KERATOCONUS LENS OPTIONS

Contact Lens Options for Managing Keratoconus

By knowing your options you can meet the goals of a successful contact lens fit and patient satisfaction.

By Nicky Lai, OD, MS, FAAO

Dr. Lai is a clinical assistant professor at The Ohio State University College of Optometry. He is the Chief of Contact Lens Service. |

Keratoconus is a challenge to all clinicians. The primary goals of fitting the keratoconic eye are to achieve good vision, provide patient comfort, and maintain ocular health. The challenge is made easier by having a good understanding of the contact lens options available and by selecting the appropriate lens for your patients' specific needs. Although there may not be consensus among practitioners on the "best" contact lens and fitting method, by following the basic principles and knowing the options, any clinician can meet the goals of a successful contact lens fit and patient satisfaction.

Patient Presentation

Keratoconus is an asymmetric bilateral ectasia, or thinning, of the cornea resulting in increasing steepening of the corneal curvature (Figure 1). Patients who have undiagnosed keratoconus will often present with complaints of blurred or distorted vision that's often uncorrectable with spectacles. Some patients have suffered years of refractive changes and unstable vision.

Figure 1. Keratoconus with steepening of cornea.

Manifest refraction is often unpredictable and may not yield good visual acuity. Based on these initial findings, further testing may help determine the possibility of a corneal ectasia. Retinoscopy often reveals a scissor reflex, and ophthalmoscopy may show an oil droplet appearance to the reflex.

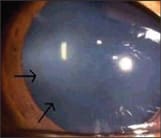

Slit lamp examination may reveal the hallmark clinical signs of keratoconus including Vogt's striae (Figure 2a), Fleischer's ring (Figure 2b), and stromal scarring. Keratometry measurements may be difficult to obtain with distortion in the mires reflecting off an irregular cornea, and reading may also fall outside the range of the keratometry drums.

|

|

| Figure 2a. Vogt's striae. | Figure 2b. Fleischer's ring. |

Automated corneal topography can help show areas of corneal steepening, especially if they are beyond the 3mm area of the keratometer. Topography maps may show an area of increased steepening compared to the rest of the cornea to create an appearance of an "island" of steepening (Figure 3). Be aware that you need to consider a diagnosis of pellucid marginal degeneration if the topography map shows inferior steepening with the "kissing doves" appearance.

Figure 3. Medmont topography axial map of keratoconus with inferior steepening.

Educate patients on the course of the disease including the best options for vision correction, disease progression and potential surgical options.

Soft Lens Options

Once you establish the diagnosis of keratoconus, determining the best lens option will depend on the degree of severity of the disease (Table 1). In some cases the spectacle correction can provide adequate vision, but may be difficult for the patient to wear due to the high refractive astigmatic correction. Soft lenses may be indicated for patients concerned about GP lens adaptation or discomfort.

Specialty spherical soft lenses are available for keratoconus that have center thicknesses of as great as 0.60mm such as the Flexlens Tri-curve Keratoconus design (X-Cel Contacts). The increased center thickness of these lenses attempts to mimic the corneal surface correction of a GP lens with the advantage of soft lens comfort. For patients who have high astigmatism, frequent replacement soft toric lenses such as the Frequency Toric XR or Proclear Toric XR (both from Cooper-Vision) may be available in parameters to adequately correct the astigmatic error.

Because of the steepness of the corneal shape in relation to the rest of the eye, the fit of a soft toric lens may be an issue. When evaluating soft lenses on a keratoconic eye, note centration and movement, but also carefully monitor fluting of the lens edge as this indicates inadequate fit and causes lens rotation and discomfort (Figure 4). Soft toric lenses are also available in custom parameters from other manufacturers to fit the base curve to steep corneas. The Flexlens Toric (X-Cel Contacts) may be considered.

Figure 4. Soft lens edge fluting viewed with fluorescein.

Fitting GP Lenses

When spectacles and soft lenses are inadequate to correct vision, GP lenses should be the next option. There are different considerations when fitting a GP lens on a keratoconic cornea compared to a regular cornea. Because of the variability and irregularity of the cornea in keratoconus, good alignment in one area of the cornea may result in excessive pooling or touch in another area of the cornea. Therefore, fitting strategies in keratoconus need to be a compromise of corneal alignment, corneal touch and corneal clearance.

There are three general approaches to meeting this compromise when selecting the fitting curve. The first is apical clearance, where the base curve of the GP lens is fit steep to completely vault over the apex, or the steepest area, of the cornea (Figure 5). The advantage of apical clearance is that it minimizes any potential disruption of the corneal tissues by avoiding direct contact of the lens to steeper areas of the cornea. The majority of the lens weight will need to rest on the midperipheral and peripheral areas of the cornea. Apical clearance has the potential to decrease the risk of corneal scarring. A disadvantage is that it may cause unstable vision because of the volume of tears necessary to fill the space between the cornea and the lens. There is also the potential for the lens to seal-off on the cornea and interrupt tear exchange.

Figure 5. GP lens with apical clearance with central fluorescein pooling.

A second approach to GP lens fitting is to achieve apical bearing (Figure 6) in which the base curve is fit excessively flat so obvious contact occurs between the lens and apex of the cornea. The weight of the lens is supported by the area on the apex of the cornea but not elsewhere on the cornea. The advantage of this fit is that patients may experience more stable vision as the lens optics rest directly on the cornea. However, as you can imagine, such heavy contact between the lens and the cornea may contribute to increased mechanical epithelial disruption and potential for corneal scarring.

Figure 6. GP lens with apical bearing.

In between these two ends of the fitting spectrum is a lens-to-cornea fitting relationship in which there is very light feather touch on the apex of the cornea and slight touch on the midperiphery of the cornea. This is known as three point touch (Figure 7). The lens rests lightly on the apex of the cornea to provide stable vision. The lens is also supported by the midperipheral cornea to decrease interaction between the apex of the epithelium and the lens. This fit provides good tear exchange while maintaining a more stable and consistent optical surface.

Figure 7. GP lens with three point touch.

The best way to evaluate any of the above lens fitting relationships is by instilling fluorescein via wetted sterile strips onto the bulbar conjunctiva and allowing the tears to carry the dye under the lens. Using a Wratten filter with the cobalt illumination in the slit lamp is the best way to evaluate the fluorescein tear layer under the lens. Areas where there is clearance or space between the lens and the cornea will appear green while areas where there is touch and minimal tear layer will appear dark or almost black.

Also consider lens centration on the cornea. The lens must center on the eye sufficiently to create a regular optical surface over the pupil. The lens will most likely rest at the steepest point on the cornea. In some cases the apex of the cornea is inferior to the pupil, which results in an inferiorly centered lens. A "lid-attached" fit of the lens may be difficult to achieve in this situation.

Be aware that increasing the diameter of the GP lens in an attempt to adequately cover the pupil may create problems with excessive pooling adjacent to the steepest area of the cornea. As the optical zone of the lens becomes larger, more sagittal depth is created under the lens. You can compensate for this using a flatter base curve radius design to maintain the fitting relationship over the apex of the cornea. However, as the optical zone diameter increases, an excessive difference may result between the curvature of the lens that fits the apex but is now too steep for the midperipheral cornea around the "cone." This can result in air bubbles under the lens in the midperipheral area. Air bubbles occur when there is enough space between the lens and the cornea that hydrostatic pressure is not sufficient to create a tear film. Where there is no tear film, the cornea is at risk for desiccation and epithelial damage. As a result of this fitting relationship, spherical GP lenses often have very steep base curve radii with small optical zone diameters. This also creates a tear lens with a steep front surface and high plus power that needs to be compensated for using a high minus lens power.

A way to address the issue of a large optical zone diameter conflicting with curvature changes of a keratoconic cornea is with aspheric back surface curvatures. Aspheric back surfaces result in progressive flattening from lens center to periphery. This idea appears to mimic a keratoconic cornea that has a steep region and becomes flatter and less curved quickly when progressing away from the steep area. A lens with a high eccentricity value will become flatter quicker compared to a spherical curve. This allows you to select a relatively steep base curve radius to match the apex of the cornea while maintaining alignment to areas around the cone with a flatter curvature.

For mild cases of keratoconus, a spherical GP lens with an overall diameter of about 9.5mm may be all that is necessary to achieve good fit and vision. As with all keratoconus GP lens fittings, you can initiate the process by selecting a base curve radius with the average diopter value between the steepest and flattest keratometric reading as provided by corneal topography. The goal is to make sure the back surface of the lens vaults slightly over the apex of the cornea. Because mild keratoconus does not have excessively steep curvatures, a larger optical zone should not create areas of excessive clearance or touch. As the keratoconus progresses, you can steepen the base curve radius with an accompanying decrease of the optical zone diameter. Monitoring fitting criteria such as edge lift, lens centration and lens movement is also important.

Specialty Lenses

As the keratoconus progresses beyond conventional spherical GP lenses, you can employ specialty contact lenses to meet your needs. Specialty keratoconus contact lenses are often available in much steeper base curve radii with smaller diameters to fit the apex of the cone and the midperipheral cornea.

These lenses also use other design elements to enhance fitting. Aspheric back surfaces are used in lenses such as the Rose K2 (Menicon/Blanchard Contact Lens). The Centra-Cone (Blanchard) lens design combines reverse geometry and aspheric curves. The QuadraKone (TruForm Optics) design has separate eccentricities for each quadrant of the lens. The Quad Sym (Lens Dynamics) design has four distinct base curve radii. Some lenses such as the CarterKone (Carter Contact Lens) employ a decentered optical zone to fit over cones that may cause a regular lens to decenter away from the pupil.

Most of these lenses are best fit with a diagnostic lens fitting set because many of the peripheral curve designs are proprietary and specifically designed for a specific base curve radius. Changes in the base curve radius can also change peripheral curves and affect edge lift and lens centration. The biggest advantage is the ease of fit and expert consultation from lens designers and laboratories.

A major problem that can arise is excessive inferior lift-off at the lens edge. Steepening the peripheral curve radii throughout the entire lens to fit the inferior lift-off may cause inadequate edge lift in the remainder of the lens periphery. This can result in poor tear exchange and lens adherence. Designers have developed asymmetric peripheral curves that can be steeper in certain quadrants while maintaining adequate edge lift throughout the rest of the contact lens. Blanchard uses the Asymmetric Corneal Technology design to solve issues of excessive inferior edge clearance; Lens Dynamics uses the Steep/Flat option. The aforementioned QuadraKone is another option.

Larger-diameter corneal GP lenses may solve issues of lens decentration as large lenses tend to center better on the cornea and the optical zone diameters are large enough to cover the pupil. As mentioned previously, fitting these lenses may result in excessive clearance and midperipheral air bubbles. Aspheric back surface curves may help to solve these issues as well.

There is a resurgence in GP contact lenses with diameters that overlap the limbal sclera. These semiscleral lenses completely vault the cornea so the weight of the lens is supported by the sclera. These lenses are especially beneficial in severely irregular corneas.

Piggyback and Hybrid Fits

In some cases the GP lens is fit successfully but the patient can't tolerate it or good centration is impossible to achieve with a GP-only design. This is when to consider a piggyback lens system — a GP lens fit over a soft lens (Figure 8). The soft lens can act as a cushion to the cornea and provides a change in the shape of the cornea to help improve the GP lens fit.

Figure 8. Piggyback lens system with GP lens over soft lens.

The first step to piggyback fitting is to select the appropriate soft lens. The soft lens should be a silicone hydrogel material with a high Dk/t for optimum oxygen transmission as there are now two barriers over the corneal tissue. Select a soft lens with the steepest base curve available such as the Air Optix Night & Day Aqua (CIBA Vision) in the 8.4mm base curve or the PureVision (Bausch & Lomb) in the 8.3mm base curve. The soft lens is still required to drape over the steep keratoconic cornea, so a higher-modulus material may still show some fluting at the edge of the lens. If this is the case, select a lower-modulus lens such as Acuvue Oasys (Vistakon) or Avaira (CooperVision). The soft lens power should not have a large effect on the GP lens power, but may affect the keratometry readings and, therefore, the GP fit. A minus-powered soft lens with a thin center and thicker edge can effectively "flatten" the cornea and may help with fitting a GP lens that has excessive edge lift-off. A plus-powered soft lens with a thicker center may help improve centration of the GP lens over the pupil. Once the soft lens is fitting appropriately, fit the GP lens based on the keratometry readings obtained over the soft lens.

Another option is a hybrid lens with a GP center to correct corneal irregularity. The center is bonded to a soft skirt to help with lens centration and comfort. The SynergEyes (SynergEyes, Inc.) series is manufactured in parameters for normal corneas as well as for keratoconus with steeper base curve radii in the GP and soft skirt. The GP center is Paragon HDS 100 (Paragon Vision Sciences) material.

Conclusion

Fitting a keratoconus patient can be challenging but offers great rewards. These options aren't presented as a progression of lenses throughout the disease, but as a survey of some alternatives. What is successful for one patient may not be to another, so different strategies can increase success. CLS