FLUORESCEIN IS AN ophthalmic diagnostic that eyecare practices around the world uses multiple times a day. But what do we know about the history of this important diagnostic aid?

Fluorescein was first introduced to the profession in 1888 by Dutch ophthalmologist Manuel Straub (Norn, 1962). The early use of the dye was for visualization of the presence and healing of corneal lesions and ulcers. The dye was initially observed with white light only, and it would be another 50 years before the fluorescent properties (under cobalt blue light) would be recognized (Philips and Speedwell, 2018).

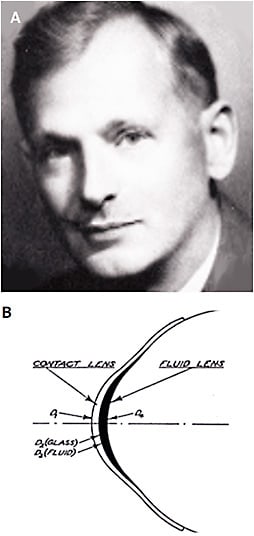

The story leaps ahead to New York City-based optician Theodore Obrig (Figure 1A), who became interested in contact lenses in the early 1930s when he was working at Gall & Lemke Optical Company. At that particular time, he was fitting ground glass scleral lenses from Zeiss in Germany.

Obrig was using Joseph Dallos’s techniques for taking impressions of the eye, which he forwarded to Zeiss in Jena. The lenses were then made by blowing chemically resistant glass against the mold with the optical portion being ground onto the anterior surface of the lens. Delivery time to the U.S. was approximately four months (Bowden, 2009).

It is interesting to note that a pair of Zeiss lenses sent to Leo Waldert, an optician in Rochester, NY, were on the German zeppelin Hindenburg when it crashed and exploded at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey on May 6, 1937 (Bowden, 2009). Obrig found, by chance, that the use of fluorescein and a cobalt blue filter could aid in the fitting of glass scleral lenses. In his 1942 book Contact Lenses, he described how, “on a day when very low lighting was present in the exam room, I noticed a bright green reflex when I used the slit lamp with the cobalt filter in place and fluorescein in the eye.” He realized that the pattern looked green where there was clearance and black where there was touch (Obrig, 1942).

In an article titled “A Cobalt Blue Filter for Observation of the Fit of Contact Lenses,” Obrig proposed the use of fluorescein (placed into the bowl of the lens) and cobalt blue light to view corneal and limbal clearance (Obrig, 1938). He went on to write, “Lens pressure at the limbus or inside the limbus, on the cornea itself is without doubt the reason for discomfort from contact lenses in at least 90% of the patients who complain of the inability to wear their contact lenses” (Heitz, 2014).

In an illustration by Paul Boeder (an engineer with American Optical), it is clear that the early designers of glass scleral lenses fully understood the fundamental principles of scleral lenses that we continue to embrace today—the need for central lens clearance, peripheral corneal clearance, limbal clearance, and scleral landing (Figure 1B). CLS

References

- Norn MS. Vital staining of cornea and conjunctiva. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1962;40:389-401.

- Phillips AJ, Speedwell L. Contact Lenses. Elsevier. 2019;6:4.

- Bowden TJ. Contact Lenses: The Story: A History of the Development of Contact Lenses. Bower House Publications. 2009:132-133.

- Obrig T. Contact Lenses. The Chilton Company. 1942:148.

- Obrig T. A Cobalt Blue Filter for Observation of the Fit of Contact Lenses. Arch Ophthalmol. 1938;20:657-658.

- Heitz, Robert W. The History of Contact Lenses. Wayanborch Publishing. 2014;3:86.