Third in a series of four CE activities for 2023

LEARNING METHOD AND MEDIUM

This educational activity consists of a written article and 20 study questions. The participant should, in order, read the Activity Description listed at the beginning of this activity, read the material, answer all questions in the post test, and then complete the Activity Evaluation/Credit Request form. To receive credit for this activity, please follow the instructions provided below in the section titled To Obtain CE Credit. This educational activity should take a maximum of 2 hours to complete.

CONTENT SOURCE

This continuing education (CE) activity captures key statistics and insights from contributing faculty.

ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION

The goal of this article is to provide practical contact lens solutions to complex eye conditions. Although scleral lens are usually the top choice for these types of patients, other designs in addition to sclerals will be showcased as suitable options.

TARGET AUDIENCE

This educational activity is intended for optometrists, contact lens specialists, and other eyecare professionals.

ACCREDITATION DESIGNATION STATEMENT

COPE accreditation pending.

DISCLOSURES

Roxanna Hemmati, OD, reports no conflicts of interest. Sheila Morrison, OD, has received remuneration and non-COPE CE lecture or authorship honoraria from Euclid, CooperVision, Vistakon, Wave, BostonSight, and Eaglet Ey. Ashley Wallace-Tucker, OD, has received remuneration from CooperVision, Bausch + Lomb, Visioneering Technologies Inc., and Topcon.

DISCLOSURE ATTESTATION

The contributing faculty members have attested to the following:

- That the relationships/affiliations noted will not bias nor otherwise influence their involvement in this activity;

- That practice recommendations given relevant to the companies with whom they have relationships/affiliations will be supported by the best available evidence or, absent evidence, will be consistent with generally accepted medical practice;

- That all reasonable clinical alternatives will be discussed when making practice recommendations.

TO OBTAIN CE CREDIT

To obtain COPE CE credit and instant certificate processing for this activity, read the material in its entirety and consult referenced sources as necessary. Please take the post test and evaluation by following the link below and clicking on the CE Information tab.

Upon passing the test, you will immediately receive a printable PDF version of your course certificate for COPE credit. On the last day of the month, all course results will be forwarded to ARBO with your OE tracker number, and your records will be updated. You must score 70% or higher to receive credit for this activity. Please make sure that you take the online post test and evaluation on a device that has printing capabilities.

NO-FEE CONTINUING EDUCATION

There are no fees for participating in and receiving credit for this CE activity.

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in this educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of Contact Lens Spectrum. This activity is copyrighted to Broadcastmed LLC ©2023. All rights reserved.

This activity is supported by unrestricted educational grants from AccuLens, Contamac, and Metro Optics.

CE Questions? Contact CE@pentavisionmedia.com for help.

RELEASE DATE: AUGUST 1, 2023

EXPIRATION DATE: JULY 14, 2026

SPECIALTY CONTACT LENSES can be life-changing for patients who have complex eye conditions due to disease, genetics, or trauma. Although scleral lenses are a popular option for these patients, corneal GP lenses can be equally effective and potentially less troublesome.

Many patients suffer for years before finding an eyecare provider who has the skill and willingness to tackle their issues. With some added creativity and patience, we can achieve the ideal lens fit that significantly improves these patients’ vision and quality of life. This article will review four cases that may be “worst-case scenarios,” but ultimately resulted in a positive outcome obtained with a specialty contact lens.

CASE #1: CORNEAL LACERATION

It is estimated that nearly 1.5 million people in the U.S. have vision impairment and 1.7 million people have unilateral blindness secondary to eye injuries.1 Contact lenses, especially scleral lenses, can provide greatly improved visual acuity to those patients whose injuries result in corneal scars.

The primary use of scleral lenses in clinical practice is to improve visual function for patients with corneal irregularity. In many cases, the remarkable improvement in visual acuity ultimately prevents or delays the need for a keratoplasty.2

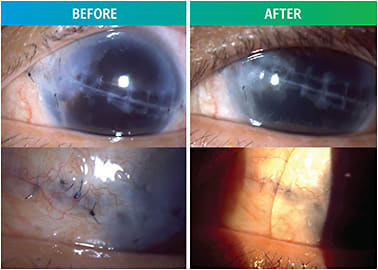

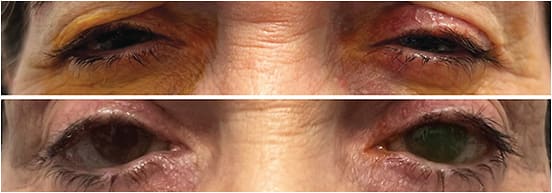

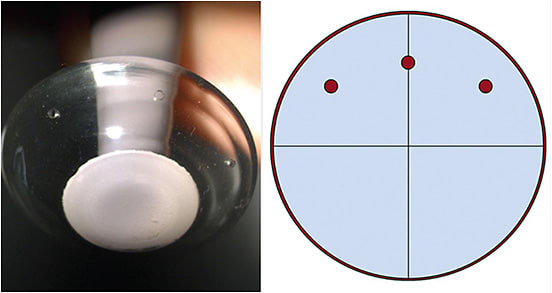

A 58-year-old male presented for a specialty lens consult due to a corneal scar in his left eye. Six months prior, he suffered an open globe injury from a bungee cord that caused a full-thickness corneal laceration from the nasal to temporal conjunctiva. As a result, he was left aphakic and has significant iris atrophy and a dense, diagonal corneal scar through the visual axis that extends onto the sclera. Nylon sutures remained intact after laceration repair (Figure 1).

His corneal specialist referred him for a contact lens fitting in hopes of improving his visual acuity prior to considering a corneal transplant. His entering distance visual acuity (DVA) OS was 20/200, and there was no significant improvement with spectacle correction. With a diagnostic scleral lens and +12.00DS over-refraction (OR) his VA improved to 20/40.

Although this demonstrated that the scleral lens could greatly improve vision, there were a few fitting challenges to consider. First, due to the patient’s extensive scarring and conjunctival sutures, designing a lens that would properly fit and not disrupt his sutures was imperative. Quadrant-specific and scan-based scleral lens designs were both considered, but an impression-based scleral lens was deemed the best option.

Second, due to the patient’s aphakia, he needed a high-powered plus lens with an increased center thickness (CT) that limits the amount of oxygen reaching his already compromised cornea. The patient was informed that if, at any point, hypoxic corneal signs ensued, some of the refractive power from the lens would have to be transferred into overlay glasses to be worn over the scleral lens.

The specific clinical signs of hypoxia that would be monitored were corneal neovascularization, corneal edema, microcysts, and bullae. Although there are varying opinions on how to prevent corneal hypoxia during scleral lens wear, it is recommended to have a post-lens fluid reservoir of no greater than 200μm, a maximum lens CT of 250μm, and a high-Dk material (> 150).3

This patient’s initial scleral lens parameters are shown in Table 1. Vision with this lens was 20/70; a +1.75DS OR improved his DVA to 20/40+2. This lens demonstrated an aligned fit over the cornea, with approximately 200μm of central vault and approximately 50μm of limbal clearance after three hours of lens settling—both of which are ideal. The patient was instructed to wear the lens daily for up to 10 hours a day. No signs of corneal edema were noted after a month of close observation, so a new lens was ordered incorporating the OR with no other fit changes.

| BASE CURVE RADIUS (MM) | POWER (DS) | DIAMETER (mm) | CT (mm) | MATERIAL | DVA | |

| Initial OS | 8.87 | +16.13 | 18.0 | 0.638 | Optimum Infinite (Dk 180) | 20/70 |

| Final OS | 8.87 | +16.88 | 18.0 | 0.633 | Acuity 200 (Dk 200) | 20/60 |

Although there was only a small increase in the lens CT with the increased plus power, small corneal epithelial bullae developed after two months of daily wear. Over several weeks, the bullae were closely monitored and remained stable with no resolution (Figure 2).

Remarkably, after returning to the lens with less power for two weeks, the bullae resolved, which confirmed the need for less center thickness to prevent signs of hypoxia. A third lens was ordered with a slightly reduced power and a thinner center thickness to allow more oxygen to reach the cornea.

The patient’s final lens design parameters are shown in Table 1. His vision with only the scleral lens was 20/60. An OR of +1.50DS was placed in a pair of overlay glasses, achieving 20/30-2 vision. As he was aphakic OD, a +2.50D add was included as well to address his near visual needs.

After several months of observation, the fit remained acceptable, and the cornea did not show any signs of hypoxia (Figure 1). Due to the high-plus power, the recommended CT of 250μm could not be achieved. However, the patient was fit in the highest Dk material available, and the post-lens fluid reservoir remained at about 200μm.

CASE #2: DRY EYE SYNDROME AND DERMATOCHALASIS

Dry eye syndrome (DES) is defined as “a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”4 Epidemiologic studies report the prevalence of DES to be between 7% and 34%, with the highest prevalence in women and people over age 65.4,5 According to the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society (TFOS) Dry Eye Workshop II (DEWS II) Management and Therapy Report, scleral lenses have been identified as step 3 in the staged management of DES after the failure of more traditional routes such as lid hygiene, in-office treatments, and pharmaceuticals.6

A 66-year-old female who has Sjögren’s presented for a scleral consult due to severe dryness, pain, light sensitivity, and reduced vision in both eyes. In addition, her ocular history included primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) OD and OS and wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) OD. Her current ocular therapies included preservative-free artificial tears (PFATs) every one to two hours OD and OS, compounded cyclosporine drops b.i.d. OD and OS, autologous serum tears q.i.d. OD and OS, prednisolone acetate drops q.d. OD and OS, and timolol drops b.i.d. OD and OS.

She also had punctal cauterization OD and OS several years prior, cataract surgery with posterior chamber intraocular lenses (PCIOLs), a tube shunt OS, and was receiving bevacizumab injections for her AMD OD every four to five weeks. Systemic therapy for Sjögren’s included adalimumab and rituximab.

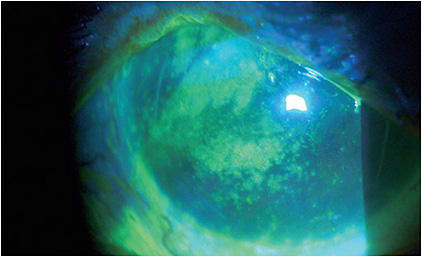

Her entering DVA with habitual spectacles was 20/80-2 OD and 20/40-2 OS. Slit lamp examination (SLE) revealed dermatochalasis in both eyes, rapid tear breakup time (TBUT) in both eyes, minimal tear menisci, dense punctate epithelial erosions (PEEs) and filaments across the corneas, a temporal symblepharon OD, and a tube shunt superior temporal OS (Figure 3).

With diagnostic scleral lenses, the patient’s vision improved to 20/30 OD and 20/25 OS. She also reported an instant improvement in comfort and felt less light sensitive. In addition, her eyes appeared more open and her lids more lifted.

One key consideration for patients who have tube shunts is to provide the least amount of lens interaction to avoid damaging or exposing the tube shunt. In addition, patients who have DES tend to benefit from larger-diameter scleral lenses to provide the most ocular surface coverage and rehabilitation.7 These factors were considered and, ultimately, an impression-based scleral lens was chosen.

Although the initial lenses provided an adequate fit and vision, the patient had challenges with application and removal (A/R). Due to the severity of her dry eye symptoms, she had difficulty fixating on the lens and holding her eyelids open long enough to properly apply and remove them.

Despite attempting to use a scleral lens stand and light device during multiple in-office training sessions, the patient was still unable to apply the lens on her own. Ultimately, her husband assisted her with the A/R process as a temporary measure until her eyes could acclimate to the lenses and her dry eye symptoms improved.

After a few weeks, the patient returned for her follow-up visit frustrated and disappointed, unable to apply the lenses at home and doubting whether this was the proper path for her. After an open discussion about her other option being tarsorrhaphy, another training visit to review the A/R process was recommended. After this visit and diligent practice at home, the patient reported success applying and removing the lenses on her own.

She was instructed to only use preservative-free products to fill her scleral lenses to avoid corneal toxicity. Due the severity of her dry eye symptoms, the patient opted to use a combination of her autologous serum tears and preservative-free saline.

Both lenses had approximately 200μm of central vault and adequate limbal clearance, and were peripherally aligned, including over the tube shunt OS (Figure 4). She was able to wear her lenses successfully throughout the day and described many benefits of full-time wear. Her corneal surface was protected and nourished throughout the day, drastically reducing her dry eye symptoms and use of PFATs. As a bonus, her eyelids appeared more open, which improved the cosmesis of her dermatochalasis (Figure 5).

At the conclusion of the fitting, the patient was extremely grateful and expressed that her scleral lenses were life-changing. She had become much more independent, was able to enjoy the outdoors and was overjoyed that her eyes felt and looked better.

CASE #3: CORNEAL TRANSPLANT AND EDEMA

While scleral lenses are an incredible tool for vision care providers, not all patients are able to wear them full time. Commonly, scleral lenses may be discontinued by fitters due to noncompliance with solutions and difficulty with handling.

A recent study found that 27.4% of new scleral lens wearers stopped wearing their lenses within the first year, primarily a result of lens handling issues.8 Due to their larger size and rigid material, scleral lenses require some technical skill to apply and may be challenging for patients who have limited dexterity or anatomical barriers (e.g., blepharoptosis).9

If one lens modality fails, an alternative specialty contact lens option should be considered. Furthermore, combining any type of contact lens with spectacles can often be an excellent option for patients who have additional visual needs, such as presbyopia or binocular misalignment.

A 74-year-old female who had a penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) OD secondary to complications during cataract surgery presented for a scleral lens fit. Her ocular history also included blepharoptosis OD, pseudophakia with a single vision intraocular lens (IOL) OD, mild epiretinal membrane (ERM) OS, and a moderate cataract OS.

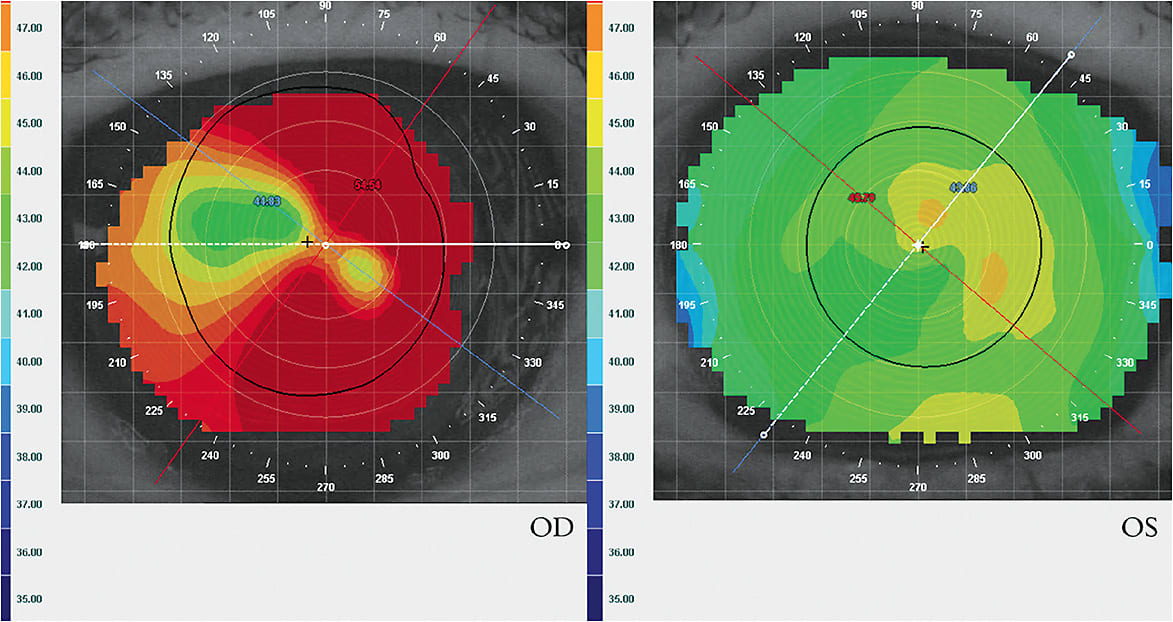

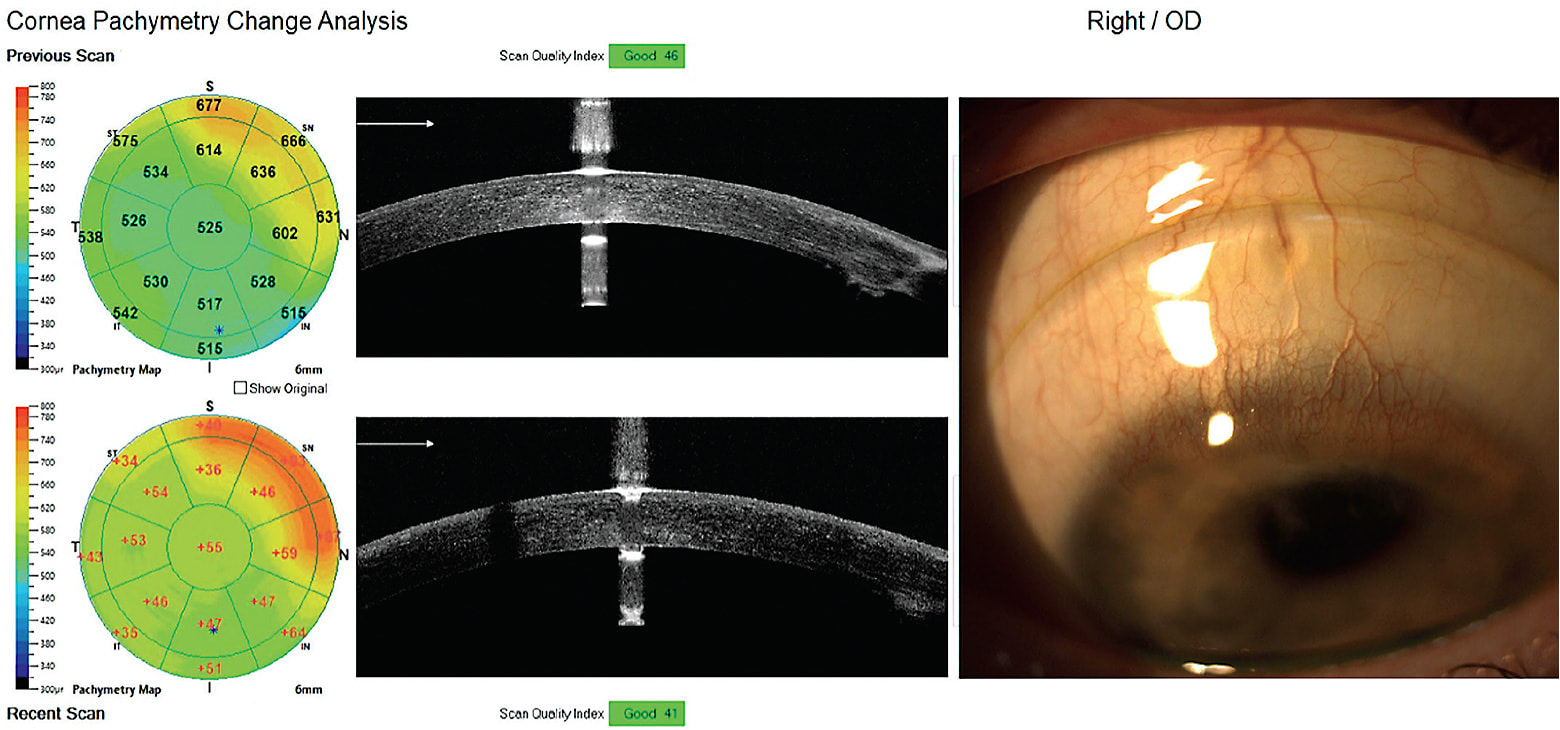

Her entering refraction and VAs were: +3.00 –10.00 x 133 20/100 OD; –3.00DS 20/30 OS. She habitually wore progressive addition lenses (PALs) for the left eye only (balance OD) as her vision OD with spectacles was not usable due to aniseikonia and blur. DVA OD was 20/400 and had been uncorrected for 10 years since her corneal transplant (Figure 6).

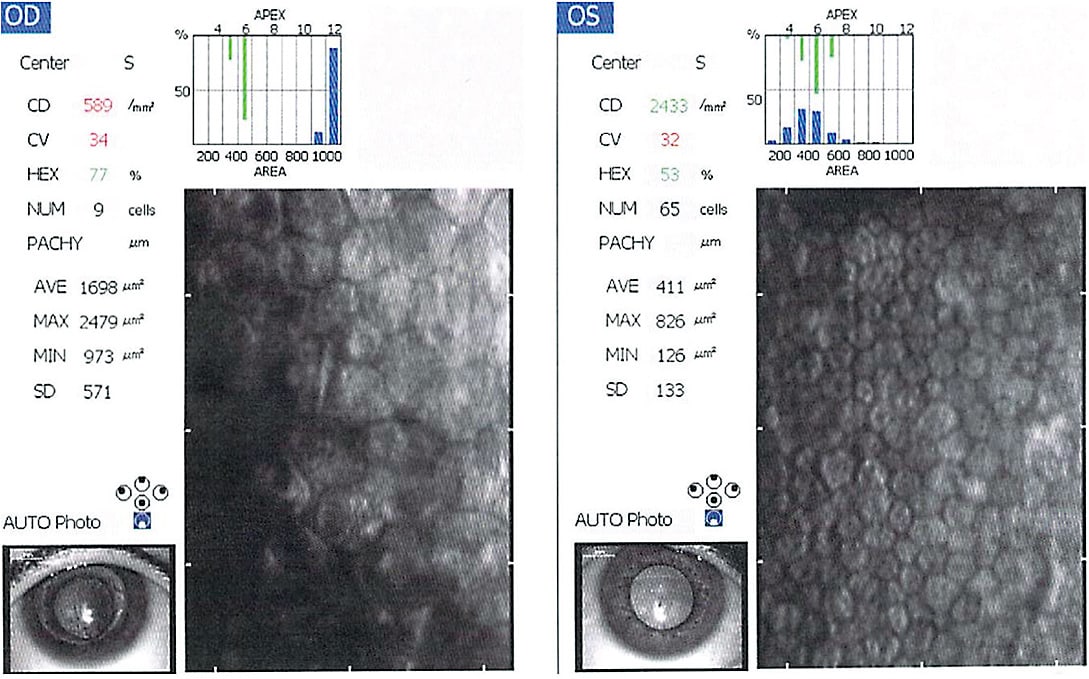

Long-term outcomes for visual rehabilitation after PKP have been studied, and the literature states that scleral lenses should be considered as the lens of choice in eyes with complex corneal geometry; as with visual rehabilitation, their use may delay or prevent further surgical involvement.10 However, patients who have low endothelial cell counts (< 800 cells/mm2) post-PKP who wear scleral lenses are more prone to harmful corneal edema, graft stress, and graft rejections.11 An endothelial cell density (ECD) of 500 cells/mm2 is cited as the threshold to maintain corneal clarity, with more likely decompensation at < 1,000 cells/mm2.12 Cell counts, however, do not necessarily assess function and are difficult to measure accurately and repeatably.13

With a diagnostic scleral lens and sphero-cylindrical OR, this patient’s VA improved to 20/20- OD. A standard scleral lens design was ordered based on diagnostic fitting data.

Despite the scleral lens significantly improving her vision OD, there were also a few early fitting challenges to be considered for this patient.

- New binocular diplopia was immediately apparent with the gain of a usable image in each eye. Due to decompensated exotropia and vertical deviation of eye posture, the patient did not notice a divergent eye posture when the right eye was uncorrected due to habitual blur and visual suppression.

- Mild corneal edema (~30μm thicker on pachymetry and mild microcystic corneal edema on SLE; VA decreased a line) after six-plus hours of scleral lens wear.

- OD blepharoptosis combined with dermatochalasis in both eyes caused the patient to struggle with lens removal due to a ptotic lid that often pushed the superior lens edge down, scraping the cornea. The superior cornea also received less oxygen due to chronic lid obstruction.

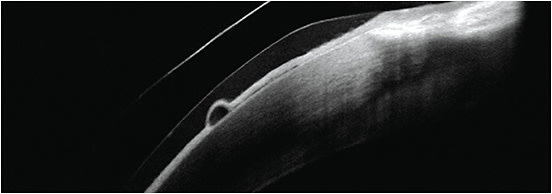

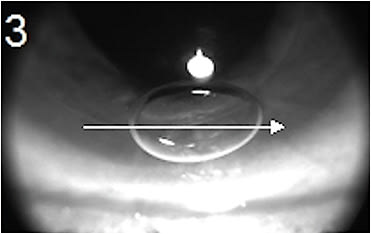

- The patient complained of discomfort that was often due to wearing a lens with unintended air bubbles under the lens that she could not detect (Figure 7). Lens removal was uncomfortable due to a feeling of lens suction despite an adequate initial fitting.

Table 2 shows the initial solutions to address the early fitting challenges.

| Binocular diplopia when wearing OD scleral lens | Prescribed PALs with prism for use over OD scleral lens:OD: Plano, 3pd BI, 2pd BU; OS: –3.00 3pd BI, 2pd BD+2.50 ADD OD and OS Note: This system provided the most optimal vision for safe driving. |

| Corneal edema with six-plus hours OD scleral lens wear | Ordered an endothelial cell count (Figure 8). Consider upgrading to a free-form lens with added safety features and more uniform corneal clearance. |

| Blepharoptosis OD, dermatochalasis OD and OS | Referred for blepharoplasty. |

| Poor application skills and frequent air bubbles under OD scleral lens | Retrained on A/R, introduced a lighted stand for use of both hands holding lids and more ease of application without air bubbles. |

Due to the patient’s low endothelial count, mild corneal edema with lens wear, lens suction, and lens dragging on removal, she was refit with a free-form, fenestrated, higher-Dk scleral lens. Fenestrations in the new lens decreased suction upon removal and gave the patient better control of lens removal (Figure 9).

With added safety features (e.g., fenestrations, higher Dk, improved fit) and reduced wear time (limited to six hours/day for errands and driving), the patient did well with no complications for nearly two years. The follow-up schedule for this patient was every three months due to high risk of graft rejection. She was encouraged not to wear a lens at all when at home and advised to continue all care with her cornea specialist.

Presenting best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) two years after being initially fit with a scleral lens OD: 20/25 (scleral lens); OS: 20/50 (spectacle lens, –4.25DS).

Over about two years, the cataract OS progressed significantly. The patient became uncomfortable during daily home activities and was frustrated by her myopic shift and decreased BCVA OS due to cataract maturation. She was referred to her ophthalmologist for cataract surgery.

Goals for vision were discussed prior to IOL selection. The patient was adamant that she must be able to see for cooking and reading the paper without any correction at home (as a former 3D myope, she could always read without glasses on). When managing complex visual systems that involve corneal irregularity, it is often best to avoid toric or multifocal IOL implants.

The patient already had a single-vision IOL OD from her previous surgery. However, the decision was made to select a multifocal IOL and aim for –1.00DS OS after the lens exchange to best meet her vision goals. Hopefully, she could then perform most daily home activities at intermediate and near without correction.

Cataract surgery OS was successful, and the patient used a single-vision –1.00DS spectacle lens OS for watching TV at home. On days that she did not wear the scleral lens OD (using the left eye to see), she could still suppress the blurry OD vision and eliminate her binocular diplopia. Using monovision optics is another trick to eliminate diplopia when the eyes are not aligned. The patient was able to read and use the computer uncorrected OS. She did, however, prefer her binocular vision, as the vision potential was still higher OD due to the ERM OS.

The patient requested a new contact lens that could be worn longer during the day. She was advised not to wear a scleral lens for extended daily hours due to the risk of complications, but she was successfully refit into a corneal GP lens. It provided slightly worse vision than a scleral lens, but the lens did not cause edema and she could wear it as desired without wear time restrictions.

A scleral lens stabilized this patient’s visual system during the time that she needed to use her right eye as her left eye cataract matured enough to be treated. In the end, her most successful and safest option was a corneal GP lens in the right eye, using spectacles on top with low sphero-cylindrical power, prism, and a PAL OD and OS. The add is asymmetrical with a full +2.50D add OD and a +1.25D add OS. She was happy with her vision for daily activities.

CASE #4: MICROCORNEA WITH PKP AND CHRONIC LENS-INDUCED EDEMA

Ocular albinism is a genetic disorder characterized by vision abnormalities in affected males. Vision deficits are present at birth and do not progress over time. Affected individuals have normal skin and hair pigmentation.14 Anterior segment dysgenesis (ASD) refers to a spectrum of disorders that affect the development of the anterior segment of the eye, which includes the cornea, iris, ciliary body, and lens.15

A 24-year-old male with ocular albinism, anterior dysgenesis, microcornea, refractive laser surgery on both eyes, and a corneal transplant OD presented for a specialty contact lens assessment and fit. His chief complaints were photophobia and light scatter, along with blurry unusable vision OD. He declined a contact lens fitting OS.

His entering refraction and BCVA was –17.00 –5.75 x 132 OD (20/200) and –0.50 –3.75 x 178 OS (20/50). Auto-keratometry was 46.25 @ 173/51.50 OD and 35.00 @ 167/37.75 OS. Horizontal visible iris diameter (HVID) was 10.5mm in both eyes.

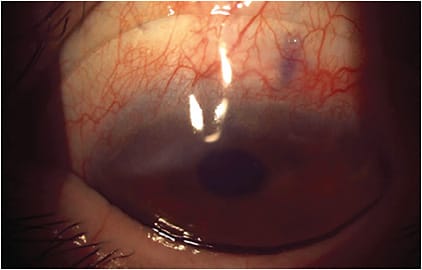

The patient was fit with a free-form impression-based scleral lens with fenestrations and high-Dk material. He developed edema within one to two hours of scleral lens wear and noted halos/rainbows in vision within the first hour of wear (Figure 10). Consequently, scleral lens wear was discontinued.

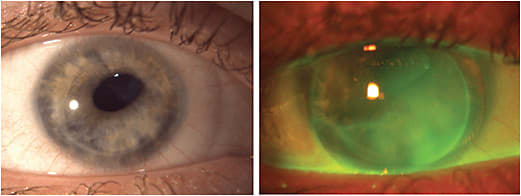

Several attempts to fit a geometrically symmetrical corneal GP lens failed due to the lens becoming dislodged and generally not tolerated due to discomfort. The patient’s cornea was highly sensitive to both light and sensation.

The patient was asked to return to the office for digital scans of the anterior eye using profilometry-based topography. Data collected was used to design a free-form corneal GP lens (Figure 11). The lens did not dislodge, and the vision was 20/50 (meeting BCVA potential), but the patient continued to experience awareness of the lens on-eye. A 13.8mm OAD/7.9mm BCR/–0.25D soft lens was selected and placed beneath the corneal lens as a piggyback (Figure 12).

Generally, when fitting corneal GP lenses on ectatic or postsurgical eyes, it is not necessary or possible to achieve an alignment fit due to corneal shape irregularity. Practitioners should aim to achieve either a three-point touch or apical clearance fitting relationship with no harsh bearing.16

The patient was able to tolerate the lens and did not develop edema using this system. The fitting method was a perfect mix of using current technology to fit a traditional corneal GP modality and modern finesse.

CONCLUSION

These cases prove that patients who have complex eye conditions benefit tremendously from specialty contact lenses of all varieties. Special considerations must be assessed to achieve success, but the final result may not only restore vision but also improve quality of life. CLS

References

- Swain T, McGwin G Jr. The Prevalence of Eye Injury in the United States, Estimates from a Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020 Jun;27:186-193.

- Rosenthal P, Croteau A. Fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral contact lens is an effective option for managing severe ocular surface disease and many corneal disorders that would otherwise require penetrating keratoplasty. Eye Contact Lens. 2005 May;31:130-134.

- Michaud L, van der Worp E, Brazeau D, Warde R, Giasson CJ. Predicting estimates of oxygen transmissibility for scleral lenses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2012 Dec;35:266-271.

- Craig JP, Nelson JD, Azar DT, et al. TFOS DEWS II Report Executive Summary. Ocul Surf. 2017 Oct;15:802-812.

- Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Aug;136:318-326.

- Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II Management and Therapy Report. The Ocular Surface. 2017 Jul;15:575-628.

- Harthan JS, Shorter E. Therapeutic uses of scleral contact lenses for ocular surface disease: patient selection and special considerations. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2018 Jul 11;10:65-74.

- Macedo-de-Araújo RJ, van der Worp E, González-Méijome JM. A one-year prospective study on scleral lens wear success. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43:553-561.

- Bickle KM, Jones-Jordan LA, Kuhn J, et al. Initial scleral contact lens wearing experience. Poster presented at Global Specialty Lens Symposium. Las Vegas. January 2019.

- Severinsky B, Behrman S, Frucht-Pery J, Solomon A. Scleral contact lenses for visual rehabilitation after penetrating keratoplasty: long term outcomes. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014 Jun;37:196-202.

- van der Worp E. A Guide to Scleral Lens Fitting (2 ed.) Monographs, Reports, and Catalogs. 2015 May. Available from commons.pacificu.edu/mono/10 . Accessed June 19, 2023.

- Joyce NC. Proliferative capacity of corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2012 Feb;95:16-23.

- Seitz B, Hager T. Clinical phenotypes of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), disease progression, differential diagnosis, and medical therapy. In Cursiefen C, Jun AS, eds. Current Treatment Options for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy. Springer International Publishing; 2016:25-50.

- Thomas MG, Zippin J, Brooks BP. Oculocutaneous Albinism and Ocular Albinism Overview. 2023 Apr 13. In Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al, eds. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2023.

- Idrees F, Vaideanu D, Fraser SG, Sowden JC, Khaw PT. A review of anterior segment dysgeneses. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006 May-Jun;51:213-231.

- Bennett ES. Keratoconus. In GP Lens Management Guide. Available at gpli.info/gp-management-08 . Accessed April 29, 2023.