A 53-year-old Hispanic female presented for a comprehensive eye exam. She had a history of long-standing opacities in both eyes that have gotten larger over time. Her vision was unaffected, but she was concerned about enlarging opacities in both eyes.

Exam Findings

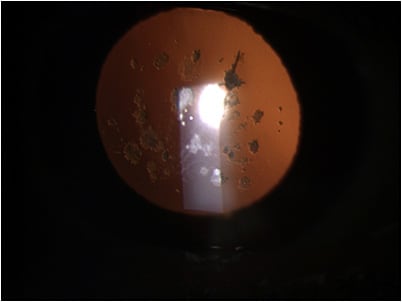

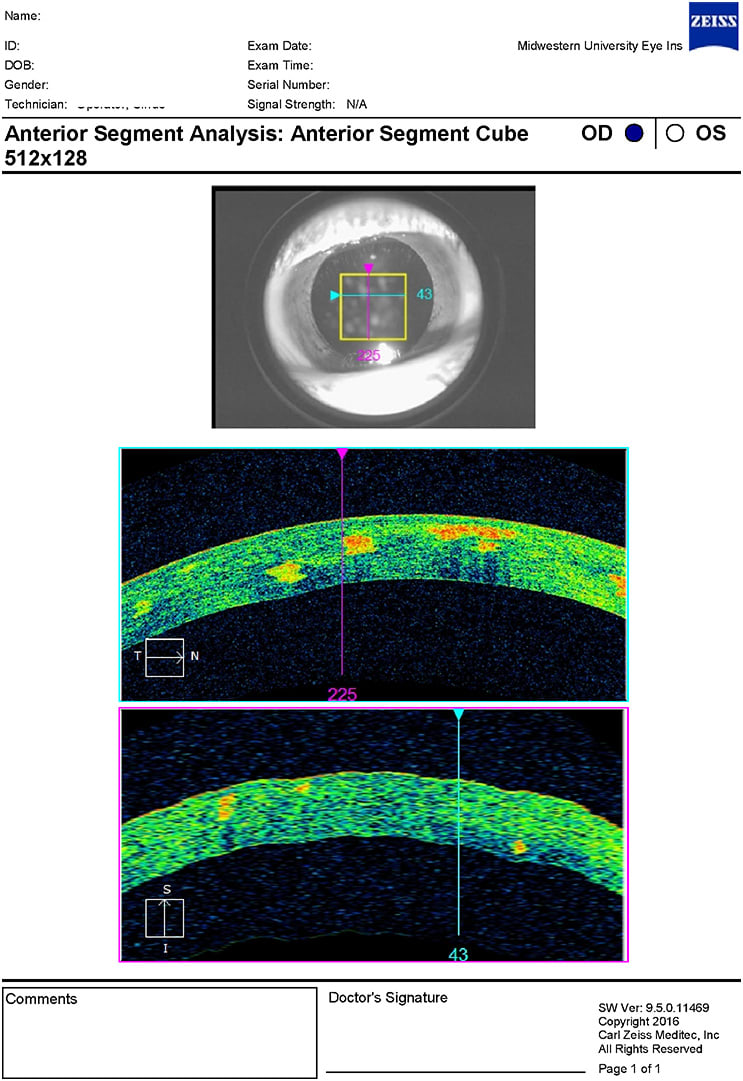

The entrance testing, vision, and slit lamp were all unremarkable. Slit lamp revealed bilateral, symmetrical corneal opacities in the central corneas with a sugar granule appearance and a mild lattice component (Figures 1 and 2). These opacities were easily visible with direct illumination and retroillumination (Figure 3). Video was captured for educational purposes. The opacities were observed to be isolated to the corneal stroma via optic section. An anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) confirmed this in Figures 4 and 5 for OD and OS, respectfully. The OCT showed bilateral hyper-reflective opacities confined to the corneal stroma. Intraocular pressure (IOP) and dilated fundus exam proved to be within normal limits in both eyes. Further discussion with the patient revealed that her mother had a similar ocular appearance, although she was not examined. A diagnosis of Avellino corneal dystrophy was made.

Discussion

Corneal dystrophies refer to a group of inherited corneal disease that are usually bilateral, symmetric, slowly progressive, and not associated with systemic disease or environmental factors.1 The word dystrophy comes from the Greek stems of “dys” meaning “wrong” and “trophe” meaning “nourishment.”2 This was introduced first in 1890 by Arthur Groenouw whom has several corneal dystrophies named after him.3

Classifications of corneal dystrophies are commonly anatomically separated mostly by epithelial, stromal, and endothelial dystrophies. However, variation in presentation and vague nomenclature have led to confusion among conditions and inaccurate publications. For example, publication on central cloudy dystrophy of François suggested that it is an inherited disease, but few publications have proved this.4 Furthermore, the central cloudy dystrophy detailed in that report and posterior crocodile shagreen are clinically indistinguishable and may in fact be the same disease.

Another example is granular dystrophy type 1, which is also referred to as Groenouw type I. Genotyping has now been used to help classify corneal dystrophies, but this has its shortcomings as well. Different gene mutations may lead to the same phenotype (KRT3 and KRT12 both lead to Meeseman’s corneal dystrophy). Additionally, a single gene (TGFBI) mutation may lead to several phenotypic corneal dystrophies (lattice or granular dystrophy). Therefore, a new classification system was warranted.

The International Committee for Classification of Cornea Dystrophies (IC3D) was created in 2005 to establish improved nomenclature that reflected current clinical, pathologic, and genetic knowledge. The initial classification was published in 2008 with a revision in 2015. No further revisions have been made since then.5 The classification groups the conditions by which corneal layer is mainly affected. See Table 1 for the classification:5

|

The IC3D also has a category system to denote the evolution of a corneal dystrophy. It is based on categories 1 to 4 with dystrophies well established in category 1 and new dystrophies in category 4. Dystrophies climb the ladder from category 4 to category 1 as knowledge advances and supporting evidence is shown. Eventually, all valid corneal dystrophies will have category 1 classification, while those in category 4 too long may be removed. The categories are listed in Table 1 with “C#” at the end of each dystrophy that denotes its category.

Category 1: A well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the gene has been mapped and identified and the specific mutations are known.

Category 2: A well-defined corneal dystrophy that has been mapped to one or more specific chromosomal loci, but the gene(s) remains to be identified.

Category 3: A well-defined corneal dystrophy in which the disorder has not yet been mapped to a chromosomal locus.

Category 4: This category is reserved for a suspected, new, or previously documented corneal dystrophy, although the evidence for it, being a distinct entity is not yet convincing.6

In addition to the classification and category, each corneal dystrophy is entered into a template with established headers such as alternative names, genetic locus, inheritance, onset, signs, symptoms, course, etc. for easy comparison between dystrophies. These templates can be found in the 1st and 2nd (updated) edition of IC3D classification of corneal dystrophies.6

Avellino dystrophy (aka granular corneal dystrophy, type 2 and combined granular-lattice dystrophy) is a well-known and researched corneal dystrophy attaining category 1 status. This condition was thought to be a variant of granular corneal dystrophy for nearly 100 years.1,5,6 In the late 1980s, histopathological studies confirmed suspected differences between the two conditions. The term Avellino dystrophy is derived from the Italian district of the same name, where the condition originated. This term was very popular, but now may be considered obsolete due to the worldwide occurrence. Patients will usually present asymptomatically, however, decreased vision may occur as the central cornea is affected.

Avellino dystrophy is a stromal dystrophy that presents initially in young adults with sugar granule-like opacities. These opacities may have a clear center with linear opacities radiating from the small pearls. The linear opacities radiating from the granules may be confused with lattice dystrophy. However, in lattice dystrophy, the lattice lines appear more refractile and will cross one another. In contrast, Avellino dystrophy lines are more opaque and rarely cross.5 This dystrophy occurs in a mutation of the gene transforming growth factor beta-induced (TFBI) and is autosomal dominant. It is estimated that the prevalence for this condition to be 11 per 10,000 persons.7

Treatment is aimed at treating recurrent cornea erosions that may occur and avoiding corneal injury. Refractive surgeries (e.g., laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK), photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), etc.) are contraindicated as they will accelerate the opacification. Phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) may be used to clear coalesced opacities, but the need for retreatment is likely. A penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) may be considered for very advanced cases.

Conclusion

Avellino dystrophy (or more appropriately known as granular type 2) is a fairly rare condition that requires limited treatment. However, families should be counseled about the likelihood of offspring having the condition. Additionally, corneal dystrophy nomenclature has vastly changed in the last 20 years leading to confusion in diagnoses and possible treatment. With time, more consistent terminology will emerge as long as obsolete names are discontinued by clinicians (this author included).

REFERENCES

- Mannis MJ, Holland E. Diseases of the Cornea. In Cornea, Fourth Edition, Elsevier, London, 2022:765-819.

- Warburg M, Møller HU. Dystrophy: a revised definition. J Med Genet. 1989 Dec;26:769-771.

- Groenouw A. Knötchenformig Hornhaüttrubungen [Noduli Corneae]. Arch Augenheilkd. 1890;21:281-289.

- François J. Une Nouvelle dystrophie heredo-familiale de la cornee [A new hereditofamilial dystrophy of the cornea]. J Genet Hum. 1956 Dec;5:189-196.

- Weiss JS, Møller HU, Aldave A, et al. The IC3D classification of the corneal dystrophies-edition 2. Cornea. 2015 Feb;34:117-159.

- Weiss JS, Møller HU, Lisch W, et al. The IC3D classification of the corneal dystrophies. Cornea. 2008 Dec;27:S1-S83

- Lee JH, Cristol SM, Kim WC, Chung ES, Tchah H, Kim MS, Nam CM, Cho HS, Kim EK. Prevalence of granular corneal dystrophy type 2 (Avellino corneal dystrophy) in the Korean population. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010 Jun;17:160-165.