosage to q.i.d. for five days.

If a patient presented with a non-sight threatening ulcer that was less than 2mm in size, then I would treat it with a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone. I would administer a loading dose every 15 minutes for two hours, followed by one drop every one to two hours during the day. At night, the patients would need a broad-spectrum antibiotic ointment. It's imperative that you culture sight-threatening corneal ulcers (Figure 3). At this stage, you may need to abandon fluoroquinolones and use fortified antibiotics such as vancomycin (Vancocin, Eli Lilly) to prevent permanent vision loss.

Fourth-generation fluoroquinolones will become invaluable in treating infectious conjunctivitis and keratitis. However, I think we must use wisdom when treating with these new agents. You can't use these medications against every microorganism. And, as in managing patients with other antibiotics, you must take cultures in certain conditions to initiate appropriate therapy.

|

TABLE 1 Comparing Fourth-Generation Fluoroquinolones |

||

| MOXIFLOXACIN | GATIFLOXACIN | |

| Gram-positive potency | Equal or slightly higher | Equal or slightly lower |

| Gram-negative potency | Equal or slightly lower | Equal or slightly higher |

| pH | 6.8 | 6 |

| Pharmokinetics of kill | Higher | Lower |

| Dosage | t.i.d. x seven days | q. two hours x one to two days, then q.i.d. x five days |

| Preservation | Self-preserved | BAK |

| Toxicity | Equal or slightly lower | Equal or slightly higher |

Treating Inflammatory Conditions

Giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC) (Figure 4) can cause a great deal of discomfort for contact lens patients. We more frequently observe it in our soft contact lens patients, often in those who have soiled or deposited lenses. However, GPC can also occur in patients who are wearing silicone hydrogel and GP contact lenses, often because of a mechanical etiology.

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Severe corneal ulcer |

|

|

|

|

Figure 4. Giant papillary conjunctivitis |

Our choices in treating GPC have increased dramatically over the past few years. We tend to manage our patients based on the frequency and severity of their signs and symptoms. Traditionally, we've treated mild to moderate cases with a temporary cessation of contact lens wear, preservative-free artificial tears, cold compresses, antihistamines, mast-cell stabilizers and combination anti-histamine/mast-cell stabilizers. We reserve topical steroids only for severe presentations of GPC.

Steroids have a profound effect on treating ocular allergies. They suppress or reduce the inflammatory cascade at various stages, thereby blocking the formation of inflammatory mediators. Using these agents to manage ocular allergies is controversial because of the potential for side effects, which include cataract formation, increased intraocular pressure and an elevated susceptibility to infection. Recently, a new study demonstrated that loteprednol etabonate 0.2% ophthalmic suspension (Alrex, Bausch & Lomb) used on a q.d. to q.i.d basis didn't produce the traditional side effects of long-term steroid use. The researchers treated 159 of the 397 patients with loteprednol for greater than 12 months and found no incidence of cataract formation or progression, no clinically significant changes in intraocular pressure and no ocular infection. Other studies, much shorter in duration, provide similar results.

Loteprednol was the first steroid to receive FDA approval for treating seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Its structure is similar to prednisolone acetate (Pred Forte, Allergan), but a slight modification in its composition results in fewer side effects. In addition, it's site-specific, so it becomes relatively inactive before penetrating into the anterior chamber. Research has documented loteprednol as an effective agent in treating GPC. Its recommended dosage is q.i.d. Expect initial relief of symptoms after approximately two hours. Don't use a steroid to treat GPC in patients who wear their contact lenses on an extended wear basis.

Loteprednol's safety and efficacy profile has made it the steroid of choice for treating chronic or severe GPC in contact lens wearers. Combination medications such as olopatadine HCl (Patanol, Alcon) and ketotifen fumarate (Zaditor, CIBA Vision) have proven effective, but at times you may need a steroid to suppress the inflammatory response. You shouldn't make loteprednol your first choice, but it serves as another valuable tool for treating GPC.

|

|

|

|

Figure 5. Atopic

keratoconjunctivitis |

Restasis: Not Just for Dry Eye Allergan released its cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% (Restasis) to treat immune-mediated keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS). Restasis acts by selectively suppressing T-cells. Clinicians had used cyclosporine A to treat ocular inflammatory conditions for several years, but it never became popular because of its toxic effects and irritation. Restasis has alleviated some of the irritation through its 0.05% lipid vehicle. This method of delivery allows this anti-inflammatory medication to penetrate ocular tissues at a much lower concentration. In addition, this agent has no effect on wound healing, cataract formation or intraocular pressure, so practitioners are using Restasis for inflammatory conditions other than KCS.

Many contact lens patients, particularly presbyopes, suffer from dry eye and lens intolerance resulting from blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). This discomfort often results in contact lens drop out. Perry et al (2003) conducted a study on the use of Restasis for treating MGD. Administering Restasis b.i.d. for three months showed a significant decrease in meibomian gland inclusion, telangectasia and corneal staining. Treatment modalities for MGD have always been somewhat limited. As we know too well, patients often don't comply with the regimen of using hot compresses and lid scrubs to treat this condition. Doxycycline and minocycline therapy can prove effective, but we may benefit from adding a topical drop with few side effects to our treatment regimen.

Another indication for Restasis is for treating inflammation in atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) (Figure 5). AKC is associated with atopic dermatitis, eczema, environmental allergies and allergic rhinitis. Its presentation results from both Type I and Type IV hypersensitivity mechanisms. Ocular signs include meibomianitis, ectropion, papillary or follicular reaction, corneal neovascularization, ulceration and scarring. This disease can cause severe visual impairment. Practitioners typically treat chronic ocular inflammation with anti-inflammatories such as corticosteroids, possibly for several years. Unfortunately, treatment of this type isn't independent of steroid-related side effects. Management with Restasis offers a safer means of effectively controlling the disease process. Cyclosporine A acts to decrease the inflammatory process that results in corneal scarring and neovascularization. Similarly, you can use Restasis to treat other atopic diseases such as vernal keratoconjunctivitis.

These are just a few examples of the many off-label indications for Restasis. Its uses will likely become more apparent as we continue to familiarize ourselves with this medication over the next several years.

Helping Patients Continue with Lens Wear

Contact lens patients will continue to present with infectious and inflammatory conditions. However, the advent of new medications and new indications for existing medications will hopefully enable our patients to safely wear contact lenses for many more years.

To obtain references for this article, please visit http://www.clspectrum.com/references.asp and click on document #107.