OF ALL THE contact lens neophytes that you fit with lenses today, fewer than three-quarters are expected to still be wearing lenses one year from now.1 The majority of these discontinuations occur in the first (~25%) or second (~47%) months of lens wear.2 If we consider how many patients this equates to over a couple of years, or worse still, the cumulative over any individual’s career, the number can easily exceed several thousand. Yet, it is worth remembering that an estimated 140 million people do manage to successfully wear contact lenses.3

While patient discomfort and unsatisfactory vision are the most commonly reported reasons for terminating wear, lens handling, which is a modifiable factor, can also underlie a patient’s decision to abandon lens wear.1,4 Therefore, it appears that some of the reasons for dropping out of contact lens wear could be overcome with good education and an appropriate management strategy.

Despite such findings, lens handling has remained an under-researched area of optometry, and there is little data to support current training processes. The absence of a strong evidence base inevitably means an increased reliance on anecdotal evidence or clinical pearls passed through professional networks.

For example, the evidence underlying the need for patients to apply and remove lenses a minimum of three times before they’re deemed competent is unclear. Why not four times? Or five? Why apply the scissors method of rigid corneal lens removal over lid manipulation, or vice versa? And at what point should a lens removal device be recommended?4

While we may hold insufficient data to demonstrate the superiority of one lens handling approach over another, our dropout rates are indicative of a system that may benefit from improvement.

The implications of poor lens application and removal techniques are not limited to the financial (e.g., possible reputational damage, lost chair time, and loss of long-term revenue), but also affect patient care and freedom. Macedo-de-Araújo and colleagues reported that the main reason for scleral lens dropouts was poor lens handling (~35%).5 No doubt eyecare practitioners (ECPs) involved with therapeutic contact lens fittings are acutely aware of the impact an inability to acclimate to lens wear can have on a patient’s quality of life.

Following are some of the issues linked to inappropriate lens handling (Figure 1), and the data available for each are considered.

POTENTIAL CONSEQUENCES OF POOR LENS HANDLING

Ptosis and Other Risks of Lens Application and Removal Ptosis may be correlative with both rigid and, less frequently, soft lens wear.6-12 Verhoekx and coworkers calculated the odds ratio for developing ptosis to be 11.7 (6.4 to 21.4; CI = 95) for soft contact lens wearers and 33.6 (18.9 to 59.8; CI = 95) for rigid lens wearers, based on a sample of Dutch residents who underwent blepharoptosis surgery. Others who also conducted work in the Netherlands have estimated a much greater odds ratio for rigid lens-associated ptosis of 97.8 (odds ratio of 14.7 for soft lenses).

Interestingly, Fonn and colleagues found a reduction in the palpebral aperture size (PAS) of rigid lens wearers, but no significant difference between the PAS of soft lens and non-lens wearers.12

Often, lens-associated ptosis is attributed to the application of excessive force during lens application and removal, which is believed to damage the levator palpebrae superioris. Other researchers have suggested that the “scissors” method of rigid lens removal, where both lids are pulled laterally, may underlie development of such aponeurotic ptosis.13

Cosmetic concerns aside, if the pupil area is encroached, then any type of ptosis has the potential to interfere with vision and/or the extent of the visual field. Despite general agreement that rigid contact lenses can increase the risk of ptosis, this point is seldom mentioned in patient information leaflets.

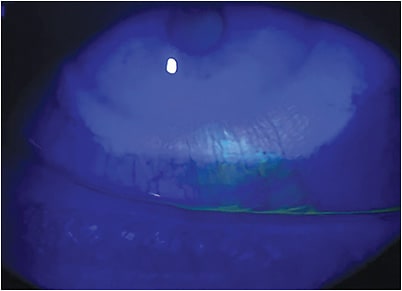

Unwanted Retention of Contact Lenses in the Eye While there have been no large-scale studies of either long- or short-term ocular lens retention, the publication of case reports is common—especially those describing long-term lens retention. Typically, these cases are reported because of the unusually long periods during which the lens has remained undetected in the eye, or some other distinguishing feature considered worthy of discussion (e.g., a recent report linked to unusual orbital anatomy, another relating to the development of conjunctivitis, and in extreme cases the need for surgical intervention to remove a lid cyst or tumor that has developed in response to lens retention).14-25

Of course, most cases may be prevented by regular review, which involves lid eversion and possibly double lid eversion.4 Yet, without any clinical indication to do so, how often would an ECP routinely evert a patient’s eyelids during a sight test? Would someone reporting a vague history of past lens wear provide sufficient impetus to warrant lid eversion? We suspect not, but perhaps the regular trickle of case studies reporting long-term lens retention should encourage practitioners to reconsider how we approach patient lens handling training.

Contact Lens Contamination Risk of infection depends on the interactions between the eye’s natural defense mechanisms (e.g., the ocular surface flora, tear film components, etc.) and the invading pathogen. Various microorganisms reside in and around the ocular adnexa. Usually they pose little threat, but factors such as trauma, immunosuppression, and breach of the ocular surface all hold potential to compromise the defenses and trigger an inflammatory response or infective sequelae.

The introduction of pathogenic organisms—from a contact lens, the lens case, or lens handling—can lead to microbial colonization and increased risk of infection. Given the low incidence of infection, a healthy eye’s own antimicrobial capacity is often sufficient in counteracting pathogenic attacks.

While lens bioburden is one causative factor in contact lens-associated infections, hand-washing is also an essential step in minimizing initial contamination of the lens. Inadequate hand-washing has been estimated to increase the relative risk of contact lens-associated infections by 4.5 times.26

To facilitate removal of contact lenses from the packaging and to mitigate the risk of lens contamination during handling, alternatives to the conventional blister packaging have been proposed. A recently published randomized controlled trial by Tan and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of one such alternative that allows for patients to avoid touching the inner surface of the lens.27

Compared to this alternative design, conventionally packaged lenses with and without ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid had an increased risk of contamination on the inner surface of the contact lens (the part that comes into direct contact with the eye) of 3.38 times and 3.4 times, respectively. The outcomes reflect those of an earlier study in which 3 times lower contamination of lenses was reported for patients using the lenses in the alternative packaging.28

FACILITATING LENS APPLICATION AND REMOVAL

Application and Removal Devices Many products have been marketed to facilitate contact lens application and removal. While the use of some of these devices appears widespread, little research has been conducted to establish their efficacy or potential adverse effects.

Safety and efficacy are generally gauged based upon subjective, rather than the more conventional, rigorous approaches to research. Given the lack of negative reports, it is perhaps safe to assume that such devices present little cause for concern. Nevertheless, the occasional cautionary tale has been shared. In 1976, Kurz described a patient who had inadvertently applied a lens removal device to the cornea in the absence of a contact lens. Apart from pain, there was little other damage.29

Other less orthodox approaches to lens handling have also been proposed; for example, the use of cotton buds fashioned into a pair of tweezers for use in emergency situations and using Minims to create a lens suction device.30,31

Improved understanding of lens removal and application devices, specifically how they may facilitate the initial handling process and prevent dropouts, may enable us to reach a wider patient base. Research should focus on the efficacy and safety profiles of such devices and the changes in bioburden they may introduce.

Topical Anesthetic The use of topical ocular anesthesia during lens fittings may be associated with fewer dropouts, improvements in comfort, and reduced patient anxiety.32 Yet, recent work has questioned the role of lid margin sensitivity in rigid lens tolerance, and it also appears that U.K. practitioners are generally not keen on utilizing anesthesia during lens fittings: fewer than 2% do so on a regular basis.33 In our own experience, some ECPs feel that patients ought to be provided with the “real experience” and not lulled into a false sense of security through the use of anesthesia. Practitioners also sometimes advocate fitting a different lens to each eye to gain an understanding of the wearer’s first impression.

Lens Inversion For soft contact lens wearers, it can be a challenge to ensure that the lens is facing the correct way prior to application. While some practitioners advocate viewing the lens from the sagittal aspect to identify the most “bowl-shaped” side, others suggest pinching the lens to check lens edges for inversion (the “taco” test) (Figure 2).

To facilitate lens handling, some manufacturers have incorporated visibility tints that also can help identification of right and left lenses. For example, rigid lenses may typically include a green or blue tint with the second letter of each color (“R” or “L”) corresponding to right and left lenses. For soft lenses, manufacturers have gone further by adding visibility markings or text onto the lens itself. More recently, there have been innovations in lens packaging to ensure the lens is in the correct position upon initial removal from the pack.

OTHER POINTS FOR CONSIDERATION

Children and Teenagers In a survey of teenagers, more than half identified lens handling as a concern.34 In general, lens application appears to present more difficulty than removal, but overall, the success rates are high.35,36 Training times may be slightly longer (by ~15 minutes) for younger versus older children (8- to 12- versus 13- to 17-year-olds).4,37

Under-Researched Areas Most considerations center around the able-bodied patient. To ensure an inclusive approach, establishing the best way of training individuals who have disabilities or health conditions that affect lens manipulation perhaps ought to be given greater importance. For instance, manual dexterity and other fine motor skills may be negatively impacted by tremors induced by medications or neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, or following a stroke.38 There has also been little investigation into how hand anomalies may influence the decision to wear contact lenses or the impact this may have upon lens handling.

Given the psychological, practical, and visual benefits of contact lens wear that can help make a positive difference to an individual’s life, active recommendation of contact lenses as an eyewear solution should be considered for all suitable patients.

Sources of Information Since the early days of the internet, patients have sought health advice online. Gone is the view of the patient as a passive recipient of health information. How does this relate to contact lens handling?

Yildez and colleagues report that while useful online contact lens video resources exist, poorer quality videos with insufficient information tend to dominate.39 Thus, redirecting patients to more reliable sources may be beneficial, but to where exactly? In the absence of hard evidence, perhaps the best that practitioners can hope for is an approach to lens application/removal that is safe, not necessarily one that will prevent dropouts.

CONCLUSION

Lens handling is a cornerstone of successful lens wear, but not an area that has benefited from significant research.

Of course, there are aspects of lens handling that may be more difficult to modify (e.g., an aversion to touching the eye), but investing in research and optimizing the process of application and removal could have an impact on dropout rates. Better training approaches could also positively impact quality of life and vision in patients who desire to wear contact lenses but have been dissuaded by unsuccessful attempts at lens handling.

ECPs should also consider how they approach lens handling in the digital world and how to use practices that best suit their patients’ learning preferences. CLS

References

- Sulley A, Young G, Hunt C, McCready S, Targett MT, Craven R. Retention Rates in New Contact Lens Wearers. Eye Contact Lens. 2018 Sep;44 Suppl 1:S273-S282.

- Sulley A, Young G, Hunt C. Factors in the success of new contact lens wearers. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2017 Feb;40:15-24.

- Jones L, Walsh K, Willcox M, Morgan P, Nichols J. The COVID-19 pandemic: Important considerations for contact lens practitioners. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Jun;43:196-203.

- Wolffsohn JS, Dumbleton K, Huntjens B, et al. CLEAR - Evidence-based contact lens practice. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2021 Apr;44:368-397.

- Macedo-de-Araújo RJ, van der Worp E, González-Méijome JM. A one-year prospective study on scleral lens wear success. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020 Dec;43:553-561.

- van den Bosch WA, Lemij HG. Blepharoptosis induced by prolonged hard contact lens wear. Ophthalmology. 1992 Dec;99:1759-1765.

- Reddy AK, Foroozan R, Arat YO, Edmond JC, Yen MT. Ptosis in young soft contact lens wearers. Ophthalmology. 2007 Dec;114:2370.

- Hwang K, Kim JH. The Risk of Blepharoptosis in Contact Lens Wearers. J Craniofac Surg. 2015 Jul;26:e373-e374.

- Watanabe A, Imai K, Kinoshita S. Impact of high myopia and duration of hard contact lens wear on the progression of ptosis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2013 Mar;57:206-210.

- Kersten RC, de Conciliis C, Kulwin DR. Acquired ptosis in the young and middle-aged adult population. Ophthalmology. 1995 Jun;102:924-928.

- Verhoekx JSN, Detiger SE, Muizebelt G, Wubbels RJ, Paridaens D. Soft contact lens induced blepharoptosis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019 Feb;97:e141-e142.

- Fonn D, Holden BA. Extended wear of hard gas permeable contact lenses can induce ptosis. CLAO J. 1986 Apr-Jun;12:93-94.

- Thean JH, McNab AA. Blepharoptosis in RGP and PMMA hard contact lens wearers. Clin Exp Optom. 2004 Jan;87:11-14.

- Kao CS, Shih YF, Ko LS. Embedded hard contact lens: reports of a case. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990 Mar;89:234-236.

- Brinkley JR Jr, Zappia RJ. An eyelid tumor caused by a migrated hard contact lens. Ophthalmic Surg. 1980 Mar;11:200-202.

- Burns JA, Cahill KV. Long-term dislocation of a hard contact lens. Ophthalmic Surg. 1986 Aug;17:493-495.

- Benger RS, Frueh BR. An upper eyelid cyst from migration of a hard corneal contact lens. Ophthalmic Surg. 1986 May;17:292-294.

- Ho DK, Mathews JP. Folded bandage contact lens retention in a patient with bilateral dry eye symptoms: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017 Jul 4;17:116.

- Agarwal PK, Ahmed TY, Diaper CJ. Retained soft contact lens masquerading as a chalazion: a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013 Feb;61:80-81.

- Zola E, van der Meulen IJ, Lapid-Gortzak R, van Vliet JM, Nieuwendaal CP. A conjunctival mass in the deep superior fornix after a long retained hard contact lens in a patient with keloids. Cornea. 2008 Dec;27:1204-1206.

- Richter S, Sherman J, Horn D, Zelaznick S. An embedded contact lens in the upper lid masquerading as a mass. J Am Optom Assoc. 1979 Mar;50:372-373.

- Holicki C, Sims J, Holicki J. Two Soft Contact Lenses Retained in the Superior Fornix for 15 Years in a Patient With Unique Orbital Anatomy. Eye Contact Lens. 2020 Mar;46:e13-e16.

- Bock RH. The upper fornix trap. Br J Ophthalmol. 1971 Nov;55:784-785.

- Arshad JI, Saud A, White DE, Afshari NA, Sayegh RR. Chronic Conjunctivitis From a Retained Contact Lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2020 Jan;46:e1-e4.

- Patel S, Tan LL, Murgatroyd H. Unexpected cause for eyelid swelling and ptosis: rigid gas permeable contact lens migration following a 28-year-old trauma. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Aug 10;2018:bcr2018225767.

- Efron N, Morgan PB. Rethinking contact lens aftercare. Clin Exp Optom. 2017 Sep;100:411-431.

- Tan J, Siddireddy JS, Wong K, Shen Q, Vijay AK, Stapleton F. Factors Affecting Microbial Contamination on the Back Surface of Worn Soft Contact Lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 2021 May 1;98:512-517.

- Nomachi M, Sakanishi K, Ichijima H, Cavanagh HD. Evaluation of diminished microbial contamination in handling of a novel daily disposable flat pack contact lens. Eye Contact Lens. 2013 May;39:234-238.

- Kurz GH. Contact lens remover adherent to cornea. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976 Aug;82:317-318.

- Stockdale J, El-Shammaa E. Contact lens removal: the “chopstick” approach. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Jul;28:707-708.

- Ahmad R, Manjunatha NP, Nag P, Desai SP. Insertion of a bandage contact lens with Minims. Eye Contact Lens. 2007 Mar;33:89-90.

- Gill FR, Murphy PJ, Purslow C. Topical anaesthetic use prior to rigid gas permeable contact lens fitting. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2017 Dec;40:424-431.

- Gill FR, Murphy PJ, Purslow C. A survey of UK practitioner attitudes to the fitting of rigid gas permeable lenses. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2010 Nov;30:731-739.

- Zeri F, Durban JJ, Hidalgo F, Gispets J; Contact Lens Evolution Study Group (CLESG). Attitudes towards contact lenses: a comparative study of teenagers and their parents. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010 Jun;33:119-123.

- Plowright AJ, Maldonado-Codina C, Howarth GF, Kern J, Morgan PB. Daily disposable contact lenses versus spectacles in teenagers. Optom Vis Sci. 2015 Jan;92:44-52.

- Soni PS, Horner DG, Jimenez L, Ross J, Rounds J. Will young children comply and follow instructions to successfully wear soft contact lenses? CLAO J. 1995 Apr;21:86-92.

- Walline JJ, Jones LA, Rah MJ, et al. Contact Lenses in Pediatrics (CLIP) Study: chair time and ocular health. Optom Vis Sci. 2007 Sep;84:896-902.

- Bhidayasiri R. Differential diagnosis of common tremor syndromes. Postgrad Med J. 2005 Dec;81:756-762.

- Yildiz MB, Yildiz E, Balci S, Özçelik Köse A. Evaluation of the Quality, Reliability, and Educational Content of YouTube Videos as an Information Source for Soft Contact Lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2021 Nov 1;47:617-621.