Improving quality of life with contact lenses for patients suffering from debilitating corneal conditions can be impactful and rewarding for both patients and practitioners. Patients who have corneal irregularity, scarring, dystrophies, ectasia, and other pathologies are often unable to obtain normal vision with eyeglasses or standard contact lenses. Many cannot recognize faces, drive, work, read, learn, prepare food, ambulate, or live independently because of their vision impairment. The direct and indirect costs to society are significant for this population. For these patients, contact lenses are not simply an elective or cosmetic option—they are often the only means to restore vision and are medically indicated to bring visual functioning to a normal or near-normal level.

Numerous articles, webinars, and other resources are available that describe how to fit all types of contact lenses for patients who have corneal and ocular surface diseases and conditions that require medically necessary lenses. The Gas Permeable Lens Institute (GPLI) web site (www.gpli.info ) may be the best overall resource for practitioners, students, and residents. Excellent articles from Contact Lens Spectrum and other publications are archived online and are easily accessible. Therefore, rather than serve as another “how to” guide, this article will share my philosophy and clinical care process used at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Optometry Cornea and Contact Lens Service. This may help those wishing to add medically necessary lens care to their practice or provide a different perspective for those already providing this service.

WHAT ARE MEDICALLY NECESSARY CONTACT LENSES?

Medically necessary contact lenses (MNCLs) restore visual function in patients who have ocular pathology when standard spectacle or contact lens correction does not provide satisfactory visual improvement. The ocular pathology can be any condition that produces a distorted/irregular, dysfunctional, or scarred ocular surface. The well-known major indications include keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration, post-surgical ectasia, corneal scarring, corneal degenerations and dystrophies, and severe dry eye disease. The common denominator with most of these conditions is irregular corneal astigmatism, which can vary in presentation from mild to severe. Other indications include patients who have high or extreme refractive errors, significant anisometropia, facial defects that preclude spectacle wear, diplopia or multiple images (monocular or binocular), photophobia, or other conditions limiting visual quality or acuity.

Although corneal and scleral GP lenses make up the majority of MNCLs, any lens material or modality may serve as a medically necessary lens. MNCLs are not limited to corneal or scleral GP lenses and, in fact, some patients achieve a successful outcome only with soft or hybrid lens designs. Some patients who have asymmetric or unilateral pathology may do well with a different lens design on each eye or even with a unilateral contact lens.

UNDERSTANDING AND EDUCATING PATIENTS

Practitioners and staff should understand that the clinical context for patients who need MNCLs is different than for normal or elective contact lens patients. These patients have been diagnosed with a medical eye condition related to disease, injury, or surgery that has decreased their best-corrected visual acuity and/or the visual quality in one or both eyes. Some may have a recent diagnosis, while others may have suffered for years and have been evaluated by multiple practitioners. If the visual impairment is moderate or severe bilaterally, the patients are likely to be handicapped with regard to activities of daily living and are likely to be functionally disabled. These patients may use or may have tried optical and non-optical low-vision devices with varying degrees of success. As with other low-vision patients, these patients may have unrealistic positive or negative expectations based on their previous experience with optometrists, ophthalmologists, or other professionals.

If a patient is new to the practice, there will likely be anxiety and concerns about the practitioner and staff, the time and effort required, costs and insurance coverage, and other details. For patients who have no previous contact lens experience, they may be afraid or hesitant to touch their eye or to manipulate a contact lens. If contact lenses were used previously, there is typically less apprehension about trying a different lens design that may improve their vision. Practitioners and staff members must be sensitive to this backdrop and carefully communicate the objectives and expectations for each visit.

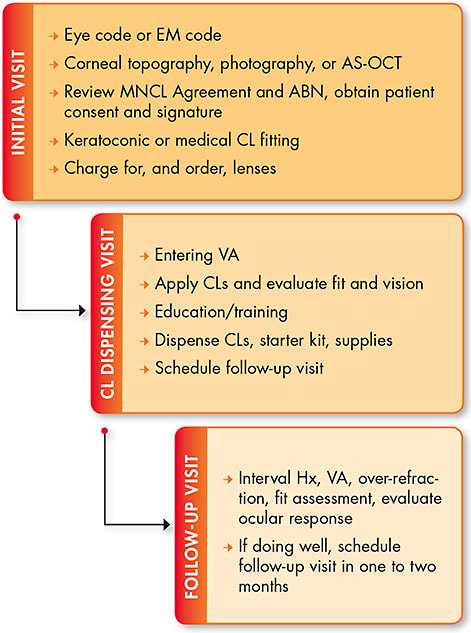

The process of managing a patient with MNCLs typically involves multiple visits over weeks or months (Figure 1) and may require significant out-of-pocket expenses. A handout or brochure combined with online resources can be very helpful to patients, family members, and potential referral sources in the community. An example brochure on MNCLs by Dr. Clarke Newman is available on the GPLI website (www.gpli.info/pdf/2013-sample-bro-medically-necessary.pdf ). Insurance information, eligibility, benefits, deductibles, copayments, and noncovered or out-of-pocket costs should be reviewed and explained to patients prior to the initial visit, if possible. An Advance Beneficiary Notice (ABN) form can be used to inform and explain fees and charges for office visits, specialized testing, fitting fees, contact lens materials, and follow-up visits. Use of an ABN form ensures that patients understand the nature and complexity of the care process for MNCLs as well as their financial responsibility. The office policy on payment mechanisms, product warranties, refunds, and credits should also be communicated to and acknowledged by patients.

INITIAL VISIT

The initial visit will typically entail reviewing referral information (if applicable) or previous examination results. A focused history should include the chief complaint and history of present illness that documents the patients’ perception of their condition, visual symptoms, functional impairment, and previous treatments including contact lenses, medications, and surgeries. The past medical history, current medications, and allergies to medications and environmental stimuli may be relevant and should be documented. Patients who have corneal and/or ocular surface disease, and those who have corneal transplants, are typically using multiple prescription and over-the-counter drops on a long-term basis.

Initial Evaluation Measure entering visual acuity (VA) with and without habitual spectacle or contact lens correction. Improved acuity with pinhole vision testing is generally a positive prognostic sign for vision improvement with MNCLs. Near vision and the preferred reading or working distance are also important to document, regardless of patient age. Encourage patients to hold the reading card at whatever distance provides the best reading ability. Patients who have corneal ectasia will often demonstrate an extremely close reading distance corresponding to a highly myopic far point position.

A refraction should be attempted to document the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) with conventional spectacle correction; this is often required by insurance plans. The starting point may be an auto-refraction, retinoscopy, or the habitual prescription. Refraction is often unproductive in patients who have moderate or advanced pathology, so this should be performed quickly and efficiently. For patients who have severely decreased vision, perform the refraction using large spherical changes (with ±3.00D steps), and 2.00D to 4.00D of astigmatism can be introduced and rotated in the phoropter or trial frame. Understand that the intent is not to prescribe glasses but to document the BCVA with refraction as well as the extreme refractive error often resulting from corneal ectasia, scarring, or surgery. In many cases, refractive testing provides no improvement in BCVA, and this should be noted.

Consider the following quick test to assess the quality of vision and the severity of higher-order aberrations. With the room as dark as possible, ask patients to view a transilluminator with the right eye (left eye covered) and to describe the appearance of the light. Is there distortion, fuzz, halos, or streaks around the light? Then repeat the test while the patient views with the left eye for comparison. This simple technique provides an assessment of the quality of vision in each eye under large-pupil conditions, which simulates driving at night. I call this test the “poor man’s aberrometer.”

The next step is a careful slit lamp examination of both eyes. The presence of meibomian gland disease, blepharitis, pingueculae, and other conjunctival lesions should be noted. Examine the cornea for scarring, thinning, edema/haze/cloudiness, neovascularization, elevation or depression, incision and suture tracks, laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) flaps, corneal graft, interrupted or continuous sutures, intrastromal ring segments, inflammation, pigmentation, or other significant abnormalities. It is important to document the baseline condition of the cornea and ocular surface before contact lenses are applied or dispensed.

Specialized testing such as corneal topography, anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT), pachymetry, specular microscopy, and/or photodocumentation may be performed if medically indicated. The horizontal visible iris diameter (HVID) can also be measured prior to initial lens selection and application.

I also perform an “eyelid manipulation test” to help gauge which lens design to try first and a patient’s level of apprehension. While the patient looks straight ahead, retract both lower lids and then both upper lids. If the patient is fairly relaxed and cooperative, then I would consider a scleral lens first if indicated. If the patient appears anxious, squeezes the lids shut, or backs away, then I may start with a soft lens. This maneuver also lets me assess the size of the palpebral apertures, the tightness of the lids, and whether the eyes are deep set.

Lens Selection and Fitting The next step is to select and apply diagnostic lenses, allow for initial settling, and evaluate the fit. Choose the initial lens type and design based on the assessment of the patient history and exam results. At UAB, the initial lens is typically a scleral lens due to the stability, comfort, and vaulting characteristics, which protect and hydrate the cornea and limbus without bearing, friction, or pressure. The diagnostic scleral lens bowl is filled completely with nonpreserved sterile saline mixed with a fluorescein strip prior to application. Once the lens is applied, use a transilluminator or penlight to look for large bubbles. If any large bubbles are present, remove and reapply the lens. A persistent, large central bubble indicates excessive vault, and a flatter base curve (2.00D to 3.00D flatter) should be applied.

Once the lens is successfully applied without bubbles, assess the fit at the slit lamp. Several lenses may be successively applied before a satisfactory initial fit is achieved. For patients who consistently flinch, back away, or squeeze their eyelids with attempted application, topical anesthetic can decrease the flinching or squeezing reflex and facilitate application. For patients who have had a negative previous experience with a scleral lens or who are resistant, a different design should be attempted. A custom toric soft lens designed for corneal ectasia or a hybrid lens are appropriate choices.

The technique for assessing the fit of scleral lenses is well-described in the literature. The three zones (central, limbal, and peripheral/scleral) are evaluated and documented. Use the lowest magnification to first assess the central zone and limbal area using the cobalt blue slit lamp filter and a yellow Wratten filter held over the viewing system. Bearing or touch within the central zone or limbus appears as a dark area and should be documented. Next, assess the central vault using a thin optic section positioned over the central cornea, while the illumination arm is placed 45º to 60º from the viewing field. The magnification may need to be increased to allow the clinician to compare the thickness/width of the fluorescein layer with the thickness of the diagnostic contact lens. If the lens thickness is known (typically 350 to 400 microns), the fluorescein layer thickness can be compared to the lens thickness. Note whether the fluorescein layer is thicker, thinner, or about the same as the lens thickness.

Limbal clearance is also evaluated using the optic section with medium or high magnification. The observer should see the thin green fluorescein layer at all four limbal quadrants. If significant limbal touch or compression is present, the lens parameters need modification. The optic zone diameter (OZD) can be increased by 0.4mm, a paracentral reverse curve may be added, and/or the limbal curve can be steepened.

The scleral alignment of the peripheral curves is also judged using a thin optic section. Look for blanching or whitening in one or more zones, impingement, and/or conjunctival entrapment. The peripheral curves can also be modified, and toric haptics are becoming more widely used to minimize conjunctival blanching or impingement, edge lift, midday fogging, conjunctival redness, and other problems.

Once a satisfactory initial fit is achieved and initial settling of the diagnostic lens has occurred, an over-refraction is performed to determine the BCVA with the contact lens. I like to demonstrate the over-refraction with loose trial lenses as the patient looks at the acuity chart as well as while outside of the artificial examination room environment. If the visual acuity significantly improves with the over-refraction, patients are often excited and sometimes emotional at the improved quantity and quality of vision. At this point, there is sufficient information to order initial lenses.

Coding the Visit Appropriate CPT and ICD-10 codes should be used for the services provided, regardless of insurance status. Table 1 lists commonly used CPT codes. The initial visit typically involves an evaluation and management (EM) code because a history and several examination elements (VA testing, slit lamp exam, etc.) were performed. The refraction is coded, if it is performed to document BCVA. Independent testing (such as corneal topography, anterior segment OCT, photography, pachymetry, external photography, etc.) is likewise coded if performed and medically necessary. The appropriate contact lens fitting code is listed along with contact lens material codes. If patients have both medical insurance and vision insurance, the EM codes and independent testing codes can be filed with the medical plan, and the refraction, lens fitting, and lens material codes can be filed with the vision plan.

| EXAM OR CONSULT SERVICES** | INDEPENDENT TESTING, IF NECESSARY | INITIAL CL FITTING SERVICES | CL MATERIALS/DESIGNS | FOLLOW-UP VISITS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99202 Problem focused (PF), new 99212 PF, established 99203 Expanded PF (EPF), new 99213 EPF, established 92002 Intermediate ophthalmological service (inter oph), new 92012 Inter oph, established |

92025 Corneal topography 92285 External ocular photos 92132 Anterior segment OCT 76514 Corneal pachymetry |

92310 Corneal lens, both eyes 92311 Corneal lens, aphakia, one eye 92312 Corneal lens, aphakia, both eyes 92313 Corneoscleral lens 92071 Treatment of ocular surface disease 92072 Keratoconus, initial fitting, both eyes (Medicare), but may be per eye for other insurance plans |

V2510 GP spherical, per lens V2511 GP toric, per lens V2512 GP bifocal, per lens V2513 GP extended wear, per lens V2520 Soft contact lens (SCL), spherical, per lens V2521 SCL toric, per lens V2522 SCL bifocal, per lens V2523 SCL extended wear, per lens V2531 GP scleral, per lens V2699 Other CL |

99212 PF 99213 EPF 92012 Inter oph |

| **These services would be performed after a comprehensive eye examination (92004 or 92014), when the patient presents for evaluation and contact lens fitting and management. Highlighted codes are the most commonly used. | ||||

Patients are responsible for applicable copays for both plans and for paying noncovered and non-approved services. As discussed earlier, it is critical that office staff thoroughly communicate and educate patients about fees, out-of-pocket costs, and insurance eligibility prior to the initial visit using an ABN or other patient information tool. If patients have medical insurance only, they must be informed in advance that they will be responsible for the cost of the MNCLs, the refraction, and possibly the contact lens fitting services, depending on the plan details. Medical plans may require a letter documenting the medical necessity of the contact lenses. Several examples of such letters are provided on the GPLI website (www.gpli.info/coding-billing ).

DISPENSING/TRAINING VISIT

When patients return for the dispensing/training visit, entering VA with habitual correction should be recorded. Perform a brief slit lamp examination to ensure stability since the initial visit and to document the condition of the cornea, conjunctiva, and anterior chamber prior to contact lens application.

Evaluating the VA As with the initial visit, if scleral lenses are being used, the bowl of the lens is filled with nonpreserved sterile saline and mixed with a fluorescein strip prior to application. The new lenses are applied and allowed to briefly settle. Measure VA monocularly and binocularly and, assuming that the VA is close to the expected level, perform a quick over-refraction with loose trial lenses. I typically begin by introducing a +0.50D lens over the eye. If this decreases the VA, then I know that the patient is not overminused. In this case, I’ll next introduce a –0.50D trial lens. If this decreases the VA or if the VA is the same, then I know that the patient is not underminused or overplussed. The over-refraction is therefore plano. If the initial +0.50D trial lens does not change the VA or improves it, then the patient may be over-minused or underplussed. I’ll then compare a +0.50D lens with a +1.00D lens. If the +1.00D lens blurs the VA, the over-refraction is +0.50D. This loose lens process can be continued until blur is obtained with the next +0.50D lens change.

Evaluating Lens Fit/Patient Education Evaluate the lens fit and initial ocular response at the slit lamp. If both are satisfactory, patients are trained in application and removal techniques and should demonstrate this several times to the staff member. The initial care system, solutions, and other supplies (extra cases, application/removal tools, etc.) are provided at this visit. Also provide an instruction sheet summarizing the application/removal techniques, care system, and wearing schedule. Scleral lens instruction sheets are available from B+L Specialty Vision Products (www.bausch.com/ecp/our-products/contact-lens-care/specialty-lens-care-products/scleralfil-preservative-free-saline-solution ) and from the Association of Optometric Contact Lens Educators (AOCLE) (http://aocle.org/healthyHabitsScleral.html ). An instructional video for scleral lenses is available on the Scleral Lens Education Society website at www.sclerallens.org/how-use-scleral-lenses .

A follow-up visit is typically scheduled for one to two weeks. Patients should wear the lenses to the visit, assuming vision and comfort are acceptable. If the lens (or lenses) needs to be reordered, allow adequate time for the new lenses to be received and verified. If the initial fit is adequate, but not optimal, dispense the lenses so that patients can practice application, removal, and lens handling until the new lenses arrive. Wearing time is typically kept to a minimum.

If patients are not able to demonstrate satisfactory application and/or removal, the lens (or lenses) is not dispensed. Some patients become frustrated and fatigued after multiple unsuccessful attempts during this visit and need to be rescheduled for additional training. At home, patients can practice retracting the lids with the fingers of one hand and touching the cornea with a viscous artificial tear drop placed on the finger of the other hand. They should perform this with both eyes open using either a flat or magnifying mirror. This technique can help teach patients to overcome the blink and flinch reflexes and the apprehension associated with lens application.

FOLLOW-UP VISITS

At the follow-up visit, an interval history is recorded documenting the patients’ experience with the lens (or lenses) dispensed at the previous visit. Patients should report improved vision with the lenses and increasing proficiency and confidence with lens application/removal, handling, and care. Record entering VA with whatever vision correction (if any) the patient is using at presentation. Ideally, this would be the lens (or lenses) dispensed at the previous visit, but this is not always the case.

If the VA with the lenses is satisfactory and close to the expected level, a spherical over-refraction can be performed with loose (±0.50D) trial lenses. Always perform a slit lamp examination to assess the lens fit and the ocular response to the lens. This is an important point that is not always fully appreciated by trainees or new practitioners. The primary purpose of the visit is to evaluate the ocular response to the treatment plan with MNCLs. Students and new practitioners may assess the lens fitting characteristics but may not assess the underlying ocular response to the lenses. Evaluate the ocular response to the lens based on the interval history and symptoms, examination level, and medical decision-making. At minimum, examine the conjunctiva, cornea, and anterior chamber for changes or adverse effects, and document these in the record. After a satisfactory fit is achieved (usually within a few visits), follow-up visits are billed with an EM office visit code.

If patients are adapting as expected, schedule another follow-up visit for two to four weeks or whatever interval the practitioner feels is appropriate. If patients have been referred by another practitioner, a report or letter should be sent at the conclusion of the visit.

CONCLUSION

MNCLs are a transformative treatment option for many patients suffering from debilitating diseases of the cornea and ocular surface. MNCLs can restore or improve visual function and enhance the quality of life for our patients in a meaningful way. This article summarizes my procedure for managing patients who have corneal ectasia, scarring, dystrophy, post-surgical conditions, and other pathology using MNCLs.

Because these patients often have complex medical conditions requiring multiple visits over weeks or months, patient education is probably the most important part of the process. The office should have well-designed forms, brochures, and other tools to educate and inform patients prior to the initial visit. I hope this article inspires practitioners to provide this important and appreciated service to their patients. CLS