WE RECENTLY INVITED pediatricians and optometrists to complete a brief online survey about market trends in myopia and its management. Here, we provide the results along with some commentary.

PEDIATRICIAN RESPONSES

Pediatricians were asked six questions, mostly yes or no, about visual assessment in their practice, with an emphasis on myopia.

Are you routinely conducting vision screenings in your pediatric patients aged 5 to 12 years? Among respondents, 93% are routinely conducting vision screenings in this age range. Children at the lower end of the age range are susceptible to newly acquired amblyopia (lazy eye) and strabismus (squint), as the sensitive period of visual development extends to age 7 and amblyopia is more easily managed before this age. Beyond the age of 7 years, children are at increasing risk of developing myopia.1

Does your vision screening include an assessment of visual acuity that allows you to screen for myopia (nearsightedness)? Among respondents, 77% include an assessment of visual acuity. This suggests that 23% of pediatricians are not measuring vision in this age group. This is, perhaps, surprising, given that this task is easily delegated.

Does your vision screening include any assessment of refractive error otherwise (e.g., astigmatism, hyperopia, myopia)? Responses to this question were almost evenly split, with 51% answering “Yes.” Pediatricians might use the old-school approach of retinoscopy. Others may have access to a photoscreener or autorefractor. The number of positive responses were unexpected, but may reflect the fact that respondents are interested in vision.

If you screen for myopia and suspect it, do you refer to an eyecare provider? Among respondents, 99% refer to an eyecare provider, with 53% referring to the family’s own eyecare practitioner—either an optometrist or an ophthalmologist. Around one-third are referring to an independent ophthalmologist, with the remaining 12% referring to an independent optometrist.

Some of these answers may be influenced by the availability of practitioners in the area and preexisting professional relationships within the community. While optometrists deliver the majority of primary eyecare in the U.S., pediatricians responding have a preference for those with whom they have some shared training.

Are you aware of the increases in frequency and severity of myopia in children in general? Nearly four-fifths of respondents (79%) are aware of the increases in frequency and severity of myopia in children, likely attributable to both the professional and lay press. Data from the 1999-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)—a nationally representative sample—have been compared with the 1971-1972 NHANES data. Over 30 years, the prevalence of myopia has increased from 26% to 35% in white children aged 12 to 17 years and from 12% to 31% in African American children.2

Are you aware of ophthalmic myopia management protocols that can slow the progression of myopia in pediatric patients? Despite the majority of respondents being aware of the increasing prevalence of myopia among children, only 41% were aware of protocols that can slow the progression of myopia in children.

Myopia control is an emerging but rapidly evolving field with only one drug and one device approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for slowing the progression of myopia.3 Many more options are on the horizon, with some already widely used on an off-label basis.4 These options are discussed below in the context of one of the questions posed to the optometrists.

OPTOMETRIST RESPONSES

Optometrists were asked seven more in-depth questions about management of myopia in their practices.

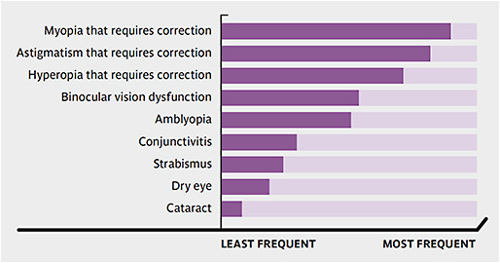

Which ophthalmic conditions do you most frequently diagnose in your young patients (ages 5 to 16 years) in optometric practice? Optometrists were asked to rank these nine conditions from most to least frequent (Figure 1). In Figure 1, a longer bar indicates a higher ranking and a more frequently diagnosed condition. As might be expected in this age range, myopia is the most frequently diagnosed condition, followed by astigmatism and hyperopia. Not only is myopia more common than hyperopia in children and adolescents, it also emerges in this age range1 and parents who bring their children in for an examination may already be aware of the diagnosis.

The next most frequently diagnosed conditions are binocular vision problems that include accommodation and convergence insufficiency and amblyopia, which ideally should have been diagnosed at a younger age. Strabismus is a related, but less common, diagnosis. Dry eye and conjunctivitis are less common but play an important role. Indeed, increased screen use has increased the frequency of dry eye disease among children.5 Finally, cataract is rare in this age group.

Do you believe that myopia is increasing in frequency in your young patients (ages 5 to 16 years)? Only 1 in 7 respondents (14%) stated that they have not noticed an increase in frequency, while half have noticed a small increase in frequency (47%). The remaining two-fifths have noticed a large increase in frequency (39%).

These responses may be influenced by the aforementioned increase in myopia prevalence that has been widely discussed in the professional press. Likewise, it can be hazardous to judge prevalence based on practice traffic. An increase in myopic children in a practice may be the result of a number of factors, such as successful marketing or a pediatrician opening a practice in the same building. Nonetheless, the prevailing impressions of the surveyed optometrists support an underlying increase in the prevalence of myopia.2

Are you actively practicing myopia control in your clinical practice in your young patients (ages 5 to 16 years)? Only 9% of respondents stated that they were not practicing myopia control. One-third of respondents are “just getting started” (32%), with similar numbers replying “moderately” (25%) or “frequently” (33%). Of course, this may reflect some bias in the sample, as those not engaged in myopia control may have been less likely to complete the survey.

Myopia control will likely be an increasing part of optometry practice as more therapies are developed, evaluated, and ultimately approved by the FDA. Any pediatrician will likely be able to locate someone in their area who is already active.

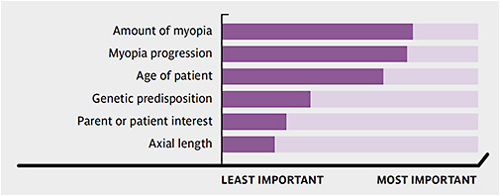

What factors contribute most significantly to your starting of a myopia control regimen for your young patients? Optometrists were asked to rank the six factors that contributed to their starting myopia control by importance (Figure 2). In this figure, a longer bar indicates a higher ranking and a more important factor. The responses identify a group of three important factors and three that are regarded as less critical.

Among the three important factors, the amount of myopia and the rate at which it is progressing are considered the most important. Collectively, these indicate the severity of the condition. Likewise, the age of the patient is regarded as influential, because once present, nearly all myopia will progress, and myopia of earlier onset carries a greater risk of leading to higher levels of myopia by adulthood.6 Thus, 3D of myopia in a 9-year-old is of greater concern than 1D of myopia in a 14-year-old.

Parental or patient interest, parental history of myopia, and axial length are regarded as less important factors by respondents. Motivation of both parent and patient will be the key to compliance, particularly if daily atropine or contact lenses are to be prescribed. Parental history of myopia plays an important role in a child’s risk of developing myopia,7 but once myopia is present, parental history plays a modest role in the rate of progression.

Myopia incidence and progression are nearly always the result of an increase in the length of the eye (axial length), and the rate of myopia progression is highly correlated with the rate of elongation. Nonetheless, this correlation, and the fact that relatively few optometrists have instruments to measure axial length (while it is first on the shopping list for a cataract surgeon), probably resulted in its low ranking.

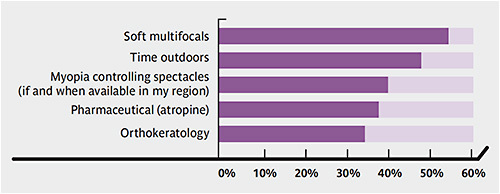

Which of the following treatment options are you most likely to use when first starting a myopia management regimen for your young patients (ages 5 to 12 years)? Optometrists were asked to state which of the five treatment options they were most likely to use when first starting a myopia management regimen in a young patient (Figure 3). The five categories were relatively evenly represented, ranging from 37% for orthokeratology to 53% for soft multifocal contact lenses.

Time outdoors is the most cost-effective option and carries additional health benefits for the child. Increased time outdoors has been consistently associated with a lower incidence of myopia.8 In contrast, the evidence for outdoor time slowing myopia progression is much less,9 although the seasonal variations in progression offer some indirect evidence.10

It is perhaps not surprising that soft multifocal lenses came out on top, as this is the only category with a product that is approved by the FDA for slowing myopia progression.3 Another option is orthokeratology, which uses GP contact lenses fitted flatter than the corneal radius and are worn on an overnight basis. The lens reshapes the cornea, thereby temporarily eliminating the myopia and providing day-long clear vision without the need for correction. They are approved by the FDA for this indication. Orthokeratology has also been shown to significantly slow myopia progression but is not approved by the FDA for this indication (although it is approved for myopia management).11

Low-concentration atropine eye drops can be prescribed for nightly use. The FDA-approved 1% atropine is a powerful cycloplegic and mydriatic, and it is indicated for diagnostic use and in the treatment of amblyopia as an alternative to patching; the child’s good eye receives atropine, forcing them to use the amblyopic eye. This high concentration has long been prescribed by a few clinicians to slow myopia and is used in some East Asian countries.

Concentrations of 0.05% and below are well tolerated by children and also slow myopia progression.12 Low-concentration formulations of atropine are not approved by the FDA and must be prepared by a compounding pharmacy. Thus, both the prescribing and preparing of the drug is outside the purview of the FDA. Of course, the child still has to wear a correction, be it spectacles or contact lenses, so many optometrists will begin with an optical myopia control modality and add atropine if the child is still progressing rapidly, at risk of becoming highly myopic, or both.

Finally, the goal of controlling myopia with spectacles has a long history. Bifocals and the more cosmetically appealing progressive addition lenses (line-free multifocals) generally have been shown to be ineffective. Recently, sophisticated lenses have been developed and shown to be as effective as any other options. These lenses have clear central zones but, in the periphery, there are either 1mm lenslets13,14 or diffusing elements15 that slow myopia progression. While these lenses are available in many countries, they are still being evaluated in the U.S. as part of the path to FDA approval.

Do you believe that a myopia management regimen is standard of care for myopic children and teens in optometric practice today? Optometrists were asked whether they regarded myopia management as the standard of care for myopic children. While 1 in 8 responded “no” (12%), the remainder were evenly split between “yes” (42%) and “getting there, but not quite” (46%).

While those responding to the survey may be more enthusiastic about managing myopia, broader opinion is likely moving myopia control closer to being the standard of care. Of course, practitioner opinion, professional organizations, and insurance companies all play a role in shaping practice.

Which of the following areas of your optometric practice have been improved by the inclusion of myopia management regimens in your care of patients? Finally, optometrists were asked which of four areas of their practices have been improved by the inclusion of myopia management. Improved parent satisfaction was reported by 75% of respondents, while 62% stated that their professional development had been influenced. Almost half reported improved patient satisfaction (49%) and practice revenue (45%), while 9% felt that adding myopia management had not influenced their practice.

THE WRAP-UP

The responses to both surveys have provided some insights into the perspectives of pediatricians and optometrists. There is an interesting and expected difference in the awareness of myopia management protocols that can slow the progression of myopia in pediatric patients.

It is worth noting that the American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) created the Task Force on Myopia in 2019 in recognition of the global increases in myopia prevalence and its associated complications, with representation from the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Optometry, and the American Academy of Pediatrics. The published report16 states that “myopia is a high-priority cause of visual impairment, warranting a timely evaluation and synthesis of the scientific literature and formulation of an action plan to address the issue from different perspectives.” The proposed plan includes education of physicians and other health care providers.

Hopefully, this article represents a few steps on that journey. Look for more information for eyecare practitioners and pediatricians across our platforms in the months to come. CLS

REFERENCES

- Kleinstein RN, Sinnott LT, Jones-Jordan LA, Sims J, Zadnik K; Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error Study Group. New cases of myopia in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012 Oct;130:1274-1279.

- Vitale S, Sperduto RD, Ferris FL 3rd. Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971-1972 and 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009 Dec;127:1632-1639.

- Chamberlain P, Peixoto-de-Matos SC, Logan NS, Ngo C, Jones D, Young G. A 3-year Randomized Clinical Trial of MiSight Lenses for Myopia Control. Optom Vis Sci. 2019 Aug;96:556-567.

- Bullimore MA, Richdale K. Myopia Control 2020: Where are we and where are we heading? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2020 May;40:254-270.

- Gupta PK, Stevens MN, Kashyap N, Priestley Y. Prevalence of Meibomian Gland Atrophy in a Pediatric Population. Cornea. 2018 apr;37:426-430.

- Hu Y, Ding X, Guo X, Chen Y, Zhang J, He M. Association of Age at Myopia Onset with Risk of High Myopia in Adulthood in a 12-Year Follow-up of a Chinese Cohort. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Nov 1;138:1129-1134.

- Zadnik K, Sinnott LT, Cotter SA, et al; Collaborative Longitudnal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error (CLEERE) Study Group. Prediction of Juvenile-Onset Myopia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015 Jun;133:683-689.

- Jones LA, Sinnott LT, Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. Parental history of myopia, sports and outdoor activities, and future myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007 Aug;48:3524-3532.

- Deng L, Pang Y. Effect of Outdoor Activities in Myopia Control: Meta-analysis of Clinical Studies. Optom Vis Sci. 2019 Apr;96:276-282.

- Gwiazda J, Deng L, Manny R, Norton TT; COMET Study Group. Seasonal variations in the progression of myopia in children enrolled in the correction of myopia evaluation trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014 Feb 4;55:752-758.

- Bullimore MA, Johnson LA. Overnight orthokeratology. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Aug;43:322-332.

- Yam JC, Jiang Y, Tang SM, et al. Low-Concentration Atropine for Myopia Progression (LAMP) Study: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of 0.05%, 0.025%, and 0.01% Atropine Eye Drops in Myopia Control. Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan;126:113-124.

- Lam CSY, Tang WC, Tse DY, et al. Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments (DIMS) spectacle lenses slow myopia progression: a 2-year randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar;104:363-368.

- Bao J, Huang Y, Li X, et al. Spectacle Lenses with Aspherical Lenslets for Myopia Control vs Single-Vision Spectacle Lenses: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022 May 1;140:472-478.

- Rappon J, Chung C, Young G, et al. Control of myopia using diffusion optics spectacle lenses: 12-month results of a randomised controlled, efficacy and safety study (CYPRESS). Br J Ophthalmol. 2022 Sep 1;bjophthalmol-2021-321005. [Online ahead of print]

- Modjtahedi BS, Abbott RL, Fong DS, et al. Reducing the Global Burden of Myopia by Delaying the Onset of Myopia and Reducing Myopic Progression in Children: The Academy’s Task Force on Myopia. Ophthalmology. 2021 Jun;128:816-826.