With any niche service, technique and skill evolve with time and experience, and orthokeratology (ortho-k) is no different. As I’ve taught student interns and optometry residents over the years, the development of their ortho-k assessment skills resembles a growth pattern similar to my own. Hopefully, the following tips can help other new ortho-k enthusiasts also advance their skills.

When I first started fitting scleral lenses, the goal was to vault the lens over the cornea and limbus and then land the lens on the sclera. There was no specified tear reservoir depth or focus on toric peripheral curves. The approach of new ortho-k prescribers is somewhat similar in that the primary focus of the assessment is the presence of a center bullseye with sodium fluorescein (NaFl). If that is observed, the rest of the fit falls to the wayside.

Start by shifting focus away from the center bullseye to the dark areas of the NaFl pattern. The outermost dark ring is the alignment zone, and creating a lens that is well-aligned to the corneal surface facilitates an effective ortho-k lens. Think of the alignment zone like the landing curves of a scleral lens. Sometimes you can get away with a spherical landing, but you often need toric or even quadrant-specific curves to achieve desired fit.

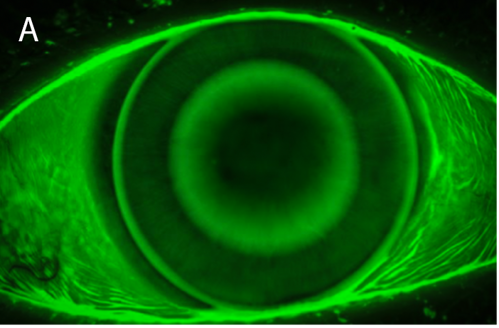

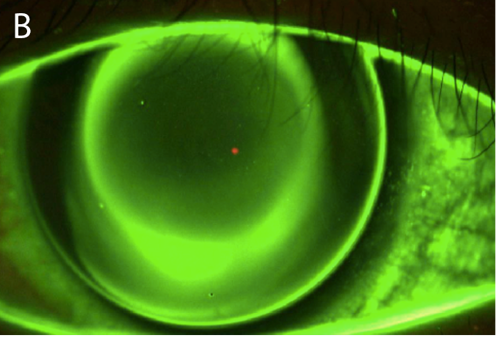

Evaluate the images below: The first has an even alignment zone 360° around the center bullseye (see Figure 1a), whereas the second image shows NaFl bleeding into the inferior quadrant of the alignment zone (see Figure 1b). The lack of a defined bullseye due to a poor fitting alignment curve can negatively impact the forces that encourage epithelial migration that happens under an ortho-k lens, leading to decreased acuity. Like a scleral lens with edge lift, adding toric or quadrant-custom peripheral curves can improve the outcome of this fitting process.

As scleral and ortho-k lenses with loose edges can be problematic, so can those with tight-fitting relationships. Ortho-k lenses with alignment curves that are fit too steep to the peripheral cornea can create lens binding that leads to peripheral corneal staining and ocular discomfort.

Gaining confidence on the central lens–cornea relationship and understanding how that should look at dispense and follow-up visits can also take some time to master. The dark central area of an ortho-k fit should appear defined, but the borders of the surrounding NaFl bullseye will show some tear movement or exchange over the central cornea as the lens moves slightly on blink.

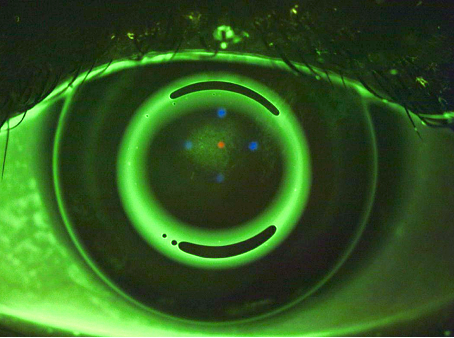

An ortho-k lens that is too shallow will resist exchanging the tear layer over the central cornea and cause central epithelial breakdown, as noted in Figure 2. A shallow lens may also show excessive edge lift, as the lens is bearing primarily on the central cornea. When edge lift is present, it is important to identify if it is because the lens is too shallow, or if the edges are too flat.

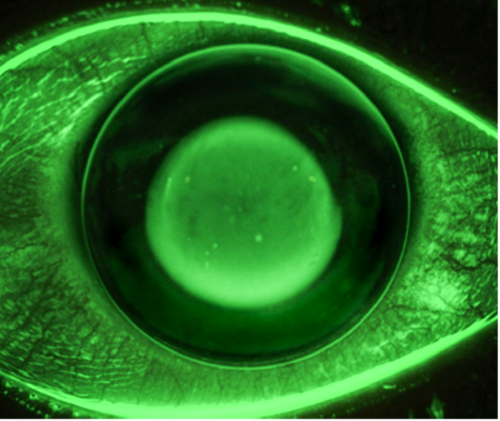

A lens that is too deep will show excess NaFl over the central cornea and is associated with a central island on topography. These patients will require more minus power in their manifest refraction than anticipated, and while it seems logical to flatten the base curve to correct the residual myopia, the correct remedy is to reduce sagittal depth to properly influence the epithelium. Deep lenses may also lack tear exchange or show minimal edge lift, as seen in Figure 3.

To a new fitter, the bright center bullseye may be the most intriguing part of an ortho-k fit. However, achieving a great outcome is done through the arguably less flashy peripheral alignment curves to promote stable and predictable outcomes.

Images courtesy of Brooke Messer

This editorial content was supported via unrestricted sponsorship