treatment

plan

AKC

and VKC Require Long-term Strategies

BY

WILLIAM L. MILLER, OD, PHD, FAAO

Although representing less than 3 percent of all allergic conjunctivitis cases, atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) are more severe forms of allergic disease with increasing likelihood with the increasing likelihood of corneal damage and vision loss. AKC and VKC patients can present with bilateral severe itching, thick ropy discharge, conjunctival hyperemia and photophobia. Their chronic and severe clinical presentation will bring about many therapeutic challenges. Demographics and associated systemic signs and symptoms can help you make the correct diagnosis between AKC and VKC.

Signs and Symptoms

|

|

|

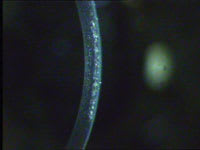

Figure 1. Clinical VKC signs may include large, cobblestone-like papillae. |

Typically, VKC affects males between ages 3 and 20 with most cases manifesting before age 10. Increased prevalence in males decreases with age. New diagnoses of VKC are rare after age 30. Relatively rare in the United States, Canada and Australia, it occurs more in the Mediterranean Sea and West African areas. It tends to be more severe in late spring to summer, but can be present throughout the year. Clinical signs may include large, cobblestone-like papillae (Figure 1), Horner-Trantas dots at the limbus, punctate keratopathy and corneal epithelial shield ulcers.

AKC is typically found in patients ages 20 to 50 with a history or family history of atopic dermatitis or asthma. Common signs are lid eczema, blepharitis, meibomitis, tarsal margin keratinization, conjunctival subepithelial fibrosis, fornix foreshortening, symblepharon formation, giant papillae, corneal SPK, corneal neovascularization and persistent corneal epithelial defects.

Chronic Disease, Treatment

Treatments represent long-term management that often frustrates both you and the patient. You can manage mild forms as you would seasonal allergies (topical antihistamine medications and dual-action medications that contain antihistamine and mast cell stabilizers.) However, you can manage many patients with a pulsed therapy of topical corticosteroids. Because both diseases and treatment are chronic, you must monitor for cataracts and glaucoma development. Common dosage for topical corticosteroids such as dexamethasone 0.1% and prednisolone phosphate 1.0% may be six to eight times a day for seven to 10 days. Newer medications focus on targeting cellular components of conjunctival response. These include the immunosuppressive cyclosporine A and chemokine or cytokine antagonistic agents.

Cyclosporine A is reported to help in AKC and VKC by decreasing interleukin-2 release. Chemokine and cytokine antagonists interrupt up-regulation of other inflammatory factors such as IgE, eosinophils and neutrophils.

You may need to administer additional therapeutic approaches in cases of shield ulcer formation (VKC) or persistent epithelial defects (AKC) where a combination antibiotic/steroid such as loteprednol etabonate and tobramycin ophthalmic suspension (Zylet, [Bausch & Lomb]) or tobramycin 0.3% and dexamethasone 0.1% (Tobradex, [Alcon]) may be useful to reduce ocular symptoms and provide prophylaxis against secondary infections.

Dr. Miller is on the faculty at the University of Houston College of Optometry. He is a member of the American Optometric Association and serves on its Journal Review Board. You can reach him at wmiller@uh.edu.