Arcus Senilis and Dry Eye

History

This patient, a 66-year-old female who is an executive secretary, was referred to our clinic in June 2021. She reported ocular discomfort with symptoms of dry eye, and her visual acuity was also affected over the last 12 months. She was seen by three ophthalmologists prior to her consultation with us, but no effective solution was achieved. She had been prescribed dexamethasone and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride monohydrate, sodium hyaluronate gel, and lutein and zeaxanthin supplements. Symptoms were not resolved. I co-managed this case with an ophthalmologist from my practice; we examined the patient and were intrigued by her symptoms.

Corneal Biomicroscopy

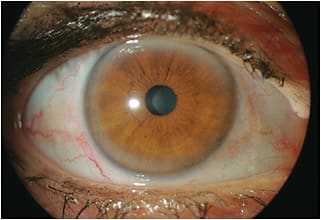

During initial slit lamp examination, we observed a 360º peripheral corneal opacity that immediately led to the probable diagnosis of arcus senilis, the most common peripheral corneal opacity, especially in elderly individuals. It was dense in the superior and inferior cornea and more discrete nasally and temporally. The left eye (Figure 2) had a larger and denser superior band compared to the right eye and coincidentally is where there is manifested astigmatism.

The patient mentioned that she believed that her astigmatism had progressed, and we also observed what could be a pseudopterygium and maybe a slight alteration of the peripheral corneal thickness. This could be a differential diagnosis of early Terrien’s marginal degeneration. We did not find signs of initial vascularization around the limbus, and it was not clear whether there were signs of peripheral thinning.

We instilled fluorescein and lissamine green to investigate the extent of the dry eye condition,1 which was the most perturbing symptom. Neither indicated signs of severe dry eye disease. We observed mild atrophy of the meibomian glands. The tear meniscus was normal, and there were staining dots at the lower cornea, possibly due to incomplete blinking. There was also mild guttata. Tear breakup time (TBUT) was OD 30 seconds and OS 20 seconds. Schirmer’s test resulted in OD 9mm and OS 5mm. We performed the test with anesthesia to provide an accurate measure of the basal tear production.

We performed autokeratometry and autorefraction, which provided the following data:

| Ks | OD 44.50 @ 014 x 45.50 @ 104 (7.59mm x 7.43mm) OS 44.75 @ 148 x 45.75 @ 58 (7.54mm x 7.39mm) |

| Rx | OD +2.25 sph. OS +2.50 C –0.75 @ 155 |

This was important, as we learned that there was no induced astigmatism but rather hyperopia and presbyopia combined. The changes in visual acuity may also be related to the dry eye condition. We conducted specular microscopy, which indicated a normal endothelial count, with a cellular density of 2,724 cells/mm2 OD and 2,785 cells/mm2 OS. (Figure 3).

We decided that the data obtained with the autorefractor was sufficient to evaluate the anterior corneal curvature, so we did not perform corneal topography or tomography.

We examined the peripheral cornea to evaluate whether there was thinning or superficial vascularization; our initial observation was ultimately not relevant but was suspicious when we were still analyzing the case. Figure 4 shows the inferior peripheral cornea during our evaluation.

Discussion

Arcus senilis2 or corneal arcus3 may be associated with familial and non-familial dyslipoproteinemias. Hyperlipoproteinaemia, most notably type II, is frequently associated with binocular arcus, with a less common association in types III, IV, and V. Unilateral arcus is a rare entity that may be associated with carotid disease or ocular hypotony.

The signs of arcus senilis are:

- Lipid stromal deposits starting in the superior and inferior perilimbal cornea, which progress to form a 1mm-wide circumferential band.

- The band is commonly wider vertically than horizontally.

- The central border of the band is diffuse, and the peripheral edge is sharp and separated from the limbus by a clear zone.

- This lucid interval may occasionally undergo mild thinning (senile furrow).

We were suspicious about a differential diagnosis, as the patient’s related symptoms would lead to a more complex case. We initially considered a mild case of Terrien’s marginal corneal degeneration:4

“Terrien’s marginal degeneration usually begins in the superior cornea but may occur anywhere around the limbus. It begins as a fine, punctate, stromal opacity similar to arcus, with a lucid zone. This area becomes superficially vascularized by radial extension of vessels from the limbal arcades. An indentation develops parallel to the limbus, followed by a slow progressive thinning. The thin area has a sloping peripheral edge and a fairly sharp central edge highlighted by a central white line of arcus-like material. During this stage, astigmatism is caused by flattening in the involved area, leading to high degrees of against the rule cylinder that is often irregular.”

We performed optical coherence tomography (OCT) to better evaluate the condition. The OCT scans were taken centrally at 0º and at the perilimbal cornea at 0º, 45º, 90º, and 315º angles. The exam showed a relatively normal thickness in all angles, with a slight alteration at the inferior perilimbal area.

Figure 5 shows some images of the inferior perilimbal cornea where we evaluated for signs of thinning OD. The OCT revealed similar patterns OS (Figure 6).

The images confirmed the first suspicion of arcus senilis, but we still needed to manage the symptoms presented by the patient. The OCT images were important to have a closer look at the peripheral cornea and limbus; they helped to observe this area in detail, especially at the inferior perilimbal cornea, without the reflex of the cross-section beam at the slit lamp. We were more confident to exclude a more complex diagnosis.

The next step was to focus on the patient’s symptoms and complaints. The anamnesis is important when there are no visible causes, especially when the patient reported that the symptoms had started in the last 12 months. At this stage, we must consider the patient history, observe blinking, and ask questions but especially be willing to listen to the patient and try to understand the patient’s daily activities, work environment—even psyche and social history may be of interest.

The patient’s main complaint was dry eye and visual deterioration. She informed us about her daily routine, working in front of a computer screen during working hours and also wearing a face mask for many hours.

We identified that her exhaled breath was being expelled through the top of the face mask, directing the air to her eyes. It is known that long hours in front of a computer screen may reduce the blinking rate. Adding the air from breathing with a face mask results in more severe symptoms of eye dryness. The findings corroborate a recent study on mask-associated dry eye (MADE) along with prolonged screen time.6

MADE may worsen the symptoms in patients who have pre-existing dry eye disease; in this case, a post-menopausal patient who works in front of a computer screen, probably with air-conditioning or a ventilation system. We informed and instructed the patient that wearing the mask appropriately or carefully taping the top edge to the nose may help to minimize the exhaled air forced over the eyes.

The patient also had partial atrophy of the meibomian glands, which further contributed to worsening the symptoms. She mentioned that the symptoms were more intense in the morning when she woke up. We instructed her to ask a family member to observe whether she sleeps with her eyes semi-closed.

We prescribed an ophthalmic lubricant gel before bedtime and higher-viscosity eye drop during working hours, especially when symptoms were significant, and we prescribed a specific product for lid cleansing. We also instructed the patient to apply moist warm compresses with gentle lid massage in an effort to drain the meibomian glands.

Scleral lens fitting would be a clear indication if Terrien’s marginal degeneration had been confirmed; however, with all of the gathered information, we could confirm the arcus senilis and that the symptoms were related to other factors. Still, this patient would benefit from a scleral lens fitting due to the dry eye and also to correct the hyperopia and presbyopia.

The patient returned in one week for a follow-up visit. The proposed treatment was successful, so the patient decided to continue with eyeglasses.

Conclusion

This case supports the importance of both careful eye examination and a detailed anamnesis in identifying all of the factors that contribute to determining the pathology, the cause and possible factors that may lead to a differential diagnosis or that may confirm the probable first suspicion. It is also relevant to use the new technology available today if necessary. Specific exams should be indicated only when they are necessary to help with more data and better comprehension of the situation.

In this case, a combination of factors contributed to the symptoms. Meibomian gland dysfunction, MADE, and induced dryness from prolonged computer use during working hours all contributed to exacerbating the symptoms of eye fatigue, dry eye, and ocular irritation.

The patient was correctly instructed, and the proposed treatment proved to be effective.

References

- Asbell P, Lemp MA. Dry Eye Disease: The Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. Thieme Medical Puiblishers. 2006. p. 33–46, 47-51.

- Kansky JJ. Clinical Ophthalmology – A Systematic Approach, 5th ed. Butterworth Heinemann. 2003. P. 120.

- Kaufman H, Barron B, et al. The Cornea, 2nd edition. Ed. Churchill Livingstone. 1989. p. 449, 450, 450f.

- Kansky JJ. Clinical Ophthalmology – A Systematic Approach, 5th ed. Butterworth Heinemann. 2003. P. 123.

- Grayson M. Diseases Of The Cornea. The C.V. Mosby Company. 1979. p. 178–181, 189–191.

- Pandey SK, Sharma V. Mask-associated dry eye disease and dry eye due to prolonged screen time: Are we heading towards a new dry eye epidemic during the COVID-19 era? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Feb;69:448-449.