For everyone involved in eye care, 2020 was going to be a special year. The numerous “20/20” puns and articles circulating in January were full of hope and future-gazing. No one could have predicted the direction that the year would take and its resulting impact on the world at large and, for this audience specifically, on the delivery of routine contact lens care. As the end of this unprecedented year has finally come to pass, it feels right to pause and reflect on the last 12 months, to examine the journey that the profession has taken, and to summarize the situation. This article reviews what the profession has learned and asks whether enough is known to successfully navigate the months and years ahead. With no small amount of irony and a large nod to those aforementioned puns, does being approximately one year into the pandemic result in having a useful amount of “20/20 hindsight”?

IN THE BEGINNING

First reports of a “viral pneumonia” of “unknown cause” originating in Wuhan, China reached the World Health Organization (WHO) in the very last days of 2019.1 The WHO declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020, naming the condition coronavirus disease, or COVID-19.1 The organization called on all countries to “detect, test, treat, isolate, trace, and mobilize their people in the response.” As the number of cases continued to grow, countries around the world started recommending periods of lockdown at either regional or national levels. Non-essential businesses temporarily closed, people adapted to working from home, school-aged children transitioned to online learning, and recommendations were made for routine eye care to cease. For North America, those recommendations were made in the middle of March.

The changes to everyday lives and business occurred extraordinarily fast. Eyecare professionals were thrown into a new situation of administering only emergency care while trying to navigate the plethora of information that was produced to advise them on how to offer that service as safely as possible. What precautions were necessary when seeing patients? What were the risks of catching COVID-19 from a symptomatic patient, and what proportion of patients were contagious but asymptomatic? Could the virus—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)—be transmitted via the eyes? The WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) produced information to help healthcare professionals navigate some of these questions. Professional organizations followed suit, with U.S.-based examples including the COVID-19 hub from the American Academy of Optometry2 and advice from the American Optometric Association.3

A TSUNAMI OF INFORMATION

This pandemic has been covered on social media and 24-hour news networks like no global situation has been before. Quality, evidence-based information mixed with sensationalist, inaccurate content made it challenging for the public and healthcare professionals to get to the facts. The pace at which information has been produced is unprecedented; a staggering 71,000 peer-reviewed publications related to COVID-19 were available as of early November, an average of slightly greater than 200 published papers every day since January. Specifically related to the eye, there have been more than 70 publications a month produced, with just under three a month on contact lenses and COVID-19 (Table 1). The deluge of new content makes it incredibly difficult to keep abreast of the information, to have time to evaluate which pieces provide robust, credible data, and to comprehend whether—and how—clinical practice should alter as a result.

| SEARCH TERM | TOTAL # | AVG./MONTH | AVG./DAY |

| COVID-19 | 71,213 | 6,474 | 213 |

| COVID-19 + eye | 791 | 72 | 2.4 |

| COVID-19 + contact lens | 29 | 2.6 | 0.09 |

An early example of the spread of misinformation via social media platforms were reports that contact lens wearers should consider switching to glasses, because their spectacles may protect the ocular environment from exposure to the virus and would reduce the likelihood of them touching their face or eyes. These concerns resulted in the publication of an extensive literature review to determine whether these comments were evidence-based.4 The conclusion, based on the available evidence, was that contact lens wear does not increase the risk of COVID-19.4 The review did recognize the continuing importance of compliant wearing practices, including scrupulous handwashing and drying prior to touching lenses or the face, replacing lenses at the correct interval, correct cleaning practices for reusable lenses and cases, and the avoidance of water, unplanned overnight wear, and wearing lenses when unwell. Those conclusions were summarized in patient-facing materials available at COVIDEyeFacts.org and were echoed in an update to patient information available from the CDC.5

COVID-19 AND THE EYE

The very nature of a global pandemic means that scientists and healthcare professionals are dealing with something that has not been encountered before. Because of this, it can be challenging to establish absolute answers to many relevant questions.

The outer lipid envelopes of viruses that are structurally similar to SARS-CoV-2 are susceptible to the surfactants in simple soap, resulting in the early and continuing advice regarding the necessity of regular and thorough handwashing.6 Viruses that are structurally similar to SARS-CoV-2 are vulnerable to a number of disinfectants such as hydrogen peroxide and solutions with at least 70% alcohol content; this information has been applied in the cleaning protocols introduced into clinical practice.7

Spike proteins on the surface of the virus have a high affinity for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). This affinity is believed to be the pathway by which infection can be initiated, enabling entry of the virus into host cells and subsequent viral replication.8 ACE2 receptors are known to be present in the linings of the nose, tongue, and the alveoli of the lungs.9,10 This correlates well with the most common form of transmission; the virus spreads predominantly via person-to-person contact through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.6,11 However, the evidence for abundant expression of ACE2 on the surface of the eye is equivocal, with some reports saying that yes, the ocular surface is susceptible to CoV-2 infection12-15 and others saying that no, infection will not occur.16,17

So, can the eye be a potential route of infection? Understanding of this question continues to evolve, with several reviews,8,18-21 studies,13,22-29 and case reports30-36 addressing the topic. The average frequency across those publications for the detection of the virus on the ocular surface of patients who have COVID-19 is 3%; and, for studies with up to 1,100 subjects, the average frequency of conjunctivitis is 2.5%. One United Kingdom (U.K.)-based observational study reported a much lower frequency of conjunctivitis, in just 0.34% of 13,680 COVID-19 patients.37 Is there the possibility, therefore, of transmission via an ocular route? Systematic reviews have concluded that “…evidence is not only limited, but sorely conflicting”20 and that the eye is “unlikely to be a main transmission route.”18 However, advice that is consistent across the reviews, and that is sensible given the current uncertainty, is the recommendation for front-line workers, including eyecare professionals (ECPs), to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) of various forms, particularly when dealing with patients who are proven to have COVID-19.8,18,19

WHAT DOES CONTACT LENS PRACTICE LOOK LIKE NOW?

The transition back into routine clinical eye care occurred in the United States by state, approximately two-to-three months after the start of lockdown. Guidelines recommended worldwide to the public at large were implemented in practice: physical distancing, wearing a face mask, adequate ventilation, limiting numbers in the building, and regular and conscientious hand hygiene with soap and water.38 The measures necessary to practice as safely as possible in eyecare settings have been highlighted in recent publications.39-43 The global nature of the situation is illustrated by the fact that a number of organizations, including Euromcontact, the British Contact Lens Association, and the Centre for Ocular Research & Education, have produced their guidance in up to 30 languages.

The new clinical-practice normal starts with patients and staff being screened for symptoms or exposure to risk factors, such as recent contact with COVID-19-positive people or recent travel. Both screening and, if the facilities are available, patient history and symptoms can be conducted via telephone or video communication prior to the appointment to reduce contact time on site.44 The period of lockdown forced many ECPs to embrace telehealth for the first time. This is likely to continue, now that the initial steps have been taken to embrace a new way of triaging patients at distance and obtaining history and symptoms prior to the practice visit.

Inside the office, waiting times should be limited, and waiting areas, if used, should have chairs physically spaced apart with no shared magazines or toys available. Clear plastic barriers can be added at points in the office where prolonged closer conversations may occur, such as at reception and dispensing desks. Thorough and regular cleaning of all shared spaces, particularly high-touch surfaces and any shared instrumentation, is required before and after each patient. To limit potential spread in situations during which closer contact is required, such as at the biomicroscope, breath shields are advised along with both patient and ECP wearing masks and limiting talking during the examination (Figure 1).39

In addition to a face mask, ECPs may choose to use more expansive PPE, such as goggles or a face shield. They may wear scrubs or disposable aprons changed between each patient. For the times in a contact lens appointment when the eye or adnexa needs to be touched—when applying a contact lens to a new wearer or everting the upper eyelid, for example—ECPs may wish to wear gloves. However, the advice on their use is equivocal, with no evidence to suggest that using gloves makes it a safer interaction compared to thorough handwashing with soap and water before and after patient contact. It has been pointed out that patients may expect to see their ECP wearing gloves, providing (from the patients’ point of view) what they may feel is a visible reassurance of safety measures being applied.45

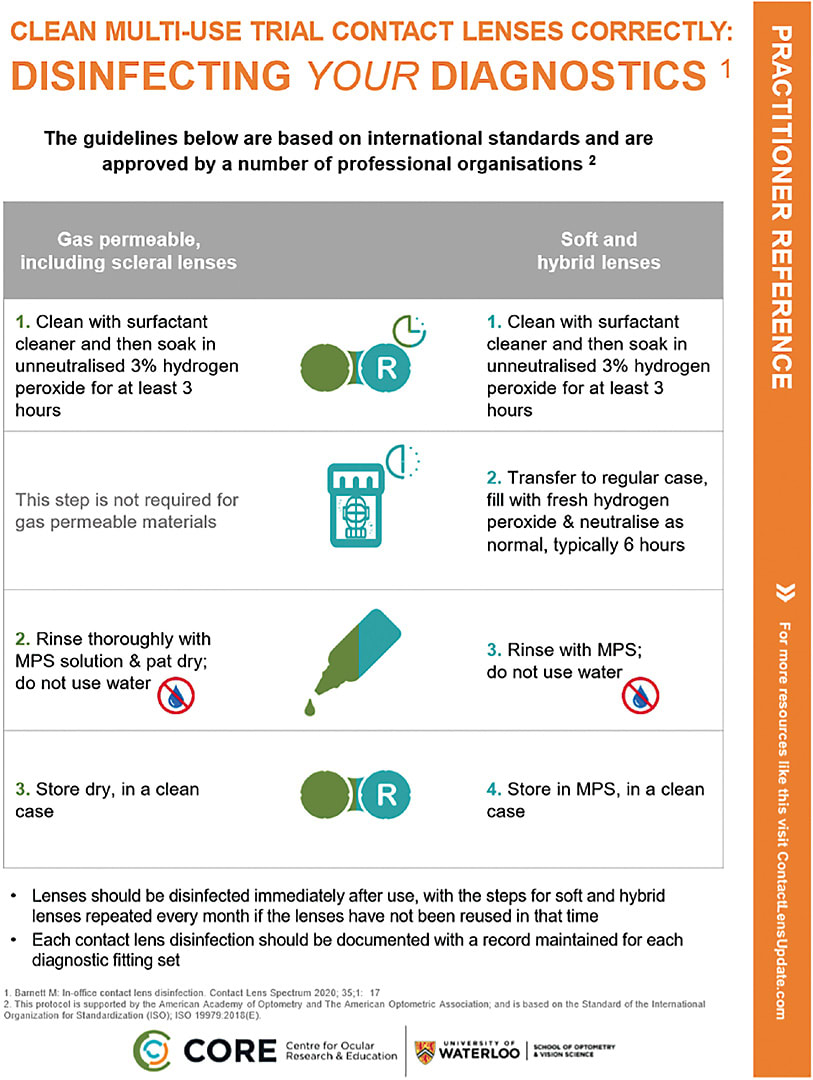

The steps required for the disinfection of reusable diagnostic lenses, while no different than before the pandemic, have been highlighted for ECPs during the year. For all material types, a minimum three-hour soak in un-neutralized hydrogen peroxide is required prior to applying rinsing and storage techniques that differ based on the lens type (Figure 2).

As routine contact lens practice started up during the summer of 2020, it did so with some regions in the world recommending the avoidance of new contact lens fits46 based on concerns that the increased close contact time required for teaching lens handling should be avoided. In the United Kingdom and Ontario (Canada) where this initial stance was taken, following further consideration of the evidence and options to conduct application and removal training in physically distanced manners, these directives were reversed.47 To reduce contact time, patients can be instructed to review videos and information about the wear and care of contact lenses either at home ahead of their appointment or in the office on a tablet, allowing staff members to remain further away until needed. Follow up of new wearers is important to help address issues that could otherwise lead to dropout.48 For most simple contact lens fits, this can be conducted remotely with a phone or video call from the practice.

In practices in which specialty contact lens fitting is offered, there are also options to help reduce the time spent with patients in practice. It is increasingly possible to make use of empirical fitting, with patient details, refraction, and topography sent to the manufacturer. The resulting lens will need to be assessed on eye, of course; but where possible, ECPs can aim to conduct subsequent follow up remotely too.

The sum total of the precautions necessary for routine practice may result in fewer patients being seen per day. For contact lens practice specifically, ECPs may currently feel the need to focus on conducting routine checks on existing wearers to enable their resupply of lenses and on prioritizing those patients for whom lens wear is essential, such as patients who have keratoconus and those who have high prescriptions. With fewer patients able to be seen per day, it is possible that recommendation of contact lenses to spectacle-only wearers is a lower priority right now. While understandable, it is worth recognizing the value that new lens wearers bring to a practice: the increased opportunity for cross-selling of additional products and patients’ positive recommendation of their ECP to friends and family. There is no indication that the current working conditions under which the profession has to operate are going to ease in the near future; this makes it important to find ways to return to previous habits, including the proactive recommendation of contact lenses to neophytes. Additionally, as outlined below, there are some important patient benefits to consider in relation to the potential refitting of existing wearers and fitting others for the first time.

CONTACT LENS WEAR AND THE PATIENT EXPERIENCE DURING THE PANDEMIC

While ECPs were transitioning from offering emergency-only care back to providing routine services, with all of the necessary precautions that this entailed, what were patients doing? A number of surveys sought to understand the impact on existing lens wearers. The combined results of surveys conducted in the United Kingdom, Spain, France, Germany, Italy, Australia, and South Korea tell a story of reduced contact lens use during lockdown. This was reported by 43% to 72% of wearers,49-52 with the primary reason given for the change in wearing frequency as “decreased need” while at home.49-51 An increase in part-time wear occurred, illustrated by a doubling of this habit from 29% to 62% reported by Spanish lens wearers.50 Among survey respondents, a strong desire was expressed to return to normal levels of contact lens wear, with 90% expecting to achieve that within two-to-three months post-lockdown.52

A positive change occurred in some compliance habits. Nearly 80% of contact lens wearers reported using more diligent behaviors, with 63% changing handwashing habits, conducting this task more thoroughly and frequently.51,52 It remains a good time to revisit, remind, and encourage wearers about compliant lens-wearing behaviors. The potential changes in patients’ lifestyles and subsequent wearing habits may provide a good opportunity to discuss the option of daily disposable lenses, with their advantages of a more flexible wearing regimen, no lens care required, and a decreased rate of adverse events compared to reusable modalities.

An increased use of digital devices and subsequent dry eye symptoms were also part of the patient experience throughout the last few months. With a focus on communication and entertainment use,53 in addition to work, education, and video calls, it came as no surprise to hear that 41% of lens wearers experienced increased awareness of dry eyes since the start of the pandemic when completing these tasks.52 When seeing these patients for routine checks, it is important to ask about their current visual habits, which of course may have changed, along with the comfort of their lenses.

Spectacle-only wearers have likely encountered some new ocular issues during the pandemic as well. Anyone who has to wear a face mask in conjunction with spectacles has probably experienced lens fogging. Those who have to wear masks for prolonged periods of time in the day may also find that they experience dry eye symptoms, termed mask-associated dry eye (MADE).54 Both of these are caused by exhaled breath escaping from the top of the mask, either settling as condensation on spectacle lenses or repeatedly passing over the ocular surface, thereby promoting tear film evaporation and dry eye symptoms.

To reduce spectacle fogging, advise patients to wear a well-fitting mask, with their spectacles sitting over the top, and to use anti-fogging wipes or sprays. Ultimately, this will not be enough for some patients, and a move to contact lenses may be beneficial. Early on in the pandemic, reports of front-line workers preferring contact lenses under their PPE emerged, and as mask wearing has increased for all, many other people may also consider the option. A well-fitting mask, taking regular breaks from eye-drying tasks such as prolonged digital device use, and lubricating drops can all help with MADE; this advice is summarized in an infographic for patients in multiple languages at COVIDEyeFacts.org (Figure 3).

LOOKING AHEAD

As the first full year of the pandemic approaches, what is the state of contact lens practice? What has the profession learned from the steep learning curve that it had no choice but to follow throughout the last few months, and does that experience provide useful “20/20 hindsight” from which it can move forward? Reflecting on the end of 2020, this most extraordinary of years, it is apparent that the eyecare profession, like so many allied healthcare professions, has demonstrated the utmost resilience, professionalism, and adaptability. Patient care has rightly been at the center of all of these actions, ensuring that the environment is as safe as possible and that necessary ocular care can continue to be delivered. Contact lens practice has demonstrated great commitment to patient care, from stories of ECPs delivering lenses to patients’ homes during the lockdown through to the provision of ongoing routine care for existing and new wearers.

Looking ahead, it is important to recognize that the current measures required in clinical practice are likely to continue for the foreseeable future, truly becoming a “new normal.” With that in mind, it is crucial to ensure that a full scope of contact lens practice can be offered and that ECPs adapt to routinely offer new contact lens fits if not already doing so. This includes being able to address the needs of patients who require complex fits and who have diseased corneas as well as ensuring that current wearers are offered the most appropriate lenses for their lifestyle.

There is much to be proud of with how the profession has coped to this point. The key now is to maintain that drive and energy to move forward while maneuvering within the current essential health and safety measures by which clinical practice needs to abide. CLS

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization (WHO). Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response. 2020. Available at www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline#! Accessed Nov. 6, 2020.

- American Academy of Optometry. COVID-19 Hub. 2020. Available at www.aaopt.org/my-covid-hub . Accessed Nov. 5, 2020.

- American Optometric Association. COVID-19 latest updates. 2020. Available at www.aoa.org/covid-19/covid-19-latest-updates?sso=y . Accessed Nov. 5, 2020.

- Jones L, Walsh K, Willcox M, Morgan P, Nichols J. The COVID-19 pandemic: Important considerations for contact lens practitioners. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:196-203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Protect Your Eyes. Available at www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/protect-your-eyes.html . Accessed Nov. 8, 2020.

- Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: What we know. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 May;94:44-48.

- Golin AP, Choi D, Ghahary A. Hand sanitizers: A review of ingredients, mechanisms of action, modes of delivery, and efficacy against coronaviruses. Am J Infect Control. 2020 Sep;48:1062-1067.

- Willcox MD, Walsh K, Nichols JJ, Morgan PB, Jones LW. The ocular surface, coronaviruses and COVID-19. Clin Exp Optom. 2020 July;103:418-424.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004 Jun;203:631-637.

- Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020 Feb 24;12:8.

- Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK. The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird’s Eye View. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020 Apr;11:65-71.

- Zhou L, Xu Z, Castiglione GM, Soiberman US, Eberhart CG, Duh EJ. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed on the human ocular surface, suggesting susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ocul Surf. 2020 Oct;18:537-544.

- Zhang X, Chen X, Chen L, et al. The evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection on ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2020 Jul;18:360-362.

- Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020 May;26:681-687.

- Grajewski RS, Rokohl AC, Becker M, et al. A missing link between SARS-CoV-2 and the eye?: ACE2 expression on the ocular surface. J Med Virol. 2020 Jun 4;10.1002/jmv.26136.

- Lange C, Wolf J, Auw-Haedrich C, et al. Expression of the COVID-19 receptor ACE2 in the human conjunctiva. J Med Virol. 2020 Oct;92:2081-2086.

- Xiang M, Zhang W, Wen H, Mo L, Zhao Y, Zhan Y. Comparative transcriptome analysis of human conjunctiva between normal and conjunctivochalasis persons by RNA sequencing. Exp Eye Res. 2019 Jul;184:38-47.

- Cheong KX. Systematic Review of Ocular Involvement of SARS-CoV-2 in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2020 Sep 26:1-10.

- Güemes-Villahoz N, Burgos-Blasco B, Vidal-Villegas B, et al. Novel Insights into the Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Through the Ocular Surface and its Detection in Tears and Conjunctival Secretions: A Review. Adv Ther. 2020 Oct;37:4086-4095.

- Aiello F, Gallo Afflitto G, Mancino R, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (SARS-CoV-2) and colonization of ocular tissues and secretions: a systematic review. Eye (Lond). 2020 Jul;34:1206-1211.

- Lawrenson JG, Buckley RJ. COVID-19 and the eye. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020 Jul;40:383-388.

- Güemes-Villahoz N, Burgos-Blasco B, Arribi-Vilela A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in tears and conjunctival secretions of COVID-19 patients with conjunctivitis. J Infect. 2020 Sep;81:452-482.

- Karimi S, Arabi A, Shahraki T, Safi S. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 in the tears of patients with Coronavirus disease 2019. Eye (Lond). 2020 Jul;34:1220-1223.

- Kumar K, Prakash AA, Gangasagara SB, et al. Presence of viral RNA of SARS-CoV-2 in conjunctival swab specimens of COVID-19 patients. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Jun;68:1015-1017.

- Seah IYJ, Anderson DE, Kang AEZ, et al. Assessing Viral Shedding and Infectivity of Tears in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients. Ophthalmology. 2020 Jul;127:977-979.

- Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, et al. Characteristics of Ocular Findings of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 May 1;138:575-578.

- Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. 2020 Jun;92:589-594.

- Zhou Y, Duan C, Zeng Y, et al. Ocular Findings and Proportion with Conjunctival SARS-COV-2 in COVID-19 Patients. Ophthalmology. 2020 Jul;127:982-983.

- Zhou Y, Zeng Y, Tong Y, Chen C. Ophthalmologic evidence against the interpersonal transmission of 2019 novel coronavirus through conjunctiva. medRxiv. 2020:2020.02.11.20021956.

- Cheema M, Aghazadeh H, Nazarali S, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis as the initial medical presentation of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Can J Ophthalmol. 2020 Aug;55:e125-e129.

- Chen L, Liu M, Zhang Z, et al. Ocular manifestations of a hospitalised patient with confirmed 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020 Jun;104:748-751.

- Colavita F, Lapa D, Carletti F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Isolation From Ocular Secretions of a Patient With COVID-19 in Italy With Prolonged Viral RNA Detection. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Aug 4;173:242-243.

- Daruich A, Martin D, Bremond-Gignac D. Ocular manifestation as first sign of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Interest of telemedicine during the pandemic context. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2020 May;43:389-391.

- Khavandi S, Tabibzadeh E, Naderan M, Shoar S. Corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19) presenting as conjunctivitis: atypically high-risk during a pandemic. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:211-212.

- Ying NY, Idris NS, Muhamad R, Ahmad I. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Presenting as Conjunctivitis. Korean J Fam Med. 2020 Jun 1. [Online ahead of print]

- Scalinci SZ, Trovato Battagliola E. Conjunctivitis can be the only presenting sign and symptom of COVID-19. IDCases. 2020;20:e00774.

- Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020 May 22;369:m1985.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Available at www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . Accessed Oct. 28, 2020.

- Zeri F, Naroo SA. Contact lens practice in the time of COVID-19. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:193-195.

- Jones L, Walsh K. COVID-19 and contact lenses: Practice re-entry considerations. Optician. 2020 Aug 19:22-28.

- Amesty MA, Alió Del Barrio JL, Alió JL. COVID-19 Disease and Ophthalmology: An Update. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020 Sep;9:1-12.

- Lai THT, Tang EWH, Chau SKY, Fung KSC, Li KKW. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: an experience from Hong Kong. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020 May;258:1049-1055.

- Safadi K, Kruger JM, Chowers I, et al. Ophthalmology practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020 Apr 19;5:e000487.

- Nagra M, Vianya-Estopa M, Wolffsohn JS. Could telehealth help eye care practitioners adapt contact lens services during the COVID-19 pandemic? Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:204-207.

- British Contact Lens Association. Use of gloves in contact lens practice COVID-19 Guidance. 2020 Jun 23. Available at www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Public/Consumer/Use-of-gloves-in-Covid-19.aspx . Accessed Nov. 7, 2020.

- College of Optometrists of Ontario. Return to Work: Infection Prevention and Control for Optometric Practice (May 2020). Available at https://opto.ca/sites/default/files/resources/documents/covid-return-to-work-ipac_0.pdf . Accessed Nov 8, 2020.

- The College of Optometrists. COVID-19: Updates, guidance, information and resources. 2020. Available at www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/covid-19-coronavirus-guidance-information.html . Accessed Nov 5, 2020.

- Sulley A, Young G, Hunt C, McCready S, Targett MT, Craven R. Retention Rates in New Contact Lens Wearers. Eye Contact Lens. 2018 Sep;44 Suppl 1:S273-S282.

- Morgan PB. Contact lens wear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:213.

- García-Ayuso D, Escámez-Torrecilla M, Galindo-Romero C, et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on contact lens wear in Spain. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jul 17;S1367-0484(20)30135-1. [Online ahead of print]

- Vianya-Estopa M, Wolffsohn JS, Beukes E, Trott M, Smith L, Allen PM. Soft contact lens wearers’ compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Aug 14;S1367-0484(20)30155-30157. [Online ahead of print]

- Polk M. Seizing the moment. Optician. 2020 Aug:14-17.

- MacKay J. Coronavirus productivity data: How the pandemic is changing the way we use digital devices, apps, and tools. RescueTime:blog. 2020 May 13. Available at https://blog.rescuetime.com/coronavirus-device-usage-statistics . Accessed Sep. 2, 2020.

- Jones L. Why face masks can make eyes feel dry, and what you can do about it. The Conversation. 2020 Aug 19. Available at https://theconversation.com/why-face-masks-can-make-eyes-feel-dry-and-what-you-can-do-about-it-143261 . Accessed Sep. 2, 2020.