CLS FOR PRE-EXISTING CONDITIONS

Optimizing Lens Wear in Cases of Pre-Existing Ocular Conditions

Fitting contact lenses in cases of pre-existing ocular disease or trauma can improve patients' quality of life.

By John M. Laurent, OD, PhD, & Yin Li, OD, FAAO

|

|

Dr. Laurent received his OD and MS degrees from The Ohio State University and his PhD from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). He completed a residency in Cornea and Contact Lenses at the UAB School of Optometry, where he is currently an associate professor. He has received lecture or authorship honoraria from Alcon. |

|

|

Dr. Li received her BMSc degree from the University of Western Ontario and her OD degree from the University of Waterloo, Canada. She completed her Cornea and Contact Lens residency at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she is currently an assistant professor. |

In some cases, a patient's preexisting ocular disease or condition may make it challenging to achieve a successful contact lens fit. In other cases, the disease or condition may itself be the reason that contact lens fitting is indicated. Regardless of the situation, a combination of expertise and innovation can help you fit these patients with contact lenses.

Ocular conditions that have the potential to interfere with contact lens fitting can involve the eyelids, cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, iris, and lens—almost any part of the eye or adnexa. Disease or injury resulting in an indication for contact lens fitting can likewise involve almost any of these same structures. This article will consider some of these possibilities.

Eyelids/Adnexa

The eyelids are major players in the world of contact lens fitting. The upper eyelids in particular interact with a lens on the eye, being the primary cause of lens movement and having a major influence on lens position.

Trichiasis A category of adnexa problems, often unremarkable for clinicians, involves the eyelashes. Trichiasis, a condition in which misdirected cilia rub against the ocular surface, is usually treated surgically. However, in mild cases, or as a temporary measure, a bandage contact lens can protect the cornea and provide symptomatic relief (Ferreira, 2010; Kirkwood, 2011). Although there are specific lenses that are FDA-approved for use as bandage contact lenses, virtually any lens that covers the part of the eye being rubbed by misdirected cilia should work.

Inflammation Blepharitis, aside from its role as a potential source of ocular pathogens, is primarily a problem for contact lens practitioners in terms of its effect on the tear film. Chronic eyelid inflammation can adversely affect the secretions of the meibomian glands as well as the glands of Zeis and Moll, resulting in ocular surface disease (Weissman, 2008; McCann, 2009). Dry-eye-like tear film deficiencies (secondary to chronic blepharitis or other factors) create a problem with maintaining lens wettability on the eye. Strategies to overcome wettability issues include treating blepharitis or other inflammatory conditions, prescribing rewetting drops, changing lens material, limiting daily lens wearing time, changing contact lens care solutions (perhaps switching to a hydrogen peroxide [H2O2]-based care system), and prescribing daily disposable lenses.

GPC Another inflammatory condition frequently encountered by contact lens practitioners is giant papillary conjunctivitis (GPC). You might consider contact lenses to be contraindicated in patients who have GPC; however, such patients are often contact lens wearers who are unwilling to discontinue lens wear.

The best contact lens option for these patients is daily disposable lenses because the palpebral conjunctiva makes contact with a new, clean lens surface every day (Donshik, 1999; Riley, 2010; Karpecki, 2012). Other measures for managing GPC include a more frequent lens replacement schedule and/or switching to an H2O2 care system.

Ptosis can present a physiological and/or an anatomical challenge to contact lens fitting. The superior portion of the cornea that is significantly covered by the eyelid is usually oxygen-deficient. Frequently, these eyes have corneal neovascularization with blood vessels extending 1mm to 3mm inside the superior limbus, most commonly in the area from 10 o'clock to 2 o'clock.

When fitting an eye that has a ptotic eyelid, use a high-Dk material to maximize the amount of oxygen reaching the cornea. You may want to avoid fitting a corneal GP lens in these cases, as wearing this type of lens may actually cause or exacerbate ptosis. Although the precise mechanism is unknown, repeated lid manipulation with lens removal is a possible cause (Epstein, 1981; Fonn, 1986; Thean, 2004). Consequently, GP contact lens wear (and regular removal) might worsen the condition. Alternatively, there is some evidence that fitting a scleral GP contact lens on a ptotic eye may widen the palpebral aperture and provide some cosmetic improvement (Pullum, 2005).

Lagophthalmos, or incomplete closure of the eyelids, is in effect the opposite of ptosis. It results in some degree of exposure keratitis. In typical cases, slit lamp examination will reveal a small band of superficial punctate keratitis (SPK) near the inferior limbus, corresponding to the area of the cornea not covered by the downward movement of the upper eyelid.

Although lagophthalmos can be a source of discomfort, patients are frequently asymptomatic and unaware of the condition. A common problem for contact lens practitioners is making patients aware of the condition and its potential for causing their contact lenses to dry out and become uncomfortable. Wearing lenses when patients have this condition may also increase their likelihood of developing GPC.

Explain to patients who have lagophthalmos that they may require a shortened daily wear schedule as well as rewetting drops to maintain their comfort. Repeated drying of the front lens surface over the course of the day may also require more frequent lens replacement. To minimize these problems, it would probably be best to fit such patients in daily disposable contact lenses.

Severe lagophthalmos may result in significant exposure keratitis, with 3+ or worse SPK over the lower third of the cornea. These patients are usually very symptomatic, and most will be using artificial tears multiple times a day. Some also sleep with their eyes partially open (nocturnal lagophthalmos) and may awaken with burning and watery eyes (Howitt, 1969). These patients may be successfully fit with scleral contact lenses that will keep their corneas covered by a relatively substantial tear reservoir during the day. Although they will probably still need rewetting drops for their contact lenses, they will avoid the pain and discomfort of exposure keratitis and have clearer, more stable vision. For those patients whose eyes remain open while they sleep, an ointment at bedtime should help, especially if the eyes are no longer dry from daytime exposure.

Case #1 A 37-year-old female who had a history of bilateral congenital ptosis presented to our clinic about five months after undergoing bilateral blepharoplasty. As a result of the surgery, she was suffering from significant lagophthalmos and was using multiple lubricating eye drops and ointment. Slit lamp examination revealed a large area of 3+ SPK inferiorly in both eyes. More notable, however, was her gross appearance: she came into the clinic with her head tilted back, and she was constantly blinking her eyes very rapidly. Her head posture and blinking remained this way throughout the first 30 minutes of the examination.

Although she had not come in for a contact lens fitting, we placed scleral trial lenses on both eyes to see whether they would provide any relief of her symptoms. The patient's head tilt and blinking began subsiding within 15 minutes, and after 30 minutes of trial lens wear, she appeared normal. From our point of view, scleral lenses seemed to be a perfect solution to this patient's problem. However, she did not appear to be as impressed, or possibly she was concerned about handling the lenses. She did not have significant refractive error and did not wear glasses or contact lenses. She said she wanted to discuss the situation with her husband before committing to a contact lens fit. She did not return to the clinic.

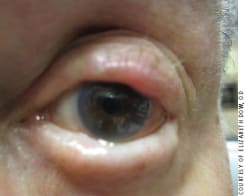

Case #2 A 75-year-old male who had a longstanding history of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and surgery for trichiasis was referred for a bandage contact lens refit on his left eye. He presented wearing a 55-percent-water contact lens that he wore for 30 days continuously and replaced on a quarterly basis. He reported chronic irritation with blinking, even with the contact lens in place.

Refitting him with a high-Dk but low-modulus lens was unsuccessful. It did not relieve his symptoms, and he had difficulty handling the lens. A second lens made of a higher-modulus material (Air Optix Night & Day Aqua [Alcon], MPa 1.4) provided substantial, immediate relief and was easier to handle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A patient who had ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and surgery for trichiasis successfully refit into a high-modulus, silicone hydrogel lens.

Cornea

Corneal disease or injury can be a contraindication for contact lens wear, but there are also a number of such cases in which contact lenses are essential for good vision. These include keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration, some dystrophies, some corneal scars, post-refractive surgery, and some post-graft corneas—any condition that causes optical distortion of the corneal surface (i.e., irregular cornea). Some corneal conditions outside of the irregular cornea category that may involve contact lens fitting include keratitis, corneal abrasion, recurrent corneal erosion, neovascularization, Fuchs' dystrophy, dry eye, and microphthalmia, among others.

Keratitis As contact lens wear can make the cornea more susceptible to disease, it's best to resolve most cases of keratitis prior to contact lens fitting (Silbert, 2000). Infectious keratitis in particular should typically be resolved before fitting a contact lens, as the infection could worsen (e.g., penetrate the stroma if not already involved), and the lenses themselves could become a secondary source of infection. Exceptions would include cases requiring bandage contact lenses such as filamentary keratitis, Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis, or superior limbic keratitis (SLK). In all of these conditions, lens wear could be shortterm (one to two weeks) to cover the cornea during an acute episode of discomfort, or longer-term for patients whose symptoms reappear whenever the bandage lenses are removed or who simply prefer to wear contact lenses (Watson, 2002). In either case, prescribe a lens with a high-Dk material, and both you and the patient need to be vigilant about any acute change in comfort, redness, or light sensitivity as such changes might indicate a corneal ulcer. Three of the four lenses approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be used as bandage lenses are manufactured in high-Dk silicone hydrogel materials: Air Optix Night & Day Aqua, lotrafilcon A, Dk 140; PureVision (Bausch + Lomb [B+L]), balafilcon A, Dk 91; and Acuvue Oasys (Vistakon), senofilcon A, Dk 103) (Thompson, 2013). Other high-Dk lenses could also be used off-label.

Case #3 A 15-year-old male presented with bilateral red eyes and a desire to be fit with contact lenses. He was asymptomatic at that time, but his mother reported that his eyes had been intermittently red for several months, and there were times when his eyes felt "gritty." Slit lamp examination revealed multiple small corneal scars along with some active infiltrates. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/15 OD and OS. He was ultimately diagnosed with Thygeson's superficial punctate keratitis and treated with a short course of topical steroid/antibiotic (Zylet [B+L]).

When his keratitis appeared to be resolved, we fit the patient with Acuvue Advance (Vistakon) contact lenses. Although he experienced additional episodes of redness with new corneal infiltrates, he was usually more comfortable continuing to wear his contact lenses. Over the next five years he had only had one symptomatic red eye episode that required topical steroid treatment. He is currently successfully wearing Acuvue Oasys lenses and has had no red eye episodes in more than a year.

Abrasion and Recurrent Corneal Erosion Bandage contact lenses are frequently used in cases of corneal abrasion and recurrent corneal erosion. If the epithelial defect is large (i.e., greater than 2mm to 3mm) and/or the patient is in significant discomfort, a bandage lens will usually make the patient more comfortable, protect the recovering epithelium from the repeated rubbing of the eyelids, and provide clearer vision. A topical antibiotic, such as moxifloxacin, should be instilled while the contact lens is on the eye at the same intervals that would be prescribed without the lens. We recommend an initial follow-up visit within 24 hours, and thereafter as indicated by the severity of the epithelial defect. The bandage lens may be discontinued when re-epithelialization is complete.

Neovascularization Corneal neovascularization can occur as the result of injury, in which case the area involved would be limited to the injured part of the cornea extended to the limbus. Corneal neovascularization can also result from hypoxia, in which case blood vessels may extend 2mm to 4mm into the cornea around the entire limbus. A frequent cause of hypoxia is a contact lens that is very thick and/or manufactured in a low-Dk material.

Using the very high-Dk materials that are available today, you should be able to fit most corneas that have neovascularization. Several GP and soft lenses have Dk/t values greater than 100.

In a case of neovascularization post-injury, follow patients closely for several months after contact lens fitting to make sure that the neovascularized area is stable and not getting worse. With neovascularization from hypoxia, typically patients initially present with low-Dk lenses that they may be wearing overnight as well. After being refit with a higher-Dk material and/ or discontinuing overnight wear, the neovascularization frequently disappears entirely, although ghost vessels may remain that could refill with blood if the cornea is again compromised with hypoxia or some inflammatory condition.

Case #4 A 44-year-old male who had keratoconus wore a GP scleral lens on one eye and a soft lens on the other. He presented for a routine examination and wanted a new scleral lens, as he had lost his most recent one "sometime" in the previous year. The scleral lens he was wearing was an extra one from several years earlier. Fluorescein instilled in the eye did not penetrate under the lens, and there was corneal bearing inside the limbus 360 degrees. There was also corneal neovascularization 2mm to 3mm inside the limbus 360 degrees. The contact lens material had a respectable Dk of 97 (Tyro 97 [Lagado]), but the lens was fairly thick (0.4mm to 0.5mm) and resulted in a hypoxic environment.

We refit the patient with a new scleral lens made from Boston XO2 (B+L), Dk = 142. There was no corneal bearing with the new lens, instilled fluorescein readily penetrated under the lens, and there was no visible neovascularization after wearing the new lens for six weeks.

Fuchs' Dystrophy As Fuchs' dystrophy compromises the corneal endothelium, the layer of cells most responsible for maintaining the relative dehydration of the corneal stroma, corneal edema is a common problem for patients who have this condition. Corneal bullae, which can occur in the more advanced stages of Fuchs' dystrophy, may cause enough discomfort to indicate fitting these eyes with bandage contact lenses.

A primary consideration in fitting a Fuchs' Dystrophy patient with contact lenses is to minimize physiological compromise, i.e., use a lens with a high Dk/t. Air Optix Night & Day Aqua (Alcon), Dk 140; Biofinity (Cooper-Vision), Dk 128; and Dailies Total1 (Alcon), Dk 140, would all be good choices. Overnight wear should be avoided.

Microphthalmia, or abnormally small eyes, may be unilateral. If so, patients might benefit from a prosthetic contact lens on the smaller eye that matches the appearance of the normal eye. Fitting contact lenses in cases of bilateral microphthalmia is very much like fitting a juvenile eye. Even though the eyes are smaller, keratometry measurements may be normal, and you may be able to fit these patients with standard lenses, either soft or GP.

Conjunctiva

Pinguecula and Pterygium Conjunctival irregularities such as pinguecula and pterygium can present unique challenges in contact lens fittings. Pingueculae are usually more severe and have an earlier onset in contact lens wearers compared to in non-wearers, and they tend to be more significant in GP lens wearers than in soft lens wearers (Mimura, 2010). Soft lenses are often large enough to cover most of a pinguecula without causing significant rubbing, whereas the firm edges of GP lenses can exacerbate severe chronic stimulation of the conjunctiva and any early pinguecula that exist (Mimura, 2010). On a positive note, UV-blocking soft contact lenses can provide limbal/conjunctival protection against UV radiation, which is believed to be the primary cause of pingueculae (Mimura, 2010).

Another modality to consider is scleral contact lenses, in which the lens periphery may cover most of a pinguecula and, without significant movement, may be neutral in terms of lens-pinguecula interaction. It is also possible to have a notch cut into the edge of a scleral lens to accommodate an elevated lesion on the conjunctiva (Figure 2). In cases of acute pingueculitis, it may be necessary to temporarily discontinue contact lens wear until the inflammation is resolved, using topical steroids when/as needed.

Figure 2a. A scleral lens with a notch.

Figure 2b. The notched scleral lens fitted successfully on a glaucoma patient who had a filtering bleb.

A pterygium, depending on size, location, and degree of stability, is probably a more serious obstacle to contact lens fitting compared to a pinguecula. If there is significant growth inside the limbus, avoid a corneal GP lens because the edge would most likely serve as a chronic irritant to the proliferating edge of the pterygium. Soft, scleral, and hybrid lenses are possibilities, but would initially require frequent monitoring. Any lens that increases inflammation or pterygium growth onto the cornea should probably be discontinued. A large pterygium may cause changes in astigmatism and corneal irregularity, which may necessitate changes in contact lenses and/or surgical intervention in severe cases (Maheshwari, 2007).

Acute conjunctivitis, regardless of etiology, is best treated and resolved before contact lens fitting or while suspending lens wear. In cases in which contact lens wear is necessary in spite of the conjunctivitis, corneal GP lenses or daily disposable soft lenses could be worn with caution. It may also be best to use GP contact lenses or daily disposable contact lenses in cases of chronic conjunctivitis that require the use of topical medications to minimize the absorption of any drug and to avoid creating a habitat for microorganisms. Fitting contact lenses on eyes that have conjunctival disease always requires you to thoroughly educate patients about the importance of compliance, as well as the signs and symptoms that require a return to clinic.

Iris

Pupil Abnormalities Iris abnormalities can cause cosmetic and vision problems, both of which may be corrected with contact lenses. An ectopic pupil can be cosmetically corrected using an opaque tinted contact lens with an opaque black pupil, but doing so would sacrifice any vision provided by the ectopic pupil. In the case of aniridia or severe iridodialysis in which the pupil is essentially absent, an opaque tinted contact lens with a clear artificial pupil could substantially improve vision.

Improving Cosmesis When the iris is discolored or cosmetically disfigured, a tinted contact lens for improving its appearance does not necessarily have to block vision—in some cases, it may improve it. A relatively simple solution for any cosmetic correction would be to try standard opaque tinted lenses, such as FreshLook Colors (Alcon), to determine whether the appearance and/or vision are acceptable. If not, consider a custom prosthetic lens with a clear or occluded pupil as needed for the affected eye.

Case #5 A 28-year-old female who had a history of albinism was referred to our contact lens clinic by the University's Low Vision Clinic. BCVA was 20/200 OD and OS. Refractive error was negligible. The lack of iris pigment in her eyes meant that her irides did not occlude light, and her pupils were not really functional. The patient had never worn contact lenses, and we hoped that an occluder contact lens with an artificial pupil might improve her vision. She was also interested in having her eyes appear to be a more solid shade of blue rather than the pink-gray color that they were naturally.

We ordered custom prosthetic soft contact lenses with a medium blue tint, a black underprint to block the light, and 4mm clear pupils. While the lenses made her eyes look blue, there was no subjective improvement in her vision indoors and no measurable change in VA. However, she did notice a subjective improvement in her vision when walking outside in the sunlight. She still needed her sunglasses, but felt that she could see better with the contact lenses. The patient could wear the lenses comfortably for 12 hours daily and felt that it was worthwhile to wear them for cosmetic reasons indoors with a little visual improvement outdoors.

Case #6 A 39-year-old female who had a history of heterochromia secondary to recurrent iritis in her right eye came to the clinic to see whether a tinted contact lens could make her eyes look more alike. Her right eye was lighter in color and slightly more mottled in appearance compared to the left eye. A series of diagnostic lenses determined that the best solution was translucent, "enhancer" tinted lenses in which the color of the tint combined with her iris color. The right eye was fit with a dark blue enhancer tinted lens and the left eye with a lighter color. The result was not a perfect match between the eyes, but it was much closer and the dark blue tint reduced the mottled appearance of the right eye. The patient was satisfied enough to wear the lenses.

Case #7 A 53-year-old female who had a history of injury and scarring in her right eye presented to the clinic with a patch over her right eye. Her tinted contact lens had faded to the point that it no longer helped her to wear it. Examination revealed a large corneal scar on the right eye with a severely torn iris, mostly removed by surgery, and crystalline lens extraction without an intraocular lens (IOL). Unaided VA was light perception (LP) OD, 20/30 OS. BCVA was 20/60 OD (with + 14.50 -1.00 × 040) and 20/20 OS.

The contact lens that the patient had been wearing had a light-blocking opaque tint with an artificial black, occluding pupil. Although she was correctable to 20/60 in her right eye and could have had a correction incorporated into a new lens with a clear pupil, she did not like the result. The distorted vision in her right eye interfered with the vision in her left eye to the extent that she preferred occlusion of the right eye. We refit a custom soft prosthetic lens (Orion Vision Group) with an opaque tint and black pupil that provided a close cosmetic match to her left eye (Figure 3). We ordered it with a gray underprint rather than black, but she reported that even the small amount of light coming through the gray underprint interfered with her vision when she was outdoors in sunlight. She is scheduled to be refit with a new opaque lens with a black underprint.

Figure 3a. Patient who has a scarred cornea without a contact lens.

Figure 3b. Same patient after being refit with a prosthetic soft lens.

Crystalline Lens

Frequent shifts in refractive error in cataract patients might be more easily and inexpensively resolved with a simple change in contact lens power compared to reordering new spectacle lenses, especially for a patient who has progressive addition lenses. If the refractive change is significantly greater in one eye, resulting in anisometropia, contact lens correction can minimize the difference in magnification between the eyes and possibly help prevent aniseikonia (Benjamin, 2007).

Aphakia Depending on the prescription required, quite a number of contact lens choices are available for aphakic patients. Most GP manufacturers make lenses in powers that are suitable for aphakic patients. However, aside from the customary awareness issues that may occur with corneal GP contact lenses, the high plus power of aphakic lenses can cause the center of gravity to shift anteriorly and may cause the lens to decenter inferiorly. In some cases, a lid-attached fit may be achieved; i.e., the upper eyelid may be able to help center a minus-carrier lenticular contact lens design on the cornea.

Another potential issue with high-powered plus lenses is oxygen transmissibility, which could be limited by lens thickness. Using a lens material with a Dk of 100 or more should help prevent any problems with corneal hypoxia.

Soft contact lenses, with their superior initial comfort and easier-to-achieve centration, are probably the most preferred choice for an aphakic fitting. A number of hydrogel contact lenses that have material Dk values as high as 33 are available in powers up to +20.00D, with some as high as +50.00D. A relatively new silicone hydrogel material (Definitive [Contamac], efrofilcon A) with a Dk of 60 is available in powers greater than +20.00D and can be ordered in a toric or toric multifocal design.

Case #8 A 22-year-old male had a history of bilateral congenital cataracts and underwent cataract extraction at age 3 months. He also had mild microphthalmos with a horizontal visible iris diameter of 9.5mm (Figure 4). He presented wearing an unknown brand of soft contact lenses and wore reading glasses over them for near work. He felt that his vision was slightly reduced, more so in his left eye. Initial findings were as follows:

Figure 4. A patient who has microphthalmos.

His VA (with his current contact lenses) was OD 20/50+2 and OS 20/200-1. Slit lamp examination revealed corneal neovascularization extending 2mm to 3mm 360 degrees inside the limbus, OD and OS. There were several faint, peripheral corneal scars OD and OS. There was no fluorescein staining. The patient's refraction was OD +20.50 sphere, 20/40 and OS +19.50 -0.25 × 005, 20/50+2. His keratometry readings were 44.50 OD and 46.50 OS.

Because of the neovascularization and evidence of previous infiltrative events, we refit the patient with Silsoft (B+L) lenses (Dk 340). Although his vision was greatly improved with these lenses, he developed a midperipheral corneal ulcer in his left eye.

After treatment and resolution of the ulcer, he was refit in custom multifocal contact lenses (Intelliwave Multifocal [Art Optical]) made with efrofilcon A (Dk 60). The patient experienced better vision and comfort with these lenses than he had with any of his previous contact lenses. The final lenses had parameters of OD 8.5mm base curve, 14.0mm diameter, +25.00D power with a +2.25D add, 20/40+2 and OS 8.5mm base curve, 14.0mm diameter, +22.00D power with a +2.25D add, 20/40. He wore these lenses 14 to 15 hours daily, and his near vision was 0.75M (20/40+) without the need for reading glasses. On follow up there were no visible signs of corneal neovascularization in either eye. The lenses were prescribed for quarterly replacement.

Case #9 A 59-year-old female who had a history of bilateral LASIK refractive surgery and subsequent cataract surgery (with IOLs) presented with a primary complaint of reduced vision that was not improved with glasses or soft contact lenses. She also had a longstanding history of dry eye.

Her VA (unaided) was OD 20/40-1 and OS 20/80-1. Her refraction was OD Plano -0.75 × 180, 20/40 and OS +1.75 -0.50 × 035, 20/40. Slit lamp examination revealed clear corneas with no staining OD and OS. The IOLs were clear and centered.

Our initial impression was that the patient's reduced vision was probably due to irregular corneas exacerbated by her dry eye condition. Topography revealed central flattening characteristic of corneal refractive surgery. We chose scleral lenses for a diagnostic fitting because they are indicated for both dry eye and irregular cornea. Unexpectedly, VA with the diagnostic lenses and a spherical over-refraction (OR) was worse compared to the VA with spectacles. However, the following spherocylindrical OR resulted in very good vision: OD Plano -1.00 × 090, 20/20+1 and OS -0.50 -0.75 × 080, 20/20.

We felt that the patient's reduced vision was due to a combination of irregular cornea and residual lenticular astigmatism from tilted IOLs (Korynta, 1999). Without irregular corneas, a spectacle prescription should have been able to correct the resultant astigmatism (cornea + tilted IOL) and provide satisfactory vision. Without tilted IOLs, a spherical GP contact lens should have corrected the corneal astigmatism and provided satisfactory vision.

The patient was ultimately fit with front-surface toric scleral lenses that corrected both the irregular corneal distortion and the residual astigmatism. With her contact lenses, VA was 20/20 OD and 20/20- OS.

Making a Difference

Fitting contact lenses on patients who have pre-existing ocular disease can be challenging and, in some cases, is like stepping into "uncharted territory." However, many of these cases provide us an opportunity to make a significant difference in someone's life, which can be very rewarding. Also, establishing a reputation for fitting patients who have unique or difficult conditions can be a great practice-builder. Welcome these patients into your practice. CLS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Elizabeth Dow for her case study and photo as well as Dr. Gregory DeNaeyer for his photos.

To obtain references for this article, please visit http://www.clspectrum.com/references.asp and click on document #217.