Prescribing for Astigmatism

Signs of Irregular Astigmatism

By Thomas G. Quinn, OD, MS, FAAO

Over the years I’ve seen many patients present with visual complaints secondary to corneal irregularity induced by conditions such as keratoconus. Remarkably, many of them were not aware that they had anything more than “astigmatism.” What can tip us off that a patient has something more?

Recognizing the Signs

Patients who have both regular and irregular astigmatism may complain of blur as well as headaches and double vision. The double vision is not true binocular diplopia. Rather, it results from large differences between major meridians. The major meridians are 90 degrees apart in those who have regular astigmatism. Those who have irregular astigmatism have major meridians that are separated at some other angle. In either case, a secondary “shadow” image may be reported. This can easily be distinguished from true binocular diplopia by covering one eye to see whether the “diplopia” disappears. In the case of high astigmatism, either regular or irregular, double vision will continue to be reported under monocular conditions.

Although regular and irregular astigmats can have some similar symptoms, others can tip you off that more is going on.

Patients who have irregular astigmatism secondary to keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD) will manifest refractive shifts that are more significant than what you might normally experience with other patients. Although it might not be unusual to see shifts of up to 1.00D in myopia, especially for early adolescents, annual shifts in astigmatism of this amount are unusual in the absence of disease. In particular, patients who have PMD can have remarkably high against-the-rule astigmatism (Jinabhai et al, 2011).

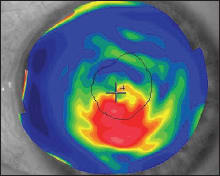

Figure 1. Corneal topographic map of keratoconus.

Age of onset can be another indicator of something unusual. According to the National Keratoconus Foundation, “Keratoconus is generally first diagnosed in young people at puberty or in their late teens.” That said, keratoconus has been documented to have onset in at least one case after age 50 (Tenkman et al, 2012). PMD generally onsets between the second and fifth decades of life (Jinabhai et al, 2011).

Family history can serve as another indicator that further investigation is warranted, as keratoconus can have a genetic link (Tuft et al 2012).

Another “red flag” that should prompt more thorough investigation is a hard-to-pin-down, or “soft,” refractive endpoint. Some patients simply aren’t very good observers, but others struggle because the optical system is compromised due to corneal disease.

These same optical defects will often result in a somewhat reduced best-corrected acuity. So, if you aren’t able to achieve the kind of vision you’d expect, look at the optical systems, including corneal integrity.

Confirming Suspicions

Once you suspect corneal irregularity, you can confirm its presence by observing the red reflex, either with retinoscopy or ophthalmoscopy. Looking for distortion in keratometry mires can also be helpful. However, topography is probably the best way to identify not only the presence of corneal irregularity, but also its size, location and degree of severity (Figure 1). CLS

For references, please visit www.clspectrum.com/references.asp and click on document #207.

Dr. Quinn is in group practice in Athens, Ohio. He is an advisor to the GP Lens Institute and an area manager for Vision Source. He is an advisor or consultant to Alcon and B+L, has received research funding from Alcon, AMO, Allergan, and B+L, and has received lecture or authorship honoraria from Alcon, B+L, CooperVision, GPLI, SynergEyes, and STAPLE program. You can reach him at tgquinn5@gmail.com.