CORNEAL DISEASE

Managing Inflammatory Corneal Disease

Many corneal conditions do not cause significant symptoms but still require proper testing and treatment.

By Tammy P. Than, MS, OD, FAAO

Dr. Than is a staff optometrist at the Carl Vinson VA Medical Center in Dublin, GA, where she is also the facility's research coordinator. She holds adjunct faculty appointments at UAB School of Optometry and at Mercer University School of Medicine. Dr. Than has published and lectured nationally and has received numerous teaching awards, including the UAB President's Teaching Award in 2004. She was named Young OD of the South in 2006. |

A 58-year-old white male presented complaining of mild foreign body sensation of his left eye that had not resolved despite using his wife's Vigamox (Alcon) for three days. A 43-year-old Asian female presented with slightly blurry vision and eyes that felt a little scratchy. Mild irritation and a three-week history of reduced vision were the presenting symptoms of a 40-year-old black female. A 32-year-old black male presented with slight irritation of his right eye that had been present off and on for several months.

What do these patients have in common? None were current contact lens wearers; all had mild, nonspecific symptoms; and all had corneal diseases. However, each had a very different corneal condition to explain his or her mild symptoms. Final diagnoses for the above patients were respectively: phylectenuolosis, Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis, interstitial keratitis and crack-cocaine keratopathy.

This article will review various etiologies of corneal opacities that often result in only mild symptoms but may require laboratory testing and treatment of underlying systemic disease.

Phylectenulosis

Phylectenulosis is an inflammatory disorder that appears to be a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction (type IV). The term phylcten is derived from the Greek word phlyctaena, which means blister. Phylectenules are generally round, white nodules that may occur on the bulbar conjunctiva or on the cornea; are unilateral or bilateral; may be single or multiple; and are pinpoint to several millimeters in size. Corneal phlyctenules typically originate near the limbus but may migrate more centrally (Figure 1). Vascularization from the conjunctiva accompanies the corneal lesions, and an overlying epithelial defect may exist. Scarring may occur if the lesion is corneal. Scars are typically triangular with the base at the limbus. When the corneal lesions recur they tend to appear at the central edge of pannus from a previous episode and can extend into the central cornea, thus the reference to a "wandering" phylectenule. Patients tend to be more symptomatic if the lesions are corneal and may present with tearing, irritation, photophobia or foreign body sensation. These lesions are associated most frequently with staphylococcal infections and tuberculosis, but have also been noted with Candida albicans, HIV, rosacea, adenoviruses and herpes simplex. Because staphylococcal infections are the primary cause of phylectenules, signs of blepharitis are often present.

Figure 1. Limbal phylectenule. Lesions secondary to staphylococcal blepharitis are usually located inferiorly.

Manage phlyctenules with topical steroids and prophylactic use of a topical antibiotic. Patients may use prednisolone acetate 1% (Pred Forte, Allergan) every two to six hours for one to several weeks. You may combine this treatment with q.i.d. usage of a broad-spectrum topical antibiotic. Tobradex (Alcon) q.i.d. is a good alternative if the presentation is mild to moderate and doesn't require more frequent dosing than q.i.d. These lesions usually resolve within two weeks, although the corneal variant tends to require a longer course of treatment.

To prevent recurrence, it's important to treat the underlying etiology. When associated with blepharitis, lid hygiene is essential and may include warm compresses and lid scrubs or commercially available lid scrubs. In severe cases consider a course of oral doxycycline or minocycline. One combination is minocycline 50mg b.i.d. and SteriLid foaming cleanser (Advanced Vision Research) b.i.d. In the absence of blepharitis, you must consider tuberculosis and order a purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test followed by a chest X-Ray if necessary. Other pertinent laboratory testing such as HIV titre would be indicated based on history and other clinical findings.

Differential Diagnoses Phylectenules resulting from staphylococcal infections are due to a hypersensitivity response. Another corneal manifestation that is an important differential diagnosis would be marginal corneal subepithelial infiltrates. These may be unilateral or bilateral and are often located at 2 o'clock, 4 o'clock, 8 o'clock and 10 o'clock where the eyelid contacts the limbus. These lesions occur peripherally but a clear zone exists between the limbus and the infiltrates. Overlying epithelial breakdown may occur. Mild corneal thinning with superficial vascularization and peripheral scarring may result once the inflammatory response has resolved. Manage these lesions in a similar manner to phylectenulosis secondary to staphylococcal infections.

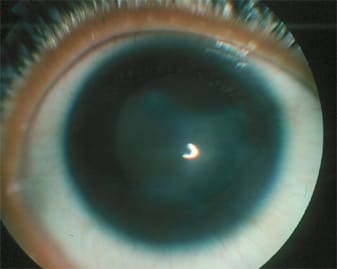

Figure 2. Illustration of white-gray, intraepithelial opacities associated with Thygeson's SPK.

Another important differential diagnosis is Salzmann's Nodular Degeneration (SND), which may have a similar presentation to more established phylectenules. SND was originally considered a dystrophy, but has since been classified as a degenerative change. SND is non-inflammatory, manifesting as a single or multiple elevated, white or gray avascular nodules that are usually located in the mid-periphery. Histologically, the corneal epithelium is thinned with overlying hyalinized collagen. Bowman's membrane is damaged or absent in that area and replaced by basement membrane-like material. These lesions may be unilateral or bilateral and may occur at the edge of a scar (scarring secondary to phylectenulosis).

SND may occur at any age but is more frequent in older patients and more common in women. It may occur following keratitis or chronic ocular surface inflammation, but its occurrence may be years after. It's associated with phlyctenulosis, exposure keratitis, keratitis sicca, interstitial keratitis, vernal keratitis, Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis and rigid contact lens wear. One study showed that 55 percent of SND patients had meibomian gland dysfunction, 33 percent were contact lens wearers and 31 percent had peripheral corneal vascularization.

SND also may occur with no prior corneal disease. There are several case reports of Salzmann's-like nodules developing following LASIK with the hypothesis that decreased tear production, decreased blink rate and Dellen effect may produce enough irritation to induce this corneal degeneration.

Patients may be asymptomatic or present with varying degrees of pain. Vision may be reduced if lesions are located centrally or if nodules induce corneal astigmatism. Patients may also develop recurrent corneal erosions that result in more severe symptoms.

As this condition isn't inflammatory, steroids are of little therapeutic benefit. Conservative treatment may be sufficient and includes lubrication and a bandage contact lens. Nodules may be removed with phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK), lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty or by manual removal.

Figure 3. Stromal infiltration and corneal edema in patient with acute-onset of interstitial keratitis. We found no underlying etiology and this appears to be an idiopathic case.

Thygeson's Superficial Punctate Keratitis

Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) is an epithelial keratitis with periods of exacerbation and remission (Table 1). The lesions usually occur in the central cornea and are small, round or oval, white-gray, intraepithelial opacities that are raised above the normal corneal surface and show minimal staining (Figure 2). Corneal edema and infiltration are usually not present. Essential to making a diagnosis of Thygeson's SPK is the absence of conjunctival inflammation.

These lesions vary in number ranging typically from three to 50. If the lesions do occur peripherally, adjacent corneal vascularization may occur. Up to 50 percent of patients also have subepithelial opacities. Recurrences are common, although the lesions may occur in different areas of the cornea. The condition waxes and wanes for months up to 24 years (average of approximately four years) often with spontaneous resolution. The cornea often appears normal during periods of remission, although mild scarring may result if subepithelial opacities were present. A genetic predisposition to Thygeson's SPK may exist in some patients. Possible etiologies are allergic or viral, but these are controversial. Mild symptoms are expected and include foreign body sensation, photophobia, burning and blurry vision.

During exacerbations, you can treat patients with a variety of therapies based on severity of symptoms. For mild cases, preservative-free artificial tears used every few hours may be adequate. However, for most cases, I recommend a mild topical steroid such as fluorometholone 0.1% (FML, Allergan) or loteprednol 0.5% (Lotemax, Bausch & Lomb) used q.i.d. with an appropriate taper. Consider a bandage contact lens as a long-term solution. Clinical studies using cyclosporine 2% have shown suppression of the epithelial and subepithelial opacities in 72 percent of adult patients as long as therapy was continued, and approximately one-third of patients healed completely with no remission. Although these studies did not evaluate the commercially available cyclosporine 0.05% (Restasis, Allergan), you may consider it in recalcitrant cases or where topical steroids are contraindicated. Topical antiviral therapy (trifluridine) has demonstrated some benefit. The literature cites a patient who underwent PRK for myopia combined with PTK for Thygeson's SPK. No recurrences were documented after the laser procedures, so you may consider them in severe cases. It's essential that you educate patients about the prognosis and that they should expect recurrences.

Interstitial Keratitis

Interstitial keratitis is a nonsuppurative immune-mediated inflammation of the corneal stroma. There is no primary involvement of the corneal epithelium or endothelium. During the acute phase, interstitial keratitis is characterized by areas of dense stromal infiltration, deep stromal neovascularization and corneal edema (Figure 3). These areas appear pinkish because of vascularization and are referred to as the salmon patch of Hutchinson. Patients may have an anterior chamber reaction, fine keratic precipitates and conjunctival injection. In the chronic phase, the vessels regress leaving remnants (ghost vessels). Once the inflammation resolves, corneal thinning and scarring result (Figure 4).

Etiologies include congenital or acquired syphilis, herpetic disease, Lyme disease, chlamydia, Wegener's granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, rheumatoid arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Cogan syndrome, Acanthamoeba, leprosy and idiopathic. Syphilis is the most common cause of bilateral inactive cases. However, the most common cause of active unilateral interstitial keratitis is herpes simplex virus. A significant number of bilateral cases are thought to be idiopathic, which must be a diagnosis of exclusion. During the acute phase, patients often present with complaints of tearing, red eye, and discomfort or pain.

Management during the acute phase includes a cycloplegic agent and a topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% every one to six hours). The acute phase may last for months, requiring topical steroid use for up to two years until the inflammation subsides. Determining the etiology is essential. With such a wide variety of possible causative agents, laboratory testing may include but would not be limited to FTA-ABS, VDRL, PPD, ANA, rheumatoid factor and Lyme titer. If you identify a systemic disease, you should refer patients to the appropriate specialist for treatment.

Despite extensive laboratory testing, we determined that the patient described in the introduction of this article had interstitial keratitis that was idiopathic in nature.

Crack-cocaine Keratopathy

Crack cocaine use is associated with a variety of corneal complications from SPK to ulceration and perforation. These corneal defects from crack cocaine were first described in 1989, and you need to consider the condition in corneal disease with no other etiology. The literature describes corneal infiltrates with overlying epithelial defects, as we saw in the patient described in the introduction. Patients often report rubbing eyes vigorously after crack cocaine use. They may present with periocular or facial burns secondary to homemade crack pipes.

History is important when you find corneal defects of unknown etiology with no other risk factors for such disease. Corneal changes are likely due to toxic effect from the smoke, which is alkaline and results in corneal disruption. The cocaine may also have a direct pharmacologic effect, which results in decreased corneal sensation leading to neurotrophic changes and mechanical effects of vigorous eye rubbing. Corneal sensitivity appears to be decreased with inhaled cocaine as well, and thus ocular complications may occur from that also. Patient compliance and treatment may be difficult. Treat aggressively, especially if infection is present.

When in Doubt

An important differential in all of the above cases is obviously infectious keratitis. Patients who have infectious keratitis typically present with more severe symptoms, lesions tend to be more centrally located and a significant anterior chamber is expected. If in doubt, treat the condition as infectious initially.

Be aware that a wide variety of corneal conditions do not result in significant symptoms but require treatment, laboratory testing and possibly treatment for systemic disease. CLS

For references, please visit www.clspectrum.com/references.asp and click on document #140.

Figure 4. 68-year-old patient with congenital syphilis who developed interstitial keratitis. Photo illustrates chronic phase with dense scarring.