At the beginning of the 20th century, very few contact lens options were available, and most of the development was taking place in Europe and England. One of the most interesting stories of this era and for the next 60 years is that of Adolf Müeller-Welt. Born in Wiesbaden, Germany in 1904, Adolph was the son of glass artificial eye maker, Adolf Alvin Müeller. In 1920, the Müeller-Welt family moved to Stuttgart, Germany, where they carried on the family business as producers of glass artificial eyes. Although trained to be a part of the prosthetic eye business, Adolph developed an additional interest in contact lenses. At the age of 24, he began to produce what appears to be the first viable “fluidless” glass scleral lens. Unlike other sclerals during this time—and unlike today’s sclerals—instead of filling the bowl of the lens with an application fluid, his design allowed tears to circulate beneath the lens during patients’ wearing time.

Unique Manufacturing

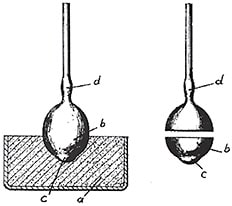

His manufacturing process was unique too, as he produced lenses by blowing glass into a pre-shaped mold of gypsum and marble (Figure 1). However, even though his family had dabbled in contact lenses, they did not think that contact lens manufacturing was a sustainable business. Adolf and his new wife, Ruth Raisig, persisted. Using a small inheritance that Ruth had received, the Adolph Müeller-Welt family began producing glass scleral lenses.

Adolf was able to dramatically improve upon other lens designs of the time through his use of a photographic layout and his knowledge of corneal diameter and sagittal height. In 1929, he began blending the transition curve between the corneal and scleral portions of the lens; in 1931, he created the first scleral lens with an asymmetrical haptic. His research culminated in the granting of a U.S. patent for his fluidless lens in 1932.

Additionally, through a patented annealing process, the internal stress in the glass was lessened. This made the glass more resistant to chemical components in the tear film that commonly eroded the surfaces of traditional glass lenses. The Müeller-Welt glass was so stable that it could be transferred from boiling water to ice water without cracking or breaking. This durability made it easier to grind quality optics into the anterior surface of the lenses and to produce smooth round edges.

Family History

The authors recently had the opportunity to interview Müeller-Welt’s daughter Brigitte, who related some of her childhood memories. “The World War II years were remarkable for our family. My parents traveled throughout Germany and German-occupied Europe fitting thousands of glass scleral lenses to German officers, who in those years were not allowed to wear eyeglasses while in uniform,” she said. “Looking back, it’s impossible to imagine that while my father was spending his total effort perfecting a wearable contact lens, Stuttgart was under aerial bombardment by the British Royal Air Force, at one point for more than 50 consecutive horrible nights.”

There is significantly more to Brigette’s story, which will be covered in this space in a future column.

As for Adolf, he ultimately immigrated to Canada, then to the United States, where he became involved in developing creative corneal lens designs before returning to Germany, where he died in 1972. And, while no longer under family ownership, the Müeller-Welt Contact Lens Company still prospers in Stuttgart, making it the oldest, continuous contact lens-producing company in the world. CLS