When I graduated as an optometrist in the mid-1980s, children born with bilateral congenital cataracts had a very poor visual prognosis. In many cases, treatment was not even recommended due to problems involved with the surgical removal of the cataracts, the poor visual results that were usually obtained after surgery, and the challenges associated with the post-surgical management.1 As contact lenses were rarely used for these patients after surgery, most infants were required to wear very thick and heavy aphakic spectacles that often did not fit easily on their face; they also experienced associated visual problems such as peripheral distortion and restriction of the visual field (due to the so-called “jack in the box” effect).2 In addition, it was not always possible to provide infants with the full aphakic spectacle correction, because the maximum power of spectacle lenses is restricted, even in lenticular form, to generally less than +30.00D.3 The end result was that children born with congenital cataracts—regardless of whether or not they had the cataracts surgically removed—were condemned to a life of low vision.

Happily, the visual prognosis for those who have pediatric cataracts has improved significantly over the last few decades. This is due to a number of factors including earlier detection of congenital cataracts, prompt surgical removal with improved surgical techniques (to limit deprivation amblyopia),2,3 and advances in contact lens technology that have allowed visual rehabilitation with contact lenses immediately after surgery (even at ages as young as 4-to-5 weeks).1,3 With appropriate contact lens management, these patients can now develop relatively normal visual acuities that allow them to easily manage regular activities of daily living both during childhood and into adult life.

Surgical removal of the cataract is the preferred management option for most infantile cataracts.4 This should be performed as soon as possible to reduce the possibility of amblyopia.3 Although, cataract extraction within the first four weeks of life has been shown to greatly increase the risk of aphakic glaucoma.5 Note also that the visual prognosis for bilateral infantile cataracts is much better than for unilateral infantile cataracts. Amblyopia is inevitable with unilateral cataracts, whereas bilateral aphakic infants do not always have significant amblyopia.6

The use of primary intraocular lenses (IOLs) in pediatric cataract surgery is increasing; however, contact lenses are still generally the first option considered for the management of pediatric aphakia.7 Most importantly, contact lenses are easily changed as infantile eyes grow and hyperopia decreases.1,4 Growth in the eye will lead to an increase in the corneal radius of curvature, an increase in corneal diameter, and a reduction in hyperopia. The most rapid growth occurs during the first 18 months of life;8 however, smaller changes in ocular parameters (especially the flattening of the cornea and the reduction in hyperopia) can continue to occur over the following few years.

CONTACT LENS OPTIONS

There are several possible options for contact lens correction of pediatric aphakia. These include soft (hydrogel and silicone hydrogel) contact lenses, silicone elastomer lenses, and rigid contact lenses (corneal, corneo-scleral, mini-scleral, and scleral lenses). For this article, we will adopt a convention proposed by Efron9: “rigid lenses” will refer to all lenses made from rigid GP materials.

Soft Contact Lenses Soft contact lenses are relatively easy to fit to infantile aphakes; historically, this has probably been the primary factor leading to their common use in pediatric contact lens fitting. However, soft contact lenses are more commonly dislodged and ejected from infant eyes as compared to adult eyes due to factors such as excessive eye rubbing.3 Soft contact lenses do not mask corneal astigmatism, and toric soft contact lenses are rarely prescribed to pediatric aphakes due to the excessive lens thickness associated with their prescription. The application and removal of soft contact lenses by parents can also be very difficult due to a combination of the very small palpebral aperture and the high-plus power of the lens.6 Silicone hydrogel contact lenses are definitely the preferred option of soft contact lenses for infantile aphakia, because—even in a high-plus power—these lenses will generally have an oxygen transmissibility that satisfies the Holden-Mertz criterion for no corneal edema during daily wear.10,11

Silicone Elastomer Lenses There is only one silicone elastomer lens on the market, and that lens has a very high oxygen transmissibility due to the silicone elastomer material. Because of their increased modulus, those lenses are easier to apply and will usually result in better visual acuity compared to soft contact lenses.12 They are also more stable on the eye compared to soft or rigid contact lenses and are not as easily rubbed out or mislocated.3

Unfortunately, there are many problems associated with the use of silicone elastomer lenses. First, they are available only in a limited range of parameters.2 Second, they often require more frequent lens replacement, as they are more prone to lens damage as well as to lipid, protein, or mucous deposition due to the hydrophobic nature of the lens material.12-14 Third, the lenses are very expensive, which can be a problem given that they have to be replaced frequently—probably about every three-to-six months—due to a combination of lens degradation and required changes in the lens parameters as the eye grows.13

GP Contact Lenses The use of rigid lenses in pediatric contact lens fitting is becoming more widespread, as these contact lenses can be manufactured from highly oxygen-permeable materials that easily satisfy the Holden-Mertz criterion for both daily and overnight wear, even at the very-high-plus powers required by aphakic infants.10 GP contact lenses can also be manufactured very accurately in virtually any custom parameters. Rigid contact lenses can correct any corneal astigmatism and offer far greater material stability compared to soft contact lenses, as they do not dehydrate on the eye.3 Potential contact lens complications with high-plus lenses—such as corneal vascularization and corneal edema—are less common with GP contact lenses.15

Rigid lens nomenclature is based upon differences in total diameter, although the terminology can vary. For this article, corneal contact lenses are defined as having a diameter of 7.0mm to 12.0mm, whereas corneo-scleral contact lenses have a diameter of 12.1mm to 15.0mm, mini-scleral contact lenses have a diameter of 15.1mm to 18.0mm, and scleral contact lenses have a diameter in excess of 18.0mm.16 The majority of rigid lenses used for pediatric aphakia contact lens fitting are corneal contact lenses. The reason for this is probably two-fold.

First, the smaller diameter of the corneal lenses makes them easier to apply through the much smaller eyelid aperture that is common in babies and infants. Related to this, mini-scleral and scleral lenses are generally fitted in a semi-sealed state with partial tear exchange. Hence, these lenses need to be filled with ophthalmic solution—usually unit-dose or nonpreserved saline—and applied in a manner in which air bubble formation under a lens is prevented; this can be very difficult to achieve with infants, who are often quite uncooperative.

Second, the initial cost of the larger-diameter mini-scleral and scleral contact lenses is considerably higher compared to the cost of corneal contact lenses; unfortunately, this is a significant factor that needs to be taken into consideration given that the lenses will need to be replaced on a frequent basis due to required changes in refraction and fitting associated with the growth of the eye.3

Corneal GP contact lenses do have disadvantages. Initially, they are generally less comfortable compared to soft contact lenses. Due to the greater precision required with GP corneal lens fitting, these lenses will need to be modified more frequently as the eye grows.17 As they do not mold completely to the shape of the cornea, rigid contact lenses are more prone to foreign bodies being trapped beneath them compared to soft contact lenses. Mechanical irritation and subsequent corneal abrasions can be a problem if infants do rub their eyes, and GPs are more easily ejected from the eyes compared to soft lenses.18 It should be noted that mini-scleral and scleral contact lenses offer many advantages over corneal lenses including superior initial comfort, good stability on the eye, excellent vision, and less corneal abrasions (due to the fact that these lenses are fitted with corneal clearance and in a semi-sealed state).19 Hence, these contact lenses should be strongly considered once aphakic children have reached early school age (i.e. > 6 years), as lens replacement will be less frequent at this age due to a significant reduction in the rate of growth of the eye, and application of these lenses will generally be easier due to a child being more cooperative.

CASE REPORT

A 6-year-old boy had been referred to my practice for contact lens management of bilateral aphakia. Ocular history revealed that he had been born with congenital cataracts that were surgically removed at age 10 months. At this time, he was fitted with spherical soft (high-water-content hydrogel) contact lenses that he wore with reasonable success on a daily wear basis over the next five years. He often had sore, red eyes while wearing these lenses, and he frequently lost the soft contact lenses due to rubbing them off of the eye. There were also concerns about the visual acuity obtained with these lenses due to the high degree of corneal (and refractive) astigmatism in both eyes that was not corrected by the spherical soft contact lenses. He presented wearing his aphakic bifocal spectacles, as he had ceased wearing his soft contact lenses a few days earlier.

Visual acuities were OD 6/7.5+, OS 6/7.5+, with a manifest spectacle refraction (at a vertex distance of 12mm) of OD +15.25 –2.75 x 007, OS +15.50 –2.75 x 171. The ocular refraction (to the nearest 0.25D) was calculated to be OD +18.75 –4.00 x 007, OS +19.00 –4.00 x 171. With a +2.50D add, this patient was able to achieve near acuity of N5 with both eyes. Dilated fundus examination was unremarkable, and intraocular pressures were within normal limits. A slit lamp exam revealed some mild bilateral peripheral corneal epithelial hypertrophy and corneal vascularization (about 0.75mm) associated with the previous soft contact lens wear. Assessment of his visual axes showed them to be aligned at both distance and near. Relatively normal binocular function was demonstrated, with stereopsis of 50 seconds, and there was no sign of amblyopia in either eye.

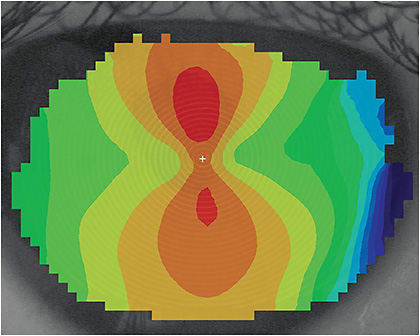

Videokeratoscopy revealed that he had a significant degree of regular with-the-rule astigmatism in both eyes (Figures 1 and 2). The “simulated keratometry” readings obtained through videokeratoscopy were as follows:

OD 43.44 (7.77) @ 008 47.54 (7.10) @ 098

OS 43.05 (7.84) @ 170 46.94 (7.19) @ 080

Due to his previous problems with soft lens wear and the desire to maximize the visual acuity in both eyes, he was refitted with a pair of GP bitoric lenses in the following parameters: OD 7.75mm and 7.10mm base curves (BCs), 7.80mm back optic zone diameter (BOZD), 8.35mm and 7.70mm secondary curve (first peripheral curve [BPR 1]), 8.80mm diameter out to the secondary curves, 9.15mm and 8.50mm tertiary curves (second peripheral curve [BPR 2]) toric radii, 9.80mm total lens diameter (TD); +18.50/+14.50 back vertex powers (BVP), in Boston XO (Bausch + Lomb) with a green tint; and OS 7.80mm and 7.15mm BCs, 7.80mm BOZD, 8.40mm and 7.75mm BPR 1, 8.80mm diameter out to the secondary curves, 9.20mm and 8.55mm BPR 2, 9.80mm TD, +18.75/+14.75 BVP, in Boston XO with a blue tint.

Both contact lenses had a compensated bitoric (spherical power equivalent) design, as diagnostic fitting confirmed there to be negligible residual (non-corneal) astigmatism in both eyes.20 This was expected given that for both eyes, the corneal astigmatism was approximately equal to the refractive astigmatism in the ocular refraction. Calculation of the toric back vertex powers for both contact lenses was performed using basic GP lens optics and tear lens formulas. Readers who need to review the optical considerations of GP toric contact lenses are referred to my book chapter in Contact Lens Practice, 3rd Edition.20

Both contact lenses demonstrated excellent centration and movement on the eye as well as good alignment with the cornea. Vision with the contact lenses was OD and OS 6/9.5, and the sphero-cylindrical over-refraction was plano in both eyes. Multifocal spectacles—incorporating a distance prescription of plano and a +3.00D near add for both eyes—were prescribed for use over the contact lenses. This patient adapted very well to the rigid lenses, and within a few weeks he was wearing them on a full-time daily wear basis without any problems.

He has continued to present to my practice for ongoing contact lens management over the last 12 years, and he has continued to wear his GP bitoric contact lenses without any issues. During this time, his contact lens prescription has been modified a number of times, as with age, there has been a reduction in his hyperopia along with a slight increase in both his corneal curvature and corneal diameter.

SUMMARY

In summary, the fitting of a pediatric patient into contact lenses continues to evolve in a very positive direction. The options—including soft contact lenses and spherical and bitoric GP lenses—have life-changing benefits, and the future holds great promise for even better materials and designs. CLS

REFERENCES

- Moore BD. Optometric management of congenital cataracts. J Am Optom Assoc. 1994 Oct;65:719-724.

- Tromans C, Wilson H. Babies and children. In Efron N. Contact Lens Practice, 3rd Edition, Elsevier, London; 2017:268-274.

- Lindsay RG, Chi JT. Contact lens management of infantile aphakia. Clin Exp Optom. 2010 Jan;93:3-14.

- Lambert SR, Drack AV. Infantile cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996 May;40:427-458.

- Vishwanath M, Cheong-Leen R, Taylor D, Russell-Eggitt, Rahi J. Is early surgery for congenital cataract a risk factor for glaucoma? Br J Ophthalmol. 2004 Jul;88:905-910.

- Moore BD. Paediatric cataracts – diagnosis and treatment. Optom Vis Sci. 1994 Mar;71:168-173.

- Lambert SR, Aakalu VK, Hutchinson AK et al. Intraocular Lens Implantation during Early Childhood: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2019 Oct;126:1454-1461.

- Moore BD. Mensuration data in infant eyes with unilateral congenital cataracts. Am J Optom Physiol Optics. 1987 Feb;64:204-210.

- Efron N. Preface. In Contact Lens Practice. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

- Holden BA, Mertz G. Critical oxygen levels to avoid corneal oedema for daily and extended wear contact lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984 Oct;25:1161-1167.

- Efron N, Morgan PB, Cameron ID, Brennan NA, Goodwin M. Oxygen permeability and water content of silicone hydrogel contact lens materials. Optom Vis Sci. 2007 Apr;84:328-337.

- De Brabander J, Kok JHC, Nuijts RMMA, Wenniger-Prick LJJM. A practical approach to and long-term results of fitting silicone contact lenses in aphakic children after congenital cataract. CLAO J. 2002 Jan;28:31-35.

- Szczotka L. RGPs for the Pediatric Patient. Contact Lens Spectrum. 1998 Aug;13:18.

- Lambert SR, Kraker RT, Pineles SL, et al. Contact Lens Correction of Aphakia in Children: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2018 Sep;125:1452-1458.

- Efron N. Complications. In Contact Lens Practice (3rd Edition). Elsevier, London; 2017:385-409

- Downie LE, Lindsay RG. Contact lens management of keratoconus. Clin Exp Optom. 2015 Jul;98:299-311.

- McQuaid K, Young TL. Rigid gas permeable contact lens changes in the aphakic infant. CLAO J. 1998 Jan;24:36-40.

- Amos CF, Lambert SR, Ward MA. Rigid gas permeable contact lens correction of aphakia following congenital cataract removal during infancy. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1992;29:243-245.

- DeNaeyer GW. Improve Your Scleral Lens Fitting Success. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2014 Nov; 29:22-25.

- Lindsay RG. Toric rigid lens fitting (Chapter 16). In Efron N. Contact Lens Practice, 3rd Edition. Elsevier, London, 2017:156-162.