SCLERAL FITTING TECHNIQUES

Modern Scleral Contact Lens Fitting

Fitting tips to help you succeed with scleral lens fitting and a look at where scleral technology is headed.

By Gregory W. DeNaeyer, OD, FAAO

Dr. DeNaeyer is the clinical director for Arena Eye Surgeons in Columbus, Ohio. His primary interests include specialty contact lenses. He is also a consultant or advisor to MedLens Innovations, Inc. Contact him at gdenaeyer@arenaeyesurgeons.com. |

The popularity of scleral contact lens fitting has risen exponentially over the last five years. Scleral lens lectures, workshops, and posters are now included at most contact lens-related meetings. A few years ago, only a few GP lens manufacturers provided scleral lenses, but now most of the major companies offer their own scleral contact lens designs. This paradigm shift certainly benefits patients who critically need these lenses to correct extreme irregularity or as a therapeutic management device for ocular surface disease (OSD). This article will review basic scleral fitting principles, complications, scleral lens pearls from experts, and future advances in scleral contact lens fitting and design.

Basic Scleral Lens Fitting

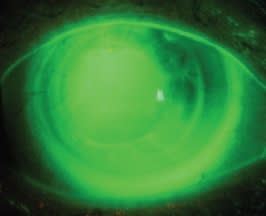

Scleral contact lenses are defined by their size and include GP lenses that fit out onto the sclera. They are grouped under the following categories: corneal-scleral, mini-scleral, and scleral lenses (Table 1). Generally speaking, corneal-scleral designs may share some lens bearing between the sclera and the cornea, while mini-scleral and scleral lens designs distribute all lens bearing on the sclera and completely vault the cornea (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fluorescein pattern of a scleral lens on an eye after a corneal transplant.

Any scleral-type lens should semiseal to the eye without movement, which allows it to hold a fluid reservoir that is able to mask regular and irregular astigmatism. This fluid reservoir, also termed liquid bandage, can therapeutically help patients who have severe OSD by continuously bathing the anterior ocular surface. The larger the diameter, the more reservoir the lens can hold; therefore, scleral lenses that are 18mm or larger are typically more forgiving for extreme irregularity and are more effective when used to manage OSD.

Most practitioners use diagnostic lenses to determine custom parameters; however, as will be discussed later, advances are being made that may allow empirical fitting of scleral lenses based on scleral topography and sagittal depth measurements.

Scleral contact lens fitting philosophy dramatically differs from that of corneal GP contact lens fitting and design. Because of this, new scleral lens fitters who apply corneal GP fundamentals to fitting and troubleshooting scleral lens fits often do not succeed. Is corneal topography needed before starting a scleral contact lens fit? The answer is that it is helpful, but not required. Topography will help determine corneal shape—such as whether the cornea is prolate or oblate—and this will help you to decide whether or not to start with a regular or a reverse geometry diagnostic lens. However, your first diagnostic lens acts as a rudimentary, but effective, topographer and sagittal depth gauge.

Select the initial diagnostic lens based on your gross subjective impression of whether the eye looks steep, flat, or somewhere in between. For example, if you are fitting a patient who has severe keratoconus and a prominent Munson's sign (Figure 2), this eye will most likely need a contact lens with a large overall sagittal depth, so the diagnostic lens that you apply first should be from the steep end of your fitting set. Because tear exchange is slow, add fluorescein to the inside of the lens before application for accurate diagnostic assessment. Corneal-scleral and mini-scleral contact lenses may need to be filled with saline prior to application to avoid air bubbles underneath of the lens; however, scleral contact lenses absolutely require that they be filled with saline prior to lens application.

Figure 2. An 18mm scleral lens on a patient who has extreme keratoconus exhibiting Munson's sign.

Ideal central fluorescein patterns vary with the size of the lens you are using. Well-fit corneal-scleral lenses may have up to 10 to 20 microns of clearance, whereas scleral lenses function best with between 100 and 200 microns of clearance and mini-scleral designs fall in between. Measuring the amount of clearance is easily achieved by turning the slit beam to the side and comparing the reservoir cross-section with the cornea. Allow the best-fitting diagnostic lens to settle on the eye for 20 to 30 minutes. During this time, the lens haptic may settle into the scleral conjunctiva and reduce its effective sagittal depth, which will decrease the amount corneal clearance. If the vault is reduced, order a steeper lens to compensate for the lens settling.

Although corneal-scleral designs share lens support from the cornea and sclera, none of these scleral-type lenses should exhibit limbal bearing, as this may cause damage to the peripheral stem cells that replenish the corneal epithelium. All of these scleraltype contact lenses should rest evenly on the scleral conjunctiva without areas of lift-off or compression (Figure 3). Manipulating the peripheral curves allows you to adjust for an ill-fitting haptic section.

Figure 3. A scleral contact lens demonstrating scleral alignment.

This basic outline does not cover details that apply to specific scleral lens designs, so it is important that you work closely with the manufacturers' fitting consultants during the initial learning curve process.

Advanced Scleral Lens Designs

Occasionally, more advanced design options are needed to improve fit, vision, or both when fitting scleral contact lenses. For instance, a reverse geometry design may be needed to accommodate an oblate cornea after myopic refractive surgery or corneal transplant. In these cases, standard scleral lens designs may exhibit midperipheral touch (Figure 4); however, you can vault this area by making the first peripheral curve relatively steeper than that of the base curve (Figure 5).

Figure 4. A mini-scleral lens showing significant midperipheral bearing on an eye that has undergone a corneal transplant.

Figure 5. A mini-scleral lens with a reverse geometry design shows a significantly improved fit on the same corneal transplant patient shown in Figure 4.

Another advanced option in lens design is to incorporate toric peripheral curves to improve the fit of the lens on the sclera. Modern scleral lenses are generally made of hyper-Dk materials that inherently have some flexure, which allows them to accommodate mild-to-moderate scleral toricity or asymmetry. However, Visser et al (2006, 2007) found in two different studies that patient comfort and wearing time was generally better when patients were switched from back-surface spherical to backsurface toric scleral lens designs.

For patients who have more severe scleral toricity, a back-surface toric lens may be necessary to eliminate lens movement and air bubbles that can form when there is too much of a mismatch between the lens and the sclera. Front-surface toric optics (Figure 6) may be needed to correct for residual astigmatism. Prism ballast, double slab-off, or back-surface toricity can be used to orientate and stabilize a front-surface toric lens. Notches may be beveled out of the lens edge to avoid significant scleral obstacles, such as severe pinguecula or bleb formation after trabeculectomy. Multifocal scleral-type lenses are available, but probably are more appropriate for patients who have a healthy and topographically regular anterior surface.

Figure 6. A front-surface toric scleral contact lens.

Troubleshooting Scleral Complications

Lens Warping A primary reason why patients are not able to reach their vision potential with scleral contact lenses is induced astigmatism secondary to scleral lens warping. Scleral contact lenses are prone to warping on the eye when they are fit on a moderate-to-severely toric or asymmetric sclera. A sphero-cylinder over-refraction will improve the patient's vision, but it will not tell you whether the induced astigmatism is from lens warping or whether it's secondary to internal astigmatism. The key to determining the root cause is to take a keratometry measurement over the scleral contact lens while it is on the patient's eye. If the lens that you are using is spherical, the keratometry reading should be spherical as well. However, if the keratometry reading is astigmatic, then the lens is warping. Increasing the center thickness will prevent this unwanted result. Scleral lenses with diameters greater than 18mm have the greatest tendency for warping because scleral asymmetry increases moving outward from the limbus. Therefore, these lenses should be manufactured with center thicknesses between 0.4mm and 0.6mm for the best optical performance.

Reservoir Debris A well-fit scleral lens that is semi-sealed to the eye will slowly pump in tears to replace its liquid reservoir. Unfortunately, tear debris will also enter the lens chamber, which in some patients is subjectively noticeable and can disrupt their quality of vision. The risk for this complication increases with increasing lens diameter because of increased reservoir capacity and slower tear exchange.

There is significant variation in the amount of debris that builds up underneath the lens among patients depending on lid and tear film differences. Also, some patients are more visually sensitive to the buildup of debris than others are. For symptomatic patients, the only fix is for them to remove their lens so they can rinse and refill it with fresh saline. In a 2007 study, Visser et al found that overall, 48.7 percent of patients wearing scleral lenses (18mm to 25mm) needed one or more of these breaks, and the percentage increased significantly to 66.7 percent for patients who had keratitis sicca. There does not appear to be any fitting change with the lens that can prevent this from occurring. However, having patients fill their lens with a high-viscosity, non-preserved artificial tear rather than with saline may significantly slow down this process. Refitting such patients into a smaller-diameter lens that holds less liquid reservoir and has quicker tear exchange may also be a solution.

Seal-Off/Compression As mentioned previously, scleral contact lenses are designed to rest on the scleral conjunctiva, which allows them to vault over the corneal surface. Because the conjunctiva can be spongy, scleral contact lenses will tend to depress this tissue and may leave an impression ring upon removal that dissipates with time. If there is no associated injection with this impression ring, then it is of no consequence. However, if the contact lens fit exhibits peripheral blanching around the circumference of the lens, then the lens is too tight and has sealed to the eye. In this state, the paralimbal area underneath of the lens will become swollen and injected, and reservoir exchange will cease. A scleral lens that is sealed to the eye can cause extreme discomfort and significantly reduced wearing time. Neovascularization can result if a scleral contact lens that seals is chronically worn. This can be especially dangerous in a patient who has undergone a corneal transplant, as this can increase the likelihood of rejection (Kaufman et al, 1998).

Flattening the peripheral curves is the primary way to return the lens to a semi-sealed state. It is critical that you start flattening the peripheral curve toward the inside of—or central to—the corresponding area in which the blanching is occurring. Starting the flattening too peripherally will lift the lens edge, causing the midperipheral haptic zone to dig further into the sclera and making the seal-off worse (DeNaeyer, 2010). Significant flattening of the peripheral curves will cause the lens to lose some sagittal depth, so steepen the central portion to compensate for this. Fitting back-surface spherical scleral lenses on mildly toric scleras can create some mismatch that will help prevent seal-off. In some cases, even though the fit of the scleral lens haptic is initially ideal, patients may develop chemosis from conjunctival inflammation secondary to a mechanical interaction between the lens and scleral conjunctiva that can cause the lens to fit tighter and eventually seal-off. This inflammatory reaction can occur diurnally, limiting a patient's daily wear time, or it can slowly develop and worsen over months of contact lens wear. If this should occur, try flattening the peripheral curves to reduce lens-to-conjunctival interaction.

Scleral Fitting Pearls From the Experts

Here are some scleral lens pearls from several experts in scleral contact lens fitting:

Dr. Bruce Baldwin "When fitting patients with scleral contact lenses, put the fluorescein directly into the bowl of the diagnostic lens because it will help you to immediately evaluate the fit. However, when evaluating the fit at the dispensing visit, apply the lens using only clear saline. Then apply a generous amount of fluorescein into the inferior cul-desac. Wait and see how long it takes for the fluorescein to uptake underneath of the lens. The landing of the haptic zone on the scleral conjunctiva may look great, but it still might be too tight to allow tear exchange."

Dr. Michael Lipson "When removing a scleral lens, aim the plunger toward the bottom half of the lens. Once the plunger is suctioned on, lift the lens edge away from the eye. Because a scleral contact lens is semi-sealed, there is negative pressure underneath the lens, which can make removal difficult. Lifting the lens edge breaks the seal and releases the pressure, allowing the lens to be easily removed."

Dr. Lynette Johns "When initially fitting patients, don't show them the size of the scleral lens. Seeing these relatively larger-sized contact lenses for the first time may make patients apprehensive and the fitting more difficult. Once you have demonstrated to the patient through diagnostic fitting how comfortable and stable scleral lenses are, they will be much less concerned about how they will apply and remove these lenses."

Dr. Amy Nau "Prescribe a hydrogen peroxidebased cleaning system along with episodic in-office treatment with Progent (Menicon) to keep lenses clean and deposit-free. Have patients fill their lenses before application with non-preserved artificial tears or serum drops, although the latter may cause protein deposition."

Dr. Eef van der Worp "Like the cornea but to a higher degree, the sclera appears to be non-rotationally symmetric in nature. This means that toric or quadrant-specific contact lenses (on the haptic portion of the lens) are indicated in the majority of cases, especially if you go further out on the sclera (e.g. scleral lenses larger than 15mm). The good news is that these contact lenses are very stable on the eye, and front-surface optics (front cylinder and higher-order aberration correction) can be applied to achieve superior visual acuity.

Dr. Christine Sindt: "Mucin can build up under a scleral lens, decreasing comfort and vision. When there is siginficant mucin, patients will complain of discomfort on application. Have the patient dry the contact lens and hold it up to a light source weekly to check for deposits or films that otherwise go unnoticed. If there is a mucous plaque inside the bowl, the most effective way to remove it is with Progent (Menicon)."

The Frontier of Scleral Lens Fitting

There are many changes to look forward to in the use and fitting of scleral contact lenses. One of the most exciting of these is the advancement of sclera measurement and its prospect to improve fitting success. Eef van der Worp, BOptom, PhD, FIACLE, FAAO, FBCLA; Patrick Caroline, FAAO; Tina Graf, BSc; and co-workers at Pacific University have performed preliminary research that has shown some interesting findings about scleral shape and topography based on measurements from anterior segment optical coherence tomography with the Visante OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec) (Bokern et al, 2007; van der Worp and Caroline, 2009).

First, it had been previously assumed that the sclera is curved in shape, but now it is thought to be more tangential relative to the cornea. In addition, it appears that scleral topography can be significantly asymmetric, with the nasal portion having the flattest topography and the inferior quadrant the steepest. The asymmetry increases with increasing distance from the limbal ring. As mentioned previously, a mild mismatch between a scleral lens and the sclera can help prevent seal-off and promote tear exchange. However, if the scleral topography is severely toric or asymmetric, then having the ability to make toric or quadrant-specific lens designs may significantly improve the fit, especially for lenses that have diameters of 18mm or greater.

Advances in anterior segment measurements will soon aid practitioners when fitting scleral lenses. In a 2008 paper, Gemoules demonstrated success using sagittal depth measurements from optical coherence tomography (Visante OCT) to improve scleral contact lens fits in nine patients. The next evolutionary step is to design a profilometer that could measure a complete 360-degree anterior segment contour 20mm in diameter or larger with a single reading. This data could theoretically be sent directly to the manufacturer, which would allow them to empirically design a custom-made scleral lens. Ultimately, more sophisticated scleral data will help improve success rates for complex cases and will reduce the learning curve for novice scleral fitters.

Scleral Lens Education Society

The Scleral Lens Education Society (SLS) (www.sclerallens.org), which was launched in January 2010, is a non-profit organization that is dedicated to teaching practitioners how to fit and use scleral contact lenses in their specialty lens practices. Practitioners who register have access to a library of scleral resources. A special forums page lets practitioners present cases or post scleral lens-related questions to other international participants. Practitioners who successfully meet the requirements of Fellowship will be listed on the Web site as a scleral contact lens fitter, and their practice information will be available to the public. Another aspect of the society is public education and awareness of scleral contact lens applications and availability.

Scleral contact lenses have become an important part of modern specialty lens fitting. Many more patients who have extreme corneal irregularity or OSD are benefitting from these lenses as more practitioners incorporate scleral lens fitting into their contact lens practices. Future advancements in scleral contact lens technology will help to expand their use and success. CLS

For references, please visit www.clspectrum.com/references.asp and click on document #175.