ALLERGY TREATMENT

Treating Allergies in Contact Lens Wearers

Understanding allergy causes and symptoms can help you keep patients wearing their lenses.

By Tracy Bildstein, OD, MS

Dr. Bildstein is a graduate of Southern College of Optometry and received her fellowship in cornea and contact lens at The Ohio State University College of Optometry in 2005. She is currently working at Queens Hospital in New York City. |

As springtime rolls in, so do patients with complaints of itchy, red, watery eyes. Allergic conjunctivitis affects approximately 80 million Americans yearly, or 25 percent of the population. These numbers are more than likely underestimated as many patients self-treat with popular over-the-counter medications and may never have seen an eyecare practitioner for treatment. It's estimated that sales of allergy medications have increased from $6 million to $500 million in the last 30 years.

When treating allergic patients in our clinics, it's important to understand the basics behind the allergic response. There are four types of hypersensitivity reactions that can occur in ocular surfaces. Typical allergic reactions observed in eyecare practice are mediated by type I or type IV hypersensitivity or are a combination of the two.

Type I, or immediate hypersensitivity, is the mechanism behind a typical case of allergic conjunctivitis. When an allergen enters the body it triggers the production of IgE antibodies and sensitizes the body to the allergen. The IgE makes its way to mast cells found in connective tissues, such as the conjunctiva, and attaches to their surface. When the same allergens again enter the body they will bind to the arm of the IgE, causing the mast cells to degranulate, releasing preformed mediators such as histamines. Histamines cause itching by nerve stimulation, vasodilation or redness, and chemosis from increased vascular permeability.

Mast cell degranulation also stimulates the activation of phospholipase A2 to release arachidonic acid (AA). The AA is broken down by two pathways creating prostaglandins and leukotrienes, both inflammatory mediators.

The immune response has two important characteristics.

The immune response is specific. When an allergen sensitizes the body, a specific IgE antibody is produced and only the same allergen will be able to bind to the receptor on the IgE.

The immune response has memory. IgE molecules that bind to the surface of the mast cells remain attached. Upon re-exposure to the allergen it will stimulate the production of more IgE. The allergen will also bind to antibodies already bound to the mast cell, creating a more rapid and larger reaction for each subsequent exposure.

PHOTO COURTESY OF CARLA MACK, OD, FAAO

Figure 1. Dermatitis.

Type II reactions are autoimmune. These reactions occur when tissue-bound antibodies are mediated by the complement system causing the destruction of the tissue. Ocular examples of Type II reactions are Mooren's ulcer and ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP).

Type III reactions occur as a result of circulating complexes composed of antigens bound to antibodies. These complexes deposit in tissue and cause inflammation and cell damage. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and marginal infiltrates are examples of Type III reactions.

Type IV reactions are delayed hypersensitivity or cell-mediated reactions. They are mediated by T cells, macrophages and lymphocytes. Because type IV sensitivities are not mediated by antibodies, the response is not immediate. It may take eight to 48 hours after exposure for the reaction to occur. This mechanism is responsible for contact dermatitis (Figure 1) and plays a role in vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC), atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) and giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC).

Signs and Symptoms of Ocular Allergy

Ocular allergic reactions have many presenting signs and symptoms, and a good patient history is important to make the proper diagnosis. Allergy sufferers typically present with bilateral itching, redness and chemosis of the conjunctiva and/or eyelids.

Excessive tearing with a mucoid component is a common symptomatic complaint. The hallmark symptom of allergy is itching, which must be present to diagnose allergy. If itching is not the most significant symptom reported, consider other conditions such as dry eye, blepharitis or marginal corneal disease.

Seasonal Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC) and Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis (PAC)

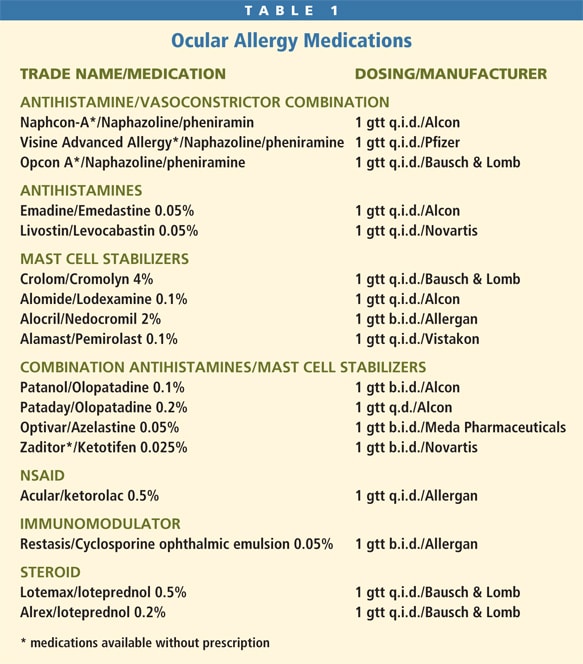

These presentations are commonly grouped together because they are symptomatically similar — although they differ in the time of presentation. Seasonal allergies occur primarily in the warmer months of spring and summer as a reaction to pollens from trees, grasses or weeds. They are predictable, occurring at the same time year after year. PAC is usually a response to indoor allergens such as pet dander, dust mites or mold. Patients with PAC can be symptomatic year-round. The first treatment of SAC/PAC should be to eliminate exposure to the offending allergen. Because this is often not feasible, pharmacological intervention is usually necessary. Table 1 lists the many types of ocular medications, along with their dosing schedules, available to treat allergies.

You can use artificial tears to treat these conditions in mild cases. Artificial tears act to flush the ocular surface and dilute the tear film, decreasing concentration of allergens on the ocular surface. Patients can store artificial tears in the refrigerator to increase the soothing effect of the drops. Use artificial tears in conjunction with a cool compress to reduce chemosis and itching. Educate patients to avoid rubbing the eyes, as mast cells can also release histamine by mechanical stimulation.

Antihistamine drops work by inhibiting or blocking the receptor sites for histamines on the ocular tissues. Several preparations are available over the counter and are combined with vasoconstrictors. The addition of a vasoconstrictor helps reduce redness common with ocular allergy. Avoid using these products to treat ocular allergy for several reasons. First, prolonged use of vasoconstrictors can lead to rebound redness. Second, they are preserved with benzalkonium chloride (BAK), which can be toxic to the corneal surface. Prescription antihistamines without vasoconstrictors are also available, but as with all antihistamines, they provide only short-term relief and must be dosed frequently.

Mast cell stabilizers prevent the degranulation of mast cells and the release of histamine. Start patients on mast cell stabilizers prior to the onset of symptoms as they can take up to four weeks to become effective. Because SAC patients typically exhibit symptoms at the same time of year, starting a mast cell stabilizer a few weeks before allergy season can prevent the onset of symptoms. You can also use this class of medication in combination with other treatments for PAC.

Currently, the most popular medications to treat allergy are the combination formulations. These medications combine an antihistamine, H1 antagonist with a mast cell stabilizer, and are the most successful non-steroidal allergy treatments. These drops are an excellent choice for most types of allergic conjunctivitis, including both SAC and PAC. They're especially useful for contact lens patients because most have twice daily dosing, and patients can use them before lens application and after lens removal.

Olopatadine 0.2% (Pataday, Alcon) may be effective for up to 16 hours of relief with once daily dosing. Ketotifen fumarate (Zaditor, Novartis) is now available as an OTC preparation, which has made this the preferred OTC option.

Consider corticosteroids for severe cases of SAC and PAC. They are effective in treating allergic reactions by preventing the production of arachidonic acid, thus blocking the formation of potent immunomodulators, prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

The goal of steroid treatment with allergy is to quickly reduce symptoms with the shortest course of treatment. A short pulse dose with a rapid taper is often very successful and minimizes the risk of developing side effects such as increased ocular pressure and cataract formation. The steroid medications listed in Table 1 represent "soft steroids," or those that cause fewer side effects than do traditional corticosteroids. Patients should not use their contact lenses while treating with steroids because of the risk of developing infection.

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC)/Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC)

VKC is a chronic bilateral inflammation of the conjunctiva and cornea. It mainly affects children and teenagers, being more predominant in males. Patients are symptomatic in the spring months and will experience VKC over several seasons. Palpebral VKC is characterized by itching, a thick, ropy mucous discharge and large conjunctival papillae on the superior tarsus. (Figure 2) Patients may also report symptoms of photophobia, foreign body sensation, blepharospasm and tearing. Patients with corneal VKC will have shield ulcers, large sterile white infiltrates usually located in the superior cornea, and/or trantas dots, which are white elevated lesions found at the limbus (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Typical presentation of VKC.

AKC is a bilateral inflammation of the eyelids and conjunctiva. It presents in patients ages 30 to 50 and is slightly more common in men than in women. AKC and VKC have a strong association to atopy, which is a genetic condition that predisposes the body to respond to allergens. These patients will show hypersensitivity reactions in parts of their body that are not in contact with the allergen. It's estimated that 5 percent to 20 percent of the general population suffer from atopy and about one-third of these patients will show ocular involvement. AKC presents with signs and symptoms similar to VKC and is more likely to have eyelid involvement. In fact, the hallmark sign of AKC is bilateral swollen eyelids.

Figure 3. Trantas dots in corneal VKC.

AKC can be a severe and chronic condition that leads to many sight-threatening conditions such as corneal scarring and cataract formation. An association has also been suggested between AKC and keratoconus. Chronic eye rubbing may lead to corneal thinning and ectasia.

The most effective treatment to eliminate VKC and AKC is removing the allergen. This would require staying indoors in air conditioning or living in a cool, dry climate. As this is often not feasible, treatment focuses on reducing symptoms.

Corticosteroids are often necessary because of the severity of the symptoms and risk of permanent ocular damage. VKC and AKC are chronic conditions that require a lengthy treatment course; therefore, it's important to minimize the time patients are on steroid medications. One way to reduce a lengthy course is to start treatment with both a steroid and a combination eye drop. The steroid will provide an immediate reduction in symptoms and give the mast cell stabilization mechanism enough time to become effective. After the steroid is discontinued, the combination medication often is sufficient to keep the patient asymptomatic.

Another medication to treat these conditions is an immunomodulating agent, cyclosporine 0.5% ophthalmic emulsion (Restasis, Allergan). While this is a non-FDA approved application, studies have shown it to be effective in reducing the symptoms of VKC and AKC. As there have been no long-term risks associated with its use, Restasis may become a great alternative to steroid treatment in managing chronic allergic conjunctivitis.

Because patients with AKC often have other associated systemic allergic reactions, it's sometimes useful to treat these patients with oral antihistamine medications. These medications will often cause dry eye by reducing tear production, so it's important to supplement treatment with a non-preserved artificial tear.

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis (GPC)

GPC is a hypersensitivity reaction found primarily in contact lens wearers. It also can be caused by an ocular prosthesis and exposed nylon sutures. It's believed that GPC is an allergic reaction to protein deposition on the contact lens surface, and with increased use of more frequently replaced contact lenses, the incidence of GPC has been declining. Soft contact lenses are more likely to cause GPC than are GP lenses. Recently the number of cases has increased among patients wearing 30-day extended wear silicone hydrogel lenses.

GPC presents with symptoms of itching and irritation immediately upon lens removal, mucous discharge, decreased wear time and variable vision due to lens dislocation. Clinical signs of GPC must include giant papillae on the superior conjunctiva, which is observed on slit lamp examination with eyelid eversion. The papillae are generally larger than 0.3mm in diameter and often have a flattened, whitish apex. With soft lens wearers, the papillae (Figure 4) are typically more concentrated at the fold of the tarsus while with GP lenses the greatest concentration is at the lid margin.

Figure 4. Flattened papillae.

The most effective GPC treatment is to remove the offending agent, in this case the contact lens. It may be enough to simply change the contact lens wearing schedule by reducing wear time or changing lens material. Daily disposable lenses eliminate virtually all lens deposits, and you should consider them the lens modality of choice for patients who have a history of GPC. Educate patients on proper lens cleaning and care. Adding a weekly enzymatic cleaner may be effective. Also consider lens cleaning systems that are peroxide-based or otherwise preservative-free.

In a mild case of GPC, the above treatments will most likely be effective and pharmacologic treatment is not necessary. If these treatments aren't effective, intervention with medication is indicated. Patients can use mast cell stabilizers, including combination drops, concurrently with contact lens wear to help relieve symptoms. The combination drops are preferred as they have twice daily dosing and patients can use them 10 minutes prior to lens application and after removal.

More severe cases of GPC require discontinuation of contact lens wear until the signs and symptoms resolve. Steroid use is not usually advocated because of the high risk for contact lens patients to develop infection. Soft lens wearers who are not able to remain symptom-free, even in daily disposable lenses, may require discontinuation of contact lens wear or refitting into a GP lens.

Summary

The large number of individuals suffering from seasonal allergies represents a challenge to every eyecare practitioner. However, such patients rarely represent a contraindication to contact lens wear and, if properly managed, can be long-term successful lens wearers. CLS